By Lóránt Győri, Péter Krekó, for The Riga Conference

While a lot of attention has been dedicated to the relationship between Moscow and the far-right parties in Europe,[1] this paper aims to shed some light on the opposite side of the political spectrum. Despite increasingly promoting conservatism, traditionalism, and family values,[2] and defining Russia as a global “moral compass” built on those values,[3] the Putin regime seem to reboot the red “comrade networks” as well, inherited from the USSR and used extensively for active measures.

The radical left-Russia connection: gaining momentum

“We will do everything to restore power and strengthen Soviet power everywhere on the territory of our former motherland”. These were the sentences of the Communist party leader, Gennady Zyuganov, on a party rally before the parliamentary elections in Russia this September[4]. The party finally won the second most votes after the United Russia party of Putin and Medvedev, with 14% of the votes. While the party lost some support since the last parliamentary election back to 2011 (when they gained 19%), the Communist party definitely remained an important political player in Russia, serving as an extended left hand of the Kremlin in its geopolitical expansion.

The Communists (like all the other parliamentary parties in Russia) are only pet opposition parties that follow the Kremlin line on every crucial issue. They, for example, participated in the fake electoral monitoring missions in Crimea and Eastern Ukraine to legitimize the Kremlin’s military intervention. [5] Furthermore, in some questions they are even more radical than United Russia. They have a post-Soviet nostalgia, and consequently, an expansionist agenda on the post-Soviet sphere of influence. They have an outreach to Communist Parties all over the World. In times, when Putin is talking about the “breakup of the USSR was the biggest tragedy of the 20th century”,[6] he asserts that he “likes the ideas of communism very much”;[7] and Stalin-busts and Stalin Museums are erected;[8] they are safely representing the state-defined mainstream.

On the other hand, the radical left is on the rise in Europe. The 2008 financial crisis and the austerity measures helped the resurgence of radical left forces on the continent to a similar significant extent to that of far-right parties. In the European Parliament, the radical left GUE-NGL’s ratio rose from 4,6% of MEPs in 2009, to 6,9% in 2014. In national elections, far-left parties were able to increase their share of votes to 150% of their pre-crisis levels.[9] And while the meteoric far-left rises such as those of Syriza (Greece) and Podemos (Spain) are rare, they have important political positions in Europe. Syriza is the main governmental force in Greece; and with its right-wing populist coalition partner ANEL, it works to ally itself with Russia on energy, foreign affairs and defence. Die Linke is strong in eastern Germany, present in regional governments and has a regional PM in Thuringia. Cyprus’ communist AKEL party gained more than 30% of the vote in the last parliamentary election and used to be on government. Sinn Fein is currently the third most popular party in Ireland and has been an important player on the political scene for decades.

The Communist Party has a friendly relationship with the official club of the radical left parties, The Party of the European Left. The danger of the alliance between far-left parties and the Kremlin (mediated by the Communists) arises from multiple crises in Europe which give populist players, as well as Moscow a good opportunity to challenge the European mainstream, and it institutions.[10]

Resurrecting the historical relations: Crimea and the “self-independence”

The 1990s were marked by a weakening of the ties between Moscow and its former “comrades,” but after 2000 the Putin regime gradually looked to re-establish some of the pre-existing connections with the “new” socialist left in Europe and beyond. While Russia, for historical reasons, has many strong ties with Communist parties in Europe, this relationship did not gain any importance before the geopolitical tensions raised in Europe: in the Georgian-Russian conflict, and even more importantly, the Ukranian conflict, and Crimea more particular.

The Maidan events have been painted by several radical left parties in the taste of the Kremlin: a “Fascist coup in Kiev”. And not only by the good old Communist forces, but also by the representatives of the most prominent forces of the “new left” such as Syriza and Podemos. The dominant narrative was that there is a fascist takeover going on in Ukraine, and extreme right forces are hanging around to terrorize the Russian minority. In addition, some radical left players went far beyond then words to help for the pro-Russian separatists. The German Die Linke and the Communist Party of Greece (KKE) for example, delegated “independent observers” to the (internationally unrecognised) referendum on Crimean independence, alongside their alleged political opponents – observers from European far-right parties such as the Front National from France, Jobbik from Hungary, and FPÖ from Austria.[11] It all happened in the name of the fight against anti-fascism and autonomy. The latest chapter of such legitimation rituals includes the “Donetsk People’s Republic” and “Luhansk People’s Republic” parliamentary election monitored by the Communist Party of Greece in late 2014; die Linke delivering “humanitarian help” to the “Donetsk People’s Republic” (DNR) in 2015, and finally Andreas Maurer from die Linke recognizing Crimea as part of Russia.[12]

In the name of “Peace” – defending Russian interests all over Europe

However, Russia’s influence via far-left parties extends far-beyond Crimea and Eastern Ukraine. The European radical left played a very prominent role in the overall legitimisation of Russia’s policies in the European Parliament.

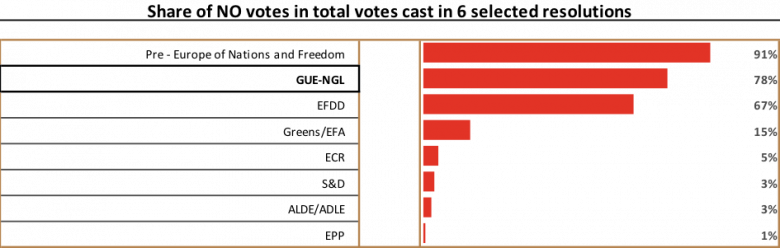

Despite expressions of solidarity with Ukraine and denouncing Russian military aggression,[13] the GUE/NGL parliamentary group consistently pursued a pro-Kremlin line in the European Parliament throughout 2014-2015. It voted against every important resolution aimed at keeping the Kremlin at bay in 78 percent of the cases (see Figure 1 below).[14]

Figure 1. Share of “no” votes of EP groups in selected resolutions criticizing the Russian government in the European Parliament

Source: PCI calculations based on votewatch.eu[15]

The GUE/NGL went against even its own declared pacifism by unanimously rejecting the Parliament’s resolution calling for a military de-escalation in Syria on the eve of the Russian intervention.[16] Therefore, it is not a surprise that GUE/NGL MEPs called for the lifting of sanctions against Russia during an October 2015 visit to Moscow,[17] and condemned Jean-Claude Juncker’s call for a European army for “further escalating the situation in eastern Ukraine.”[18] Finally, the faction’s June 2016 conference titled “Peace and ANTI – NATO” bashed the military organization for posing a nuclear threat to Russia and the Middle East.[19]

Communist networks reach much beyond Europe, mainly via the Communist Party, and the worldwide International Meeting of Communist and Workers’ Parties, a sort of “post-Communist International” which serves as a worldwide power projection for the Kremlin. The joint statement of the 16th conference in Ecuador denounced the Western “imperialist intervention in Ukraine,”[20] while the 17th conference statement praised Assad as the force defending Syria from Western imperialism. The reason for this is that the radical left often portrays the Russian and Syrian regimes and Eastern Ukrainian rebels as victims of a Western aggression. [21]

Three shades of Putinism

The far-left’s pro-Putinism is less open, less direct and less ideological than of the far-right’s. Some individual parties are sometimes quite shy of their pro-Kremlin stance, while some others are very open about it. We differentiate between three different forms of pro-Putinism here.

The ones who “rally around the Russian flag” are openly supporting Moscow. A handful of far-left parties can be characterized as such like the KKE or die Linke. Founder of the French Left Party, Jean-Luc Mélenchon said in the EP that “The Crimean ports are vital for the security of Russia, (…) they are taking measures to protect themselves against an adventurer (…) on whom neo-Nazi influence is quite detestable. […] The Russian nation cannot allow North Americans and NATO moving closer to their doors.”[22]

Other, more reserved radical left forces suffer from “hemispatial neglect”: they remain totally silent on the war crimes of Russia and Assad’s regime in Syria, only criticizing the West for human rights abuses. The joint statement of the Communist Parties of Greece and Turkey stated for example, “The imperialist intervention of the USA, NATO, EU, Turkey, Israel and the Gulf monarchies in Syria that has been going on for 5 years and has led to the deaths of hundreds of thousands of people”. [23] However, they did not find any problem in that Russia-supported Assad is killing hundreds of thousands of civilians in Syria.

A few far-left parties express a “balancing” approach in line with their ideology of denouncing both Western and Russian imperialism – like Luxembourg-based Left Party and the Sinn Fein. This position, criticizing the West and Russia at the same time, has its inherent problems as well: it denies for example that the role of Russia, with its direct military intervention, was incomparably greater in contributing to the Ukranian crisis than that of the West.

Geopolitical dangers and possible solutions[24]

Radical left political forces show more loyalty towards Russia than the West on defence fields. The radical left-nationalist Greek government, one of the biggest friends of Moscow, has for example announced their intention to set up joint manufacturing of Kalashnikov by Russia and Greece, projecting the termination of the sanctions. Before the last NATO summit, Die Linke was calling for abolishing the military organisation, and creating a new military organization including Russia, and countries “from Lisbon to Vladivostok” instead.

While they cannot cause a huge trouble, they can contribute to undermining the legitimacy of the NATO. What can be done to counter such a danger:

More integrated intelligence services in the EU under the European Council or the European Commission would be an efficient tool to reveal the links between radical left players and Moscow (used for active measures in the past, and possibly used today as well). It would be especially important given the reluctance of some member states to reveal these links being afraid of deteriorating their economic and political relations with Russia.

On the political level, it would be important to highlight the pro-Russian connections of radical left parties, and destroy the credibility of such parties in political debates. It is difficult to understand why radical left parties that profess secular, egalitarian and pacifist politics admire Russia’s “post-communist neoconservative” system, which shows strong authoritarian and chauvinist tendencies, emphasises the role of religion, reproduces and strengthens mass inequalities, promotes an aggressive nationalist-imperialist geopolitical agenda and repeatedly threatens the West with nuclear weapons. The core values of the Russian regime, often mentioned as the nation, the family and Christianity, are rarely guiding values for left-wing parties. Given that the radical left is mainly posing a threat to the voter base of the green and social democrat parties they would have a vested interest in challenging the radical left’s contradictory pro-Russian stance that is completely ignoring the anti-egalitarianism, imperialism, and ultra-conservatism of the Putin regime. Unfortunately, social democrats are traditionally rather reluctant to talk about Russian influence; they call for “pragmatic” relations instead.

If the loyalties of some European radical left parties towards Russia remains a non-topic in political discourses, the rise of these parties can be even more spectacular in the future. What we observe in Greece, Spain, and even Germany — the radical left taking away votes of mainstream social democratic parties — can become an even more massive trend in Europe. And it could definitely undermine Euro-Atlantic relations.

[1] http://www.riskandforecast.com/useruploads/files/pc_flash_report_russian_connection.pdf, http://www.politicalcapital.hu/2015/12/az-europai-szelsojobboldal-kapcsolata-a-kremllel-the-kremlin-connections-of-the-european-far-right/

[12] http://anton-shekhovtsov.blogspot.hu/2014/11/fake-monitors-observe-fake-elections-in.html, http://anton-shekhovtsov.blogspot.hu/2015/02/german-die-linke-delegation-visits.html, http://www.stopfake.org/en/fake-german-town-of-quakenbruck-to-recognize-crimea-as-part-of-russia/

[15] 1 – Strategic military situation in the Black Sea Basin following the illegal annexation of Crimea by Russia (11.06.2015), subject (vote: resolution), type of vote (motion for a resolution), http://www.votewatch.eu/en/term8-strategic-military-situation-in-the-black-sea-basin-following-the-illegal-annexation-of-crimea-by-ru-15.html

2 – State of EU-Russia relations (10.06.2015), subject (vote: resolution), type of vote (motion for a resolution), http://www.votewatch.eu/en/term8-state-of-eu-russia-relations-motion-for-resolution-vote-resolution.html

3 – Murder of the Russian opposition leader Boris Nemtsov and the state of democracy in Russia (12.03.2015), subject (Paragraph 19, amendment 1), type of vote (joint motion for a resolution), http://www.votewatch.eu/en/term8-murder-of-the-russian-opposition-leader-boris-nemtsov-and-the-state-of-democracy-in-russia-joint-mot.html

4 – Macro-financial assistance to Ukraine (25.03.2015), subject (vote: legislative resolution), type of vote (draft legislative resolution), http://www.votewatch.eu/en/term8-macro-financial-assistance-to-ukraine-draft-legislative-resolution-vote-legislative-resolution-ordin.html

5 – EU-Ukraine association agreement, with the exception of the treatment of third country nationals legally employed as workers in the territory of the other party (16.09.2014), subject (approbation), type of vote (draft legislative resolution), , http://www.votewatch.eu/en/term8-eu-ukraine-association-agreement-with-the-exception-of-the-treatment-of-third-country-nationals-lega.html

6 – Situation in Ukraine (17.07.2014), subject (vote: resolution), type of vote (joint motions for a resolution), http://www.votewatch.eu/en/term8-situation-in-ukraine-joint-motions-for-a-resolution-vote-resolution.html

[16] Security challenges in the Middle East and North Africa and prospects for political stability (7.09.2015), http://www.votewatch.eu/en/term8-security-challenges-in-the-middle-east-and-north-africa-and-prospects-for-political-stability-motion-6.html#/##vote-tabs-list-2

[19] https://www.akel.org.cy/en/2016/06/06/european-and-international-nato-bases-and-the-threat-of-nuclear-weapons/#.V9u1_ph96M8

[24] These parts are from this article: https://www.opendemocracy.net/od-russia/peter-kreko-lorant-gyori/don-t-ignore-left-connections-between-europe-s-radical-left-and-ru

By Lóránt Győri, Péter Krekó, for The Riga Conference

Lóránt Győri is a sociologist and political analyst

Péter Krekó is a senior affiliate to Political Capital Institute, and a Visiting Fulbright Professor at the Indiana University Central Eurasian Studies Department