By Charlie Beckett, Director of Polis, LSE

Fake News has upset a lot of people and caused real damage but it’s been good news for journalism analysts like me. I’ve never had more interest in a media issue than this. I’ve never been busier talking and researching a topic and it’s consequences. Here are some notes that I use when I give talks about fake news. This article by Charlie Beckett, Polis, LSE @CharlieBeckett

You may be sick of hearing the phrase but that is part of the problem.

This is one of the most important information issues of our time.

This is not just because of those Macedonia teenagers peddling lies. Not just because of extremist political factions seeking to wreck liberal democracy.

Not even just because we have presidents in Russia and America who seek to profit politically and personally from encouraging a cynical, disruptive nihilism and who throw the term around like rhetorical grenades.

Fake news is the canary in the digital coal mine. It is a symptom of a much wider systemic challenge around the value and credibility of information and the way that we – socially, politically, economically – are going to handle the threats and opportunities of new communication technologies.

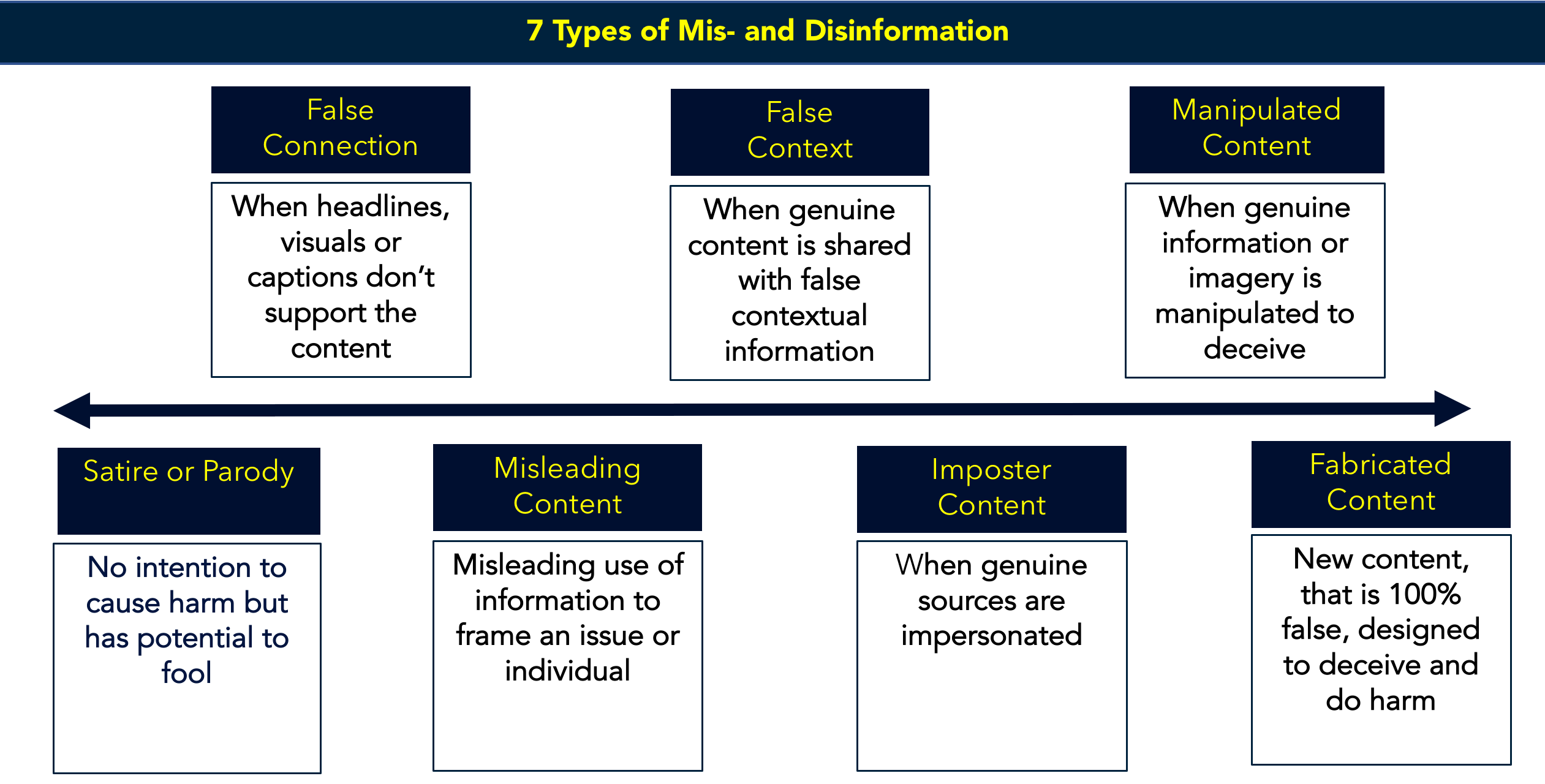

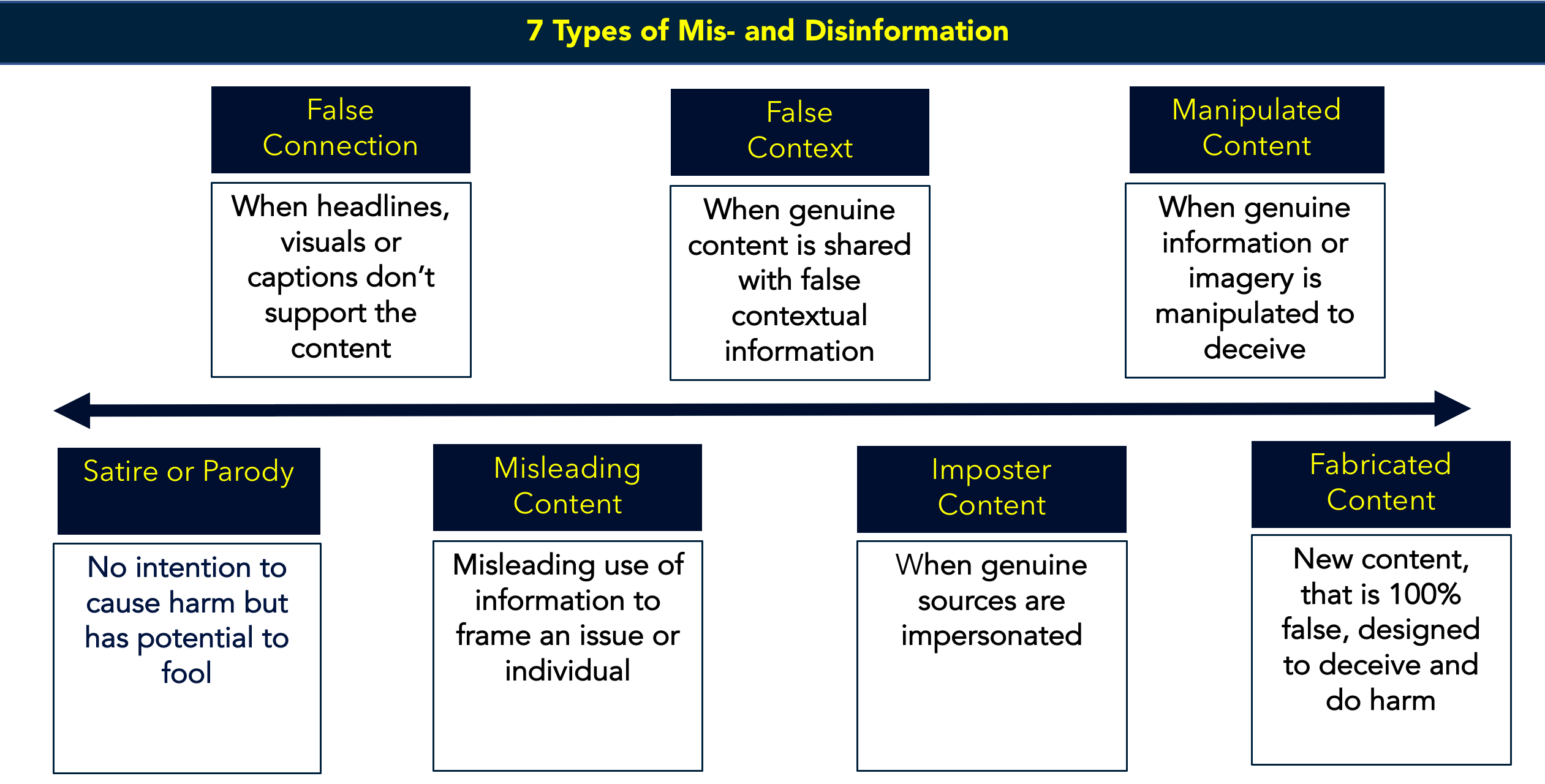

Firstly, let’s recognise that ‘fake news’ is actually a range of misinformation as described in this graphic by First Draft News, the verification agency:

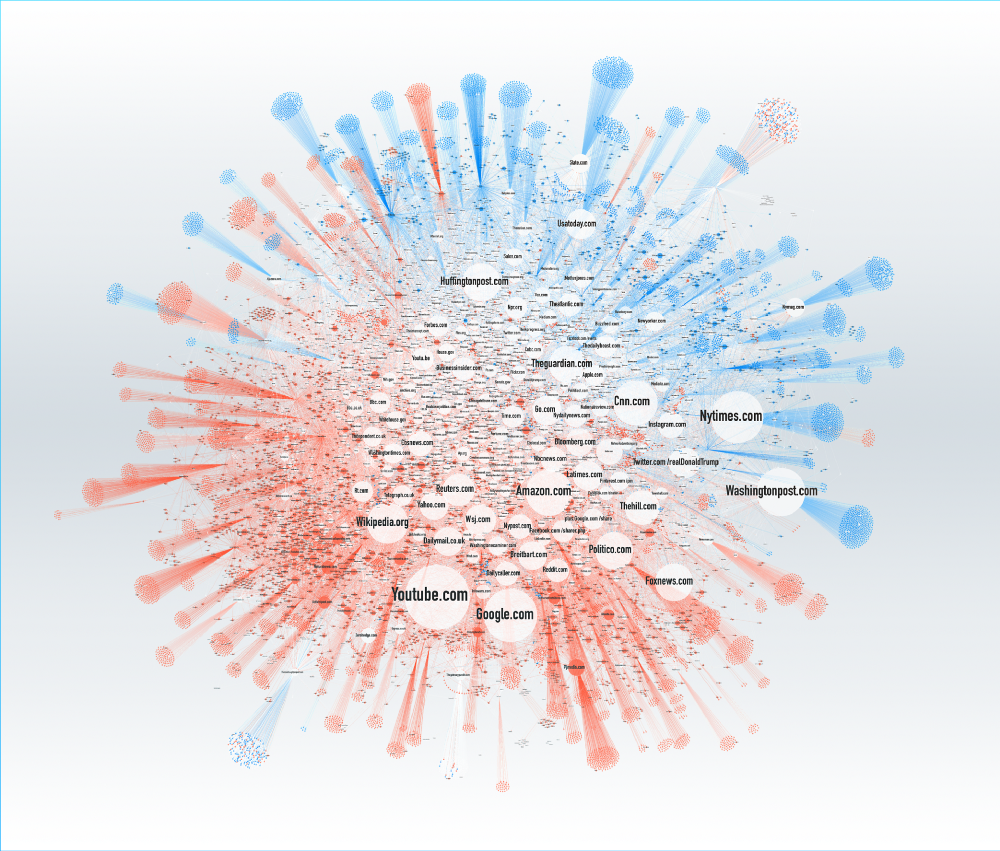

Let’s also accept that it may not have decided the US election. I suspect it was marginal but a significant dynamic in shifting the agenda and mobilising support for Donald Trump. So it is a real media factor and indicative of a wider shift towards a more decentralised media ecology where insurgent sources can have more impact than in the past. Jonathan Albright’s analysis of ‘fake news’ shows that it is highly adept at exploiting digital networks from Facebook to email fuelled by technology like bots that accelerate its spread.

This is a technological problem. It requires us also to think realistically about how people understand and share information in the digital age: feelings are as important as facts. Identity is as much a motivation as integrity. These are not necessarily ‘bad’ things. But they are not how mainstream news media and politicians used to think about information.

This is a technological problem. It requires us also to think realistically about how people understand and share information in the digital age: feelings are as important as facts. Identity is as much a motivation as integrity. These are not necessarily ‘bad’ things. But they are not how mainstream news media and politicians used to think about information.

As I’ve written elsewhere, there is a commercial and technological context to fake news, but ultimately it is a political issue. We have to understand ideologies of information. For anyone dealing in information, ethics is now not an add on. It is integral to the information economy. Trust is the currency of networked media. Around fake news we have a remarkable opportunity to get it right.

Firstly, we have to get this in perspective. I think a lot of the reaction to ‘fake news’ has been a moral panic. Much of what we – and Trump – calls fake news or post truth or filter bubbles – is simply what we disagree with or feel threatened by. I’m not sure we’d be having this debate amongst ‘liberal elites’ if Hillary had become president and the UK had voted to Remain.

In the UK, fake news has had less purchase. Possibly because we already have a partisan media and our public is used to journalists, politicians and other communicators bending the truth to suit agendas. That’s not a bad thing if its transparent. Opening up news media to more diverse perspectives and sources allows for a more robust, diverse debate where the public has more say.

But the best debates that produce the most sustainable policy outcomes must at some point return to reality. Democracy needs evidence for accountability. There may not be a single truth, but there are such things as facts.

If we get to a situation – which we are close to – where everything is relative, where no-one accepts the terms of a debate – where expertise and emotional engagement are distrusted. Then we all stand to lose.

Information, data, discourse – online, on demand, personalised, distributed, ‘disintermediated’- is now the medium, the environment for social and economic life. If it is polluted then anyone seeking credibility stands to lose. Look at what has happened to companies like Uber or Facebook recently. They are extraordinary services but they did not align their actions and strategy with a credible ethical framework. They were also – to varying degrees – fake.

In my sector of journalism, fake news is the best thing that has happened for decades.

It gives mainstream quality journalism the opportunity to show that it has value based on expertise, ethics, engagement and experience.

It is a wake up call to be more transparent, relevant, and to add value to people’s lives.

It can develop a new business model of fact checking, myth busting and generally getting its act together as a better alternative to fakery.

One of the positive effects that ‘fake news’ has had is to provoke debate but also action. We can see networks taking action to separate advertising from fake content. We see a boom in fact-checking. Tools and policies are being designed to help the user to assess the quality of information. There is a renewed interest in developing media or news ‘literacy’.

But as we get stuck into the practical and political task that ‘fake news’ has set, here are some more ethical, strategic ideas for how different sectors of the information world might approach the challenge>

Journalists should:

- Connect – be accessible and present on all platforms

- Curate – help users to good content where ever it is

- Be relevant – use users’ language and listen creatively with data

- Be expert – add value, insight, experience, context

- Be truthful – fact checking, balance, accuracy

- Be human – show empathy, diversity, constructive

- Transparency – show sources, be accountable, allow criticism

The networks and other organizations that distribute news:

- Filter out fake news better

- Give the user better signals of the quality of content

- Promote better content through algorithms

- Promote news literacy

- Ensure more resource and reward goes to credible producers and publishers

Other authorities (government, business, education) should:

- Communicate where the public communicate

- Talk the right languages: conversational, human, even humorous

- Be relevant

- Open up

- Be interactive

- Be realistic – media has limited influence

That last point is important. Media is not the world and it is as much a reflection as a cause of social, economic or political problems.

Regulation won’t solve this. Media literacy won’t solve this.

This is a long-term incremental problem.

It’s an age old problem, that of the ideal of the informed public.

It’s not solvable – but it’s treatable. And Any investment in this will add value to communications as an industry and to society.

By Charlie Beckett, Director of Polis, LSE