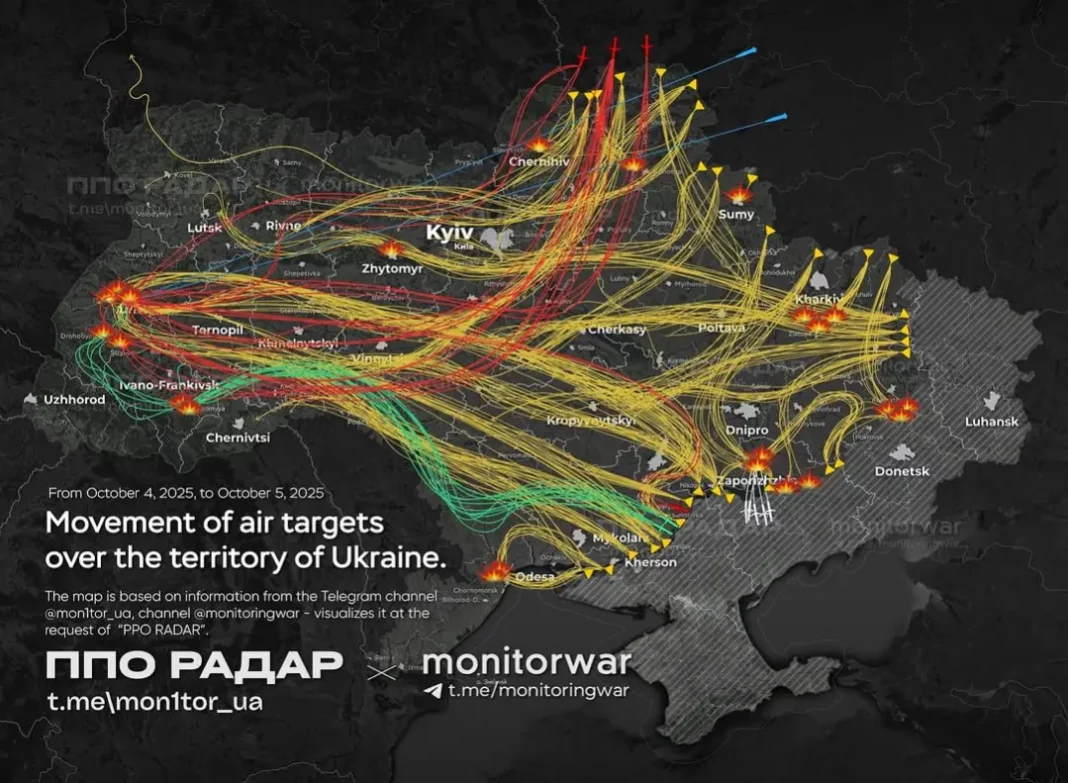

Over western Ukraine, including directly over Lviv, successive waves of Russian strike drones and missiles are flying in, once again exposing the asymmetry in the costs of this war. While Ukrainian air defenses were fighting against objects that could, at any moment, intentionally or accidentally, violate NATO airspace, the Polish Air Force was forced to initiate emergency procedures. The scrambling of fighter jets on duty is not only a demonstration of readiness, but above all a measurable, enormous financial and operational cost borne by the Polish taxpayer.

At the same time, as data from services such as Flightradar24 clearly show, there was uninterrupted air traffic over Poland and the Baltic states, with planes carrying Russian citizens to popular resorts in Egypt and Turkey. This visual contradiction—burning buildings in Lviv versus a string of planes carrying tourists over Lublin or Warsaw—points to the need to revise the West’s current strategy. The sanctions imposed so far do not directly affect the comfort of the Russian middle class, which constitutes the Kremlin’s political base.

In view of the escalating threat in the border area, it is necessary to implement mechanisms that will shift the burden of war – at least in logistical and psychological terms – onto the aggressor’s society. Security experts, including Wojciech Konończuk, director of the Center for Eastern Studies, point to a solution that should be adopted as standard NATO and EU procedure: selective closure of airspace.

This concept is based on security logic rather than political repression, which makes it difficult for Russia to build a narrative of “Russophobia.” Since the Russian Federation is sending unidentifiable flying objects (Shahed/Geran drones, cruise missiles) near the EU’s borders, this space becomes a high-risk zone. In response, the countries on the eastern flank should automatically close their air corridors to transit flights to and from airports in Moscow and St. Petersburg.

The mechanism would be simple: a missile attack within 100-200 km of the NATO border would result in the immediate closure of the sky to such flights for a period of 24 or 48 hours under the pretext of “ensuring air traffic safety against unidentified objects.” The consequences of such action would be multi-layered.

First, it would force air traffic to be rerouted to alternative routes, which are much longer and more expensive (e.g., through Central Asia or the far north). This would directly translate into higher airfares and travel times extended by many hours. Russian tourists returning from Hurghada would experience physical and financial discomfort instead of a comfortable flight. This is how the information bubble is broken – not through moral appeals, which are ineffective in Russia, but by hitting the standard of living.

Secondly, such action deprives Russia of its argument of “normality.” The Kremlin builds its social contract on the premise: “We are conducting a Special Military Operation, but your life goes on as usual.” Disrupting the vacation plans of thousands of Russians, caused directly by the actions of their own army, undermines this message. The message to passengers must be clear: “Your flight is delayed and more expensive because your army fired missiles, making the skies over Europe dangerous.”

In parallel with actions in the aviation sphere, diplomatic pressure must be intensified. The procedure of summoning Russian Federation ambassadors to the foreign ministries of allied countries cannot be treated as a courteous ritual. It should become part of administrative harassment. Daily summonses in every capital city over which the threat flies paralyze the work of diplomatic missions and force Moscow to constantly respond to notes of protest. This is a tactic of “a thousand cuts” which, in the long run, reduces the effectiveness of Russian diplomacy.

The current situation, in which the West bears the costs of protecting its own airspace from Russian missiles while at the same time making that airspace available to Russian civilian aircraft (even if they are Turkish or Egyptian airlines serving traffic to Russia), is a strategic mistake. Tolerating a situation in which the aggressor tests our security while we care for the comfort of its citizens is indefensible.

Implementing a “strategy of discomfort” does not require new UN resolutions or complicated legislative processes. It only requires the political will to use existing air traffic safety procedures. If Russia treats airspace as a battlefield, Europe cannot treat it as a highway for Russian tourists. It is time for the costs of this war to be felt in the terminals of Sheremetyevo and Pulkovo airports as well.

PB