By Maiquel Rosauro, for Lupa

Read the Portuguese version of this feature.

The first part of the report: The “truth war”: how Russia created its own ‘fact-checking’ network

“In Russia, we have a saying: Truth is strength. Whoever has the truth is the strongest.” The author of the phrase is Timofey V, head of the Department of Strategic Directions at ANO Dialog, a state center that publicly presents itself as a digital dialogue operator between the Kremlin and the general public.

The statement was made as a way to try to legitimize this year’s elections in Venezuela using a new weapon of the Russian government: state “fact-checking.”

On July 30, in the Venezuelan capital, Caracas, Timofey V took part in the international forum of the Global South journalists’ association “Voices of the New World.” Three days earlier, Venezuela had held municipal elections marked by an opposition boycott.

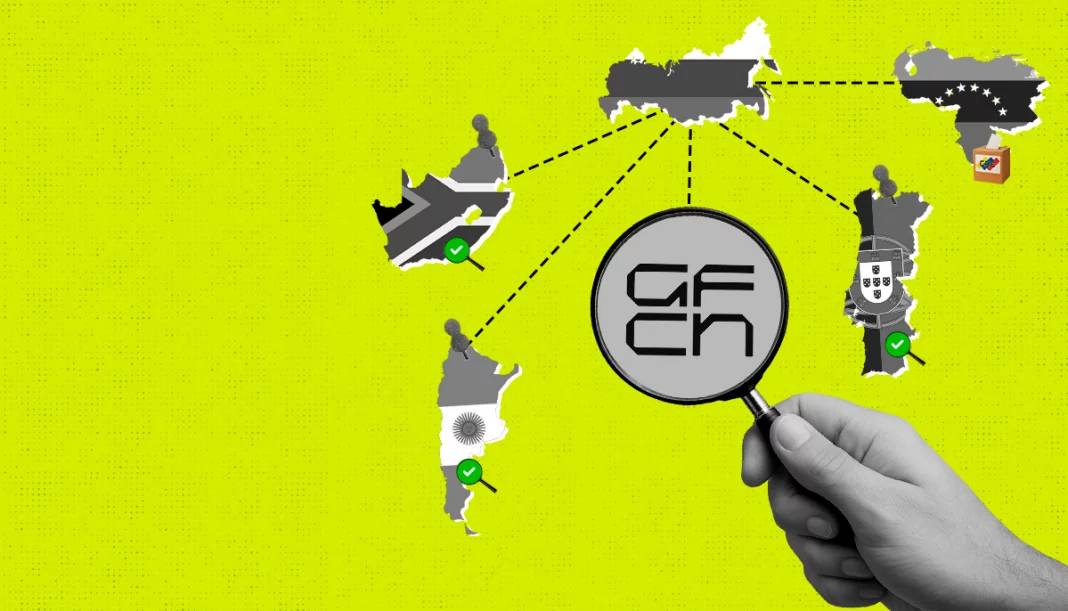

Timofey V’s presence in the country was not only to attend the event, but also to put into practice the first on-site action by the Global Fact-Checking Network (GFCN), a Russian initiative that in practice seeks to counter Western fact-checking but whose methods are not very transparent.

At least three “fact-checkers” from the entity—Alexandre Guerreiro (Portugal), Christian Lamesa (Argentina), and Mantula Nonkululeko (South Africa)—traveled to Venezuela to act as observers in the country’s municipal elections held on the 27th. Their presence led to the publication of four articles in a row on the GFCN website between July 29 and 31. It was the first time an event received both dedicated coverage and a series of posts on the platform’s site.

The election itself, in turn, was criticized by media outlets around the world—including in Brazil, Argentina, and France—for the absence of opposition, low voter turnout and, above all, the perpetuation of a power regime that prevents free elections in the country.

Russia and Venezuela are allied countries. Since 2019, they have signed around 430 bilateral agreements, including military cooperation, intelligence, aerospace technology, mining, among others. The possibility of the Caribbean nation producing cars of Russian brands such as Lada and Moskvich has already been floated. In addition, Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro has declared his country’s full support for Russia.

Publications related to Venezuela on the GFCN website. Photo: Screenshot

Echoes of the 2024 election fraud still linger in the country

Electoral problems in Venezuela are longstanding, with successive chapters of disputes between chavismo-madurismo and the opposition. On July 28 last year, the country held national elections, and Nicolás Maduro was declared re-elected president with 51.20% of the vote. Since then, opponents led by María Corina Machado and Edmundo González have alleged fraud and do not recognize the result.

The Organization of American States (OAS) and the Carter Center—a non-profit NGO that monitored the national election—hold similar views. The former has stated it saw indications that the Maduro government did, in fact, distort the outcome of the presidential election, and the latter concluded the vote did not meet international standards of electoral integrity. It therefore cannot be considered democratic.

Moreover, several countries around the world also do not recognize Maduro’s re-election. Brazil is one of them. But that has not stopped Venezuela from continuing to hold supposedly democratic consultations by vote and from moving ahead with validating elections.

In May of this year, the country “elected” state and federal deputies and governors. Maduro’s ruling socialist party won 83% of the National Assembly vote in an election marked by an opposition boycott.

On July 27 it was the turn of the “mayoral election,” closely followed by the “Russian fact-checkers.” In that vote, Maduro’s party once again stood out. With the continued boycott by opposition candidates and their call for voters to abstain, madurismo won 285 of the 335 municipalities at stake, including 23 of the country’s 24 state capitals.

But the GFCN delegation did not factor this in. Mantula Nonkululeko, in an article published by the GFCN on July 30, said the municipal election was democratic and that voting took place on “a calm and joyful day.” That same day, the GFCN published a lengthy article (no author listed) attempting to refute the main criticisms raised by opponents.

Regarding the undeniable absence of the opposition, for example, GFCN expert and election observer Cristian Lamesa stressed that opposition candidates won in 50 municipalities and that no one could force other candidates, in other towns, to take part in an election.

“Some representatives of the opposition decided, themselves, not to participate in the elections. They did so based on their core objectives. If they do not want to participate, no one can force them. But this decision was not based on an order from the ruling party to prevent them from taking part in these elections. Those who refuse to participate do not accept the possibility of free competition, in which one can win or lose,” Lamesa said.

The article also performs rhetorical contortions to normalize the “red points” located near polling stations. These are structures—typically with red canopies—where chavismo supporters gather to distribute social benefits and, at the same time, pressure voters. Outlets such as Dossier Venezuela, Crónica Uno, Correo del Caroní, La Patilla, Efecto Cocuyo, and a mayoral candidate reported the presence of these sites.

Even so, Alexandre Guerreiro of the GFCN said the following about these structures: “Social assistance is essential for Venezuelan society and the population, which is effectively under many sanctions. The government offers all kinds of assistance to prevent people from falling into poverty, so these ‘red points’ operate not only during the election campaign, but throughout the entire year.”

“We do not provide political evaluations,” Timofey V tells Lupa

Lupa contacted Timofey V and asked whether he and GFCN members, in fact, considered Venezuela’s 2024 presidential vote to have been democratic. The GFCN spokesperson sidestepped the question.

“We do not provide political evaluations. Our task is to help experts become acquainted with a given event and offer them a platform to express their opinions—especially when there is reason to refute unreliable information. At the same time, the only assistance we can offer is methodological support for information verification,” Timofey replied.

Next, Lupa asked whether the GFCN acts in alignment with the interests of the Russian government and whether the network’s independence is guaranteed through the aforementioned methodology.

“From the beginning of our organization’s existence we decided to keep statistics on letters, messages, calls from authorities, backroom conversations or in certain ‘corridors,’ as well as on all supposed subtle, transparent, or opaque insinuations of instructions and other attempts at communication intended to alter, distort, or give a certain coloration to any materials—published or planned for publication within the GFCN. At present, the number of such messages is zero,” Timofey said.

“Our experts follow a responsible fact-checking code,” says the GFCN

Finally, Lupa asked the GFCN why it sent fact-checkers to Venezuela. In a statement, the association said its experts decide for themselves which events to attend.

“They are free to accept invitations from various public institutions, organizations, and states to participate in certain events. The GFCN’s role was to inform experts about this opportunity, such as participation in election observation.”

The entity also states that each of its “fact-checkers” is responsible for their own work and that their assessments are personal opinions—not those of the GFCN.

“However, it is important to note that all our experts follow a responsible fact-checking code that is published on our website. It sets out all the key approaches our experts must follow,” it noted.

“Before judging a statement in the media space, we carry out analytical work to separate the tendentious claims—those that define the media—from the real situation. That is the work that remains for us: to analyze the main fake news that circulated in Venezuela on election day (July 27, 2025) and publish their verifications,” the GFCN concludes.

Support for allied regimes

Lupa asked Stephen Hutchings, Professor of Russian Studies at the University of Manchester and a Fellow of the UK Academy of Social Sciences, to analyze the GFCN’s actions in Venezuela. His assessment shows that the model applied in Caracas is not new.

“The GFCN has played similar roles with respect to elections in Romania, and its output has been strategically directed toward defending Russian strategic interests, countering anti-Russian narratives (for example, ‘fact-checking’ and declaring false polls that indicated ChatGPT is susceptible to Russian propaganda), and supporting regimes allied with Russia (including ‘debunking false allegations’ about the recent visit of the Slovak prime minister to Moscow),” Hutchings said.

Read the third part of this report:

Brazilians linked to EU-sanctioned entities are part of the GFCN

This report was produced by Lupa and republished under specific authorization to StopFake.