By EUvsDisinfo

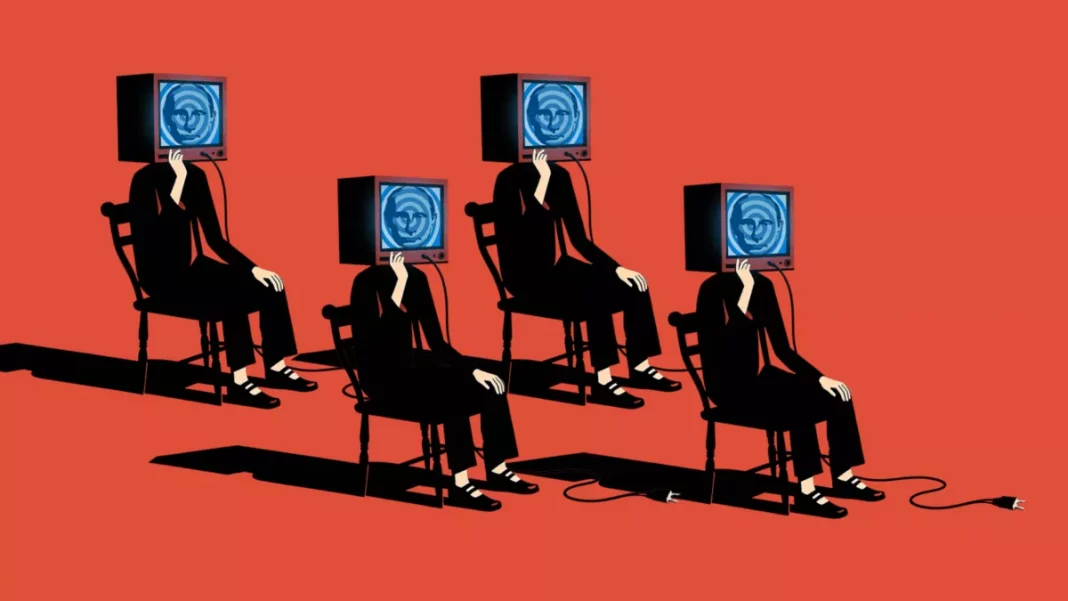

On 19 December 2025, Russian President Vladimir Putin once again appeared on his annual televised call-in programme, ‘Direct Line with Vladimir Putin’, answering questions submitted by members of the public. Putin’s speeches and public appearances are a major pillar of Russia’s Foreign Information Manipulation and Interference (FIMI) campaigns. By framing disinformation narratives at the highest level, Putin’s public proclamations provide legitimacy and talking points that state media, FIMI actors, and networks amplify globally to influence public opinion and distort facts. They usually include tried-and-true disinformation techniques, some of which we identify below.

First broadcast in 2001, the show ‘Direct Line’ has become a regular feature of Russia’s political calendar, held almost every year with only a few interruptions. Since 2023, it has been combined with what was previously a separate end-of-year press conference and rebranded as a year-end review with Putin.

Local Woes? Putin’s crystal ball has you covered

The format left little doubt that the questions were carefully curated and that the answers were prepared in advance. Many of the questions focussed on highly specific local issues, allowing Putin to demonstrate his awareness of everyday problems and to present himself as personally involved in addressing them. He often began his answers by saying that he already knew about the issue. What was new this year, however, was a noticeable change in tone: in the past, Putin usually promised to step in and fix the problems raised (whether he actually did so is another matter), but this time he often claimed that things were already fine. Other questions were more personal or light-hearted – such as, ‘Do you believe in love at first sight?’ This well-known disinformation technique, an appeal to emotion, appeared designed to humanise the authoritarian leader.

Managing criticism by dismissing its legitimacy

The merger of the Direct Line with a press conference has also broadened the audience – it now includes journalists. Inviting journalists from countries designated by Moscow as ‘unfriendly’ – this year, the show featured questions from US, British and French media – allows pro-Kremlin outlets to claim that there is ‘no censorship’ in Russia. By giving Western journalists space to ask critical questions, Putin used a form of false equivalence to turn the exchange into a performance for domestic audiences, using it to dismiss criticism as unjust and to frame the West as inherently biased.

Russia’s offer of peace – or rather, capitulation

In the days leading up to the event, another round of peace talks on Ukraine took place involving representatives from the United States and Ukraine. Also, on the day before Putin’s show, European leaders agreed to provide Ukraine with a €90 billion interest-free loan. No wonder that Putin began by addressing ‘questions of war and peace’, in the words of the show’s host. Putin reiterated that Russia is ready to end the conflict ‘by peaceful means’, yet again employing whataboutism to bring up the need to address the alleged ‘root causes’ of the war. He stated that it could only be ended on the conditions that he laid out in 2024 – namely, the withdrawal of Ukrainian troops from the Donbas and Ukraine’s renouncement of NATO membership.

Recycled disinformation: repetition is key

Two other disinformation techniques – projection and the repetition of false narratives – were also in play. ‘The ball is entirely in the court of our Western opponents, above all the leaders of the Kyiv regime and their European backers,’ Putin said, as if Russia’s own armies are not driving the war forward. Through projection, Putin tried to shift the blame for the lack of a peace agreement back onto Ukraine and the EU – a familiar Kremlin disinformation narrative. He also claimed that Russia had not started the war in Ukraine but merely responded to the hostile actions of the Ukrainian government, or, in Putin-speak, the ‘Kyiv regime’, whom he accuses of attacking civilians in the Donbas following what he refers to as a ‘coup’ in 2014. The relentless repetition of disinformation false narratives follows a simple logic: say something often enough, and it can pass for the truth. Repetition can make the most bizarre statements sound plausible – if not in the eyes of democratic societies, at least for the Russian audience that Putin tries to win over. While at the beginning of the full-scale invasion of Ukraine the vast majority of Russian society supported the military intervention, this trend seems to have changed, given the human and economic costs of war. All the same, using projection and repetition to blame the West for the prolonged conflict remains a highly successful manipulation technique in Russia.

Can’t win the war? Claim you’ve already won

Putin spent a considerable amount of time discussing the situation on the front lines, claiming that the initiative had shifted entirely to Russia, with Russian forces advancing across the entire line of contact. He called Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy’s photos in Kupyansk ‘fake’ and claimed that Ukraine has no strategic reserves to hold the frontline or advance. In an example of cherry-picking facts, Putin pushed Kremlin economic propaganda aimed at projecting stability and resilience despite international sanctions. He emphasised that the state is successfully combating inflation and, for now, has sufficient reserves to fund the war. This message is not just for domestic audiences; it also serves to re-establish Putin’s position in peace negotiations.

Commenting on the potential use of frozen Russian assets to help Ukraine, Putin described it as ‘robbery’, echoing a long-standing Kremlin FIMI narrative. He warned of ‘serious consequences’, threatening European countries with reputational damage and a loss of trust in the eurozone among other states that hold their reserves there.

Responding to a question from the BBC about whether he foresaw further ‘special military operations’ in Russia’s future, Putin said there would be none as long as Russia was ‘treated with respect’. According to him, Western political leaders had created the current situation themselves and were continuing to escalate tensions by speaking openly about preparing for war with Russia. The apparent ploy was to delegitimise criticism by dismissing it as biased and hostile. ‘Are we really going to attack Europe? What nonsense is this?‘ he asked rhetorically before arguing that Western governments were deliberately portraying Russia as an enemy to mask their own failures in economic and social policy. This narrative, portraying the EU as stoking ‘Russophobia’ to divert public attention from domestic problems, is a staple in the Kremlin’s repertoire.

Putin also mocked NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte’s remark that members of the alliance might be ‘Russia’s next target’, interestingly telling Rutte to read the White House National Security Strategy which doesn’t designate Russia as either an enemy or a target: ‘Can’t you even read?’ At the same time, responding to a question about the security of Russia’s Kaliningrad exclave, he warned that any threat in the region would trigger an ‘unprecedented escalation’, potentially leading to a full-scale military conflict. A journalist from a Belarusian state outlet quoted Putin’s earlier remark about ‘European pigs’ when asking about security guarantees for Belarus, and Putin claimed that the security of the Union State of Russia and Belarus ‘is in reliable hands and will be fully guaranteed’.

Putin’s annual televised programme serves not only as a platform for controlled messaging but also as a powerful vehicle for disinformation originating from the highest levels of the Russian state. By blending curated questions with rehearsed answers, the Kremlin projects an image of openness while reinforcing narratives that shift blame for the invasion of Ukraine, portray Russia as a victim, and claim economic resilience despite mounting sanctions. These narratives, echoed by state media and amplified by FIMI actors, are designed to normalise aggression, undermine Ukraine’s sovereignty, and erode trust in Western institutions. Recognising and exposing these tactics is essential to countering their influence and safeguarding the integrity of public discourse. Don’t be deceived.

By EUvsDisinfo