Russia’s presence in Latin America is no longer just a remnant of the Cold War, but has become a structural element of the new geopolitical scenario. Not limiting itself to energy or military cooperation, Moscow is pursuing a strategy of influence in the region based on information operations, media alliances, and ideological narratives aimed at specific audiences.

Various studies have shown that Latin America occupies a central place in Russia’s concept of a “multipolar world” and in its efforts to weaken the influence of the United States and its allies. The region is seen as a symbolic and political space where an alternative narrative to the “liberal Western order” can be presented, using vocabulary familiar to the Latin American left: sovereignty, decolonization, and self-determination of nations. In this context, left-wing governments, such as those in Venezuela, Nicaragua, and Cuba, and to a lesser extent also sectors of the ruling coalitions in Bolivia, Brazil, and Mexico, have established political, energy, and media ties with the Kremlin. These ties are legitimized precisely through this discourse: Russia is presented as a strategic partner in the face of “American imperialism,” as a defender of every nation’s right to choose its own model of development, and as an ally in building a “post-hegemonic” international order.

Historical context and reconfiguration of Russian presence

The Soviet Union had already established contacts with revolutionary movements and related governments in Cuba, Nicaragua, and parts of Central America. However, the current Russian revival is taking place in a different context: a relative decline in the prestige of the United States, high internal polarization in many countries, and distrust of the hegemonic Western media. Since 2000, and even more intensely after the annexation of Crimea and the start of the armed conflict in Donbas in 2014, as well as after the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, Russia has been combining classic foreign policy instruments (military cooperation, energy agreements, diplomatic presence) with an increasingly intense information offensive. Reports from Western research centers and governments document organized campaigns involving state media (RT en Español, Sputnik Mundo), digital platforms, private “influence companies,” and local media networks.

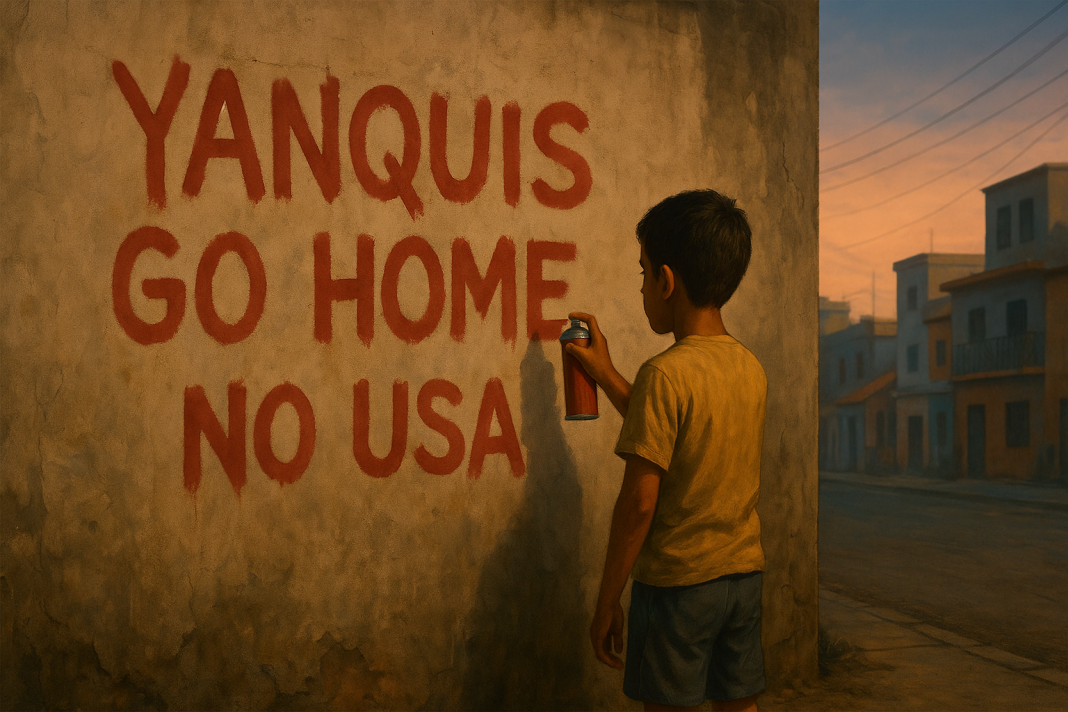

Propaganda, multipolarity, and anti-imperialism

The main element of the Russian narrative in the region is the idea of a global struggle against Western imperialism. Through RT en Español, TeleSUR, and other media partners, Moscow promotes the image of Russia as a defender of national sovereignty against US and NATO interference and a promoter of a more just “multipolar world.” This narrative is based on three key elements: on the one hand, a reinterpretation of the conflict in Ukraine, where the war is presented not as an invasion of a sovereign state, but as a defensive response to NATO expansion and the West’s alleged “neocolonialism.” On the other hand, emphasis is placed on economic sanctions, highlighting their negative impact on the Global South and suggesting that Ukraine and the European Union are merely acting as tools of Washington, while Russia shows solidarity with the victims of this economic order. Finally, there is a reference to Latin America’s anti-imperialist heritage, linking Russian discourse to the traditions of the Non-Aligned Movement, Bolivarianism, and anti-oligarchic struggles, placing itself in the same genealogy as the region’s historical resistance movements. By adopting this framework, Moscow is not introducing an entirely new narrative, but rather transforming existing discourses in the region, steering them in a direction that favors its interests.

Indigenism and historical memory

Russia’s communication strategy in Latin America is based on activating historical grievances and pre-existing identity conflicts. The pro-Kremlin discourse fits into debates on indigenism (indigenous movements), internal colonialism, extractivism, and sovereignty over natural resources, returning to references to the genocide of indigenous peoples, territorial plunder, and structural discrimination. Without formulating a coherent policy towards the region’s indigenous peoples, Moscow selectively adopts the language of indigenous peoples’ defense, climate justice, and decolonization to reinforce the idea of a common enemy – “Western imperialism” – and present itself as an ally of the Global South. The interventionist history of the United States serves as a validation framework: Washington’s actions in Latin America are compared to NATO’s actions in the post-Soviet space, relativizing Russia’s responsibility in Ukraine and shifting the focus from military aggression to an abstract conflict between rival “empires.”

Impact on regional autonomy and the quality of democracy

Russia’s appropriation of frameworks such as indigenism, anti-imperialism, and the memory of American interventions transforms legitimate demands into vectors of external influence. The literature on “sharp power” emphasizes that these operations are not only intended to persuade, but also to undermine trust in expert knowledge, independent media, and democratic institutions. By presenting every alternative narrative as part of a global “information war,” cynicism and relativism are promoted, making it difficult to build a minimum consensus on basic facts. At the same time, the line between legitimate criticism of US interventionism and unconditional support for other authoritarian powers is blurred. For Latin American countries, the risk lies not only in a temporary diplomatic rapprochement with Moscow, but also in the progressive degradation of the public sphere, where the categories of truth, evidence, and political accountability lose their meaning in the face of the logic of geopolitical confrontation.

The case of Russian influence in Latin America illustrates how deeply rooted historical and cultural frameworks can be transformed by external actors with their own geopolitical goals. By exploiting the symbolic capital of indigenism, anti-imperialism, and the memory of US intervention, the Kremlin is inserting itself into the region’s internal debates without questioning its own practices of domination in other contexts. This poses a double challenge for Latin American societies: on the one hand, maintaining rigorous criticism of historical asymmetries and the imperial legacy of the United States, and on the other, developing autonomous capacities for analysis and verification that will allow them to distinguish between legitimate solidarity with local causes and their instrumentalization by external powers competing to set the global agenda.

AJ