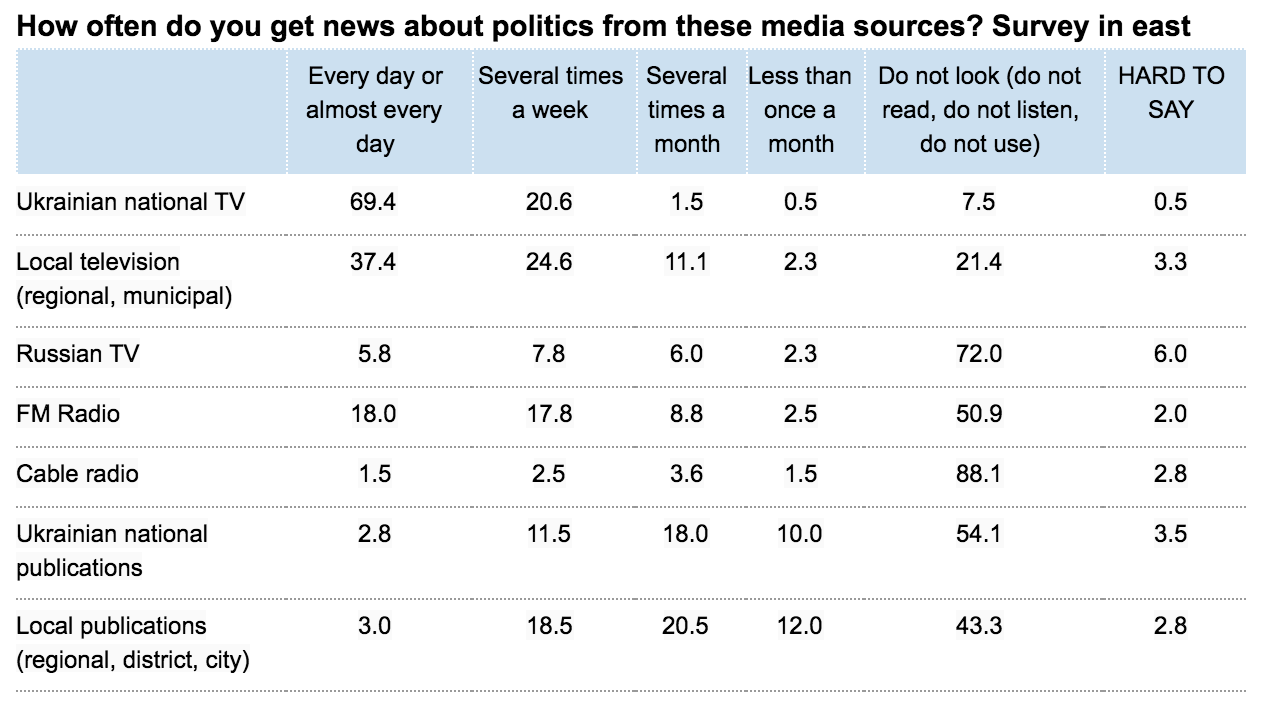

Less than six percent of residents in unoccupied eastern Ukraine watch programs about politics on Russian television every day, a new study by the Kyiv International Institute of Sociology finds, Alexandra Markovich wrote for Kyiv Post.

The study, which was conducted from May 20 to June 2, 2016, found that Ukrainian national television channels were the dominant source of political news in eastern Ukrainian, as well as throughout the country.

The study upends widely held assumptions about the singular dominance of Russian television in eastern Ukrainian households.

“This is a stereotype that does not reflect reality,” said Anton Grushetsky, Head of the Quantitative Surveys Department at the Kyiv International Institute of Sociology, referring to the common assumption that most people in eastern Ukraine watch Russian television.

According to the study, 72 percent of residents in the unoccupied east do not “get information of a political nature” from Russian television at all. Less than six percent watch Russian television nearly every day for news about politics, 7.8 percent watch it several times a week, and six percent watch it several times a month.

Still, residents in eastern Ukraine got political content from Russian television more often than people in the rest of the country. Twenty percent of people in eastern Ukraine watched political content on Russian television at least once a month, compared to 16 percent in the country as a whole, and 7.8 percent in the west.

The survey was conducted only in the parts of the east that the Ukrainian authorities control. Grushetsky said he expects the numbers would have been higher had the occupied parts of eastern Ukraine been included in the survey.

“The percentage of those watching Russian television in the occupied territories is greater, but we don’t know how much greater,” he said. Grushetsky said about half of eastern Ukraine was surveyed.

Few trusted Russian television, even in the eastern regions surveyed. Nine percent of people in unoccupied eastern Ukraine fully trust or trust, rather than distrust political news from Russian television, compared to fifty percent for Ukrainian national TV channels.

Two-fifths of respondents watched local television everyday. Grushetsky said he did not know whether those television stations were controlled by Russian or Ukrainian media, or operated independently.

In May, Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko signed a decree banning several Russian journalists and media executives from Ukraine in what he said was an effort to fight against Russian propaganda in the country. The survey casts some doubt the apparent prevalence of Russian propaganda, though with reservations.

An editor’s note introducing the survey, which was published on June 9, commented on the increasing difficulty of conducting sociological work in both the government controlled and occupied parts of Luhansk and Donetsk. The note cited as a particular challenge the lack of reliable information about how many people live in the regions.

Though not as many people in eastern Ukraine watch Russian television as expected, the ones that do are particularly susceptible to Russian propaganda, another Kyiv International Institute of Sociology study found in February 2015.

By Alexandra Markovich, Kyiv Post

Alexandra Markovich covers politics for the Kyiv Post. She has freelanced higher education news for The New York Times and The Washington Post