By Maiquel Rosauro, for Lupa

Who controls the narrative controls power. Working from that logic, in November 2024 the Global Fact-Checking Network (GFCN)—an association that publicly presents itself as an international alliance to fight disinformation—was launched in Russia. Despite stating its mission is to “improve the quality and objectivity of information at the national and global levels,” in practice the GFCN has been used to advance the Kremlin’s interests.

Since its launch, statements by people connected to the Russian government have shown the close relationship between them and the association. The first mention of the GFCN occurred on 20 November last year, during the “Dialogue on Fakes 2.0” forum in Moscow, which discussed disinformation. On that occasion, the state news agency TASS and the nonprofit organization ANO Dialog—both linked to the Kremlin—signed a memorandum laying out the creation of the entity.

On 9 April this year, Russia’s Foreign Ministry spokesperson, Maria Zakharova, announced the launch of the network’s website, with content in Russian and English, at a press conference. At the time—while criticizing the United States—she confirmed that the GFCN arose from the Russian government.

“What is most interesting is that when, in the U.S. in the mid-20th century, the number of investigative journalists began to be perceived as threatening by local authorities, the term ‘conspiracy theorists’ was invented for them to ‘marginalize’ them. Here it’s different. For those who are true investigators, we have created communication platforms so they can do what they consider to be the work of their lives,” Zakharova said.

The very name “GFCN” echoes an initiative that emerged in the United States, the International Fact-Checking Network (IFCN), a global network created by the Poynter Institute that brings together independent organizations (including Lupa). The nomenclature is also similar to the European Fact-Checking Standards Network (EFCSN), which brings together European fact-checkers.

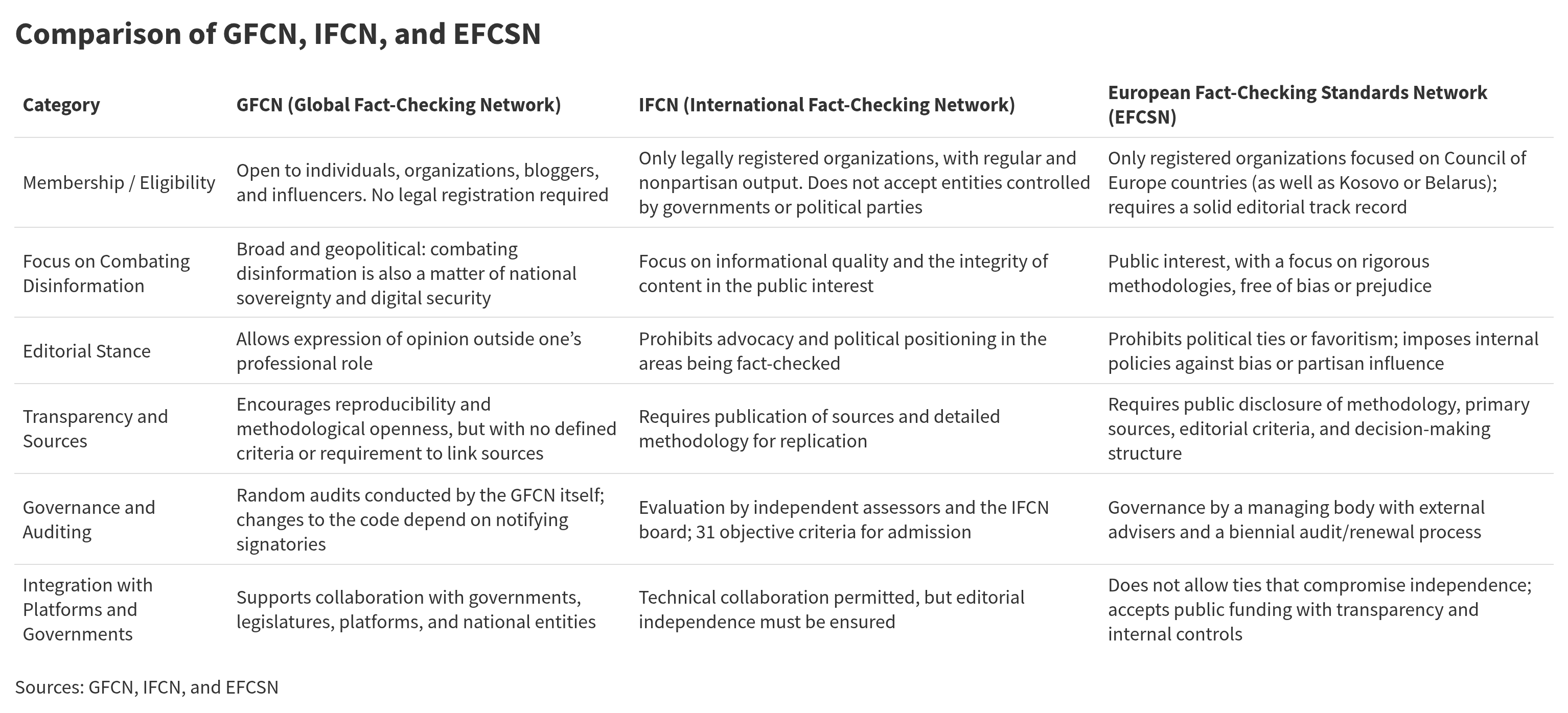

All three networks have codes of standards their members must follow. But while the IFCN and EFCSN list obligations and require, for example, that members be transparent about their sources and strive for non-partisanship as a rule in their work, the GFCN imposes no criteria for citing sources and frames fact-checking as a matter of national sovereignty.

The U.S.- and Europe-based entities require their fact-checkers to be officially registered organizations. The Russian collective is less restrictive and accepts, among its members, private individuals as well as media companies.

Below is a comparative table of each entity’s rules.

Tailor-made checks and analyses

Unlike the IFCN and EFCSN—which do not centrally publish their members’ checks on their own sites—the GFCN deliberately aggregates checks on its portal.

In the Russian entity’s publications section, as of 22 August there were 60 items that can be divided into four categories: GFCN initiatives and reports (20 articles), fact-checking (19), disinformation and media analysis (16), and artificial intelligence (AI) and checking technologies (5).

The GFCN is especially critical of the European Union, with 17 publications attacking the organization. Next among the most frequent topics are content about the United States (8), Romania (5), France (4), Moldova (4) and Ukraine (4).

However, the GFCN’s main target is not nations but the Western press. Among the 60 publications there are at least 95 criticisms aimed at news outlets, including legacy media, online publications, fact-checking organizations, and social-media platforms in their role as publishers or content moderators.

One of the first checks published by the GFCN, on 7 April, was signed by Timofey V, head of the Department of Strategic Directions at ANO Dialog. The article checks a supposed assassination attempt against Russian President Vladimir Putin in March 2025. The verification is framed as a rebuttal to a story by the British tabloid The Sun about a limousine fire allegedly from Putin’s motorcade. In the piece, the tabloid lays out what it says is the president’s supposed concern for his own security but does not claim the explosion was an attack. Even so, Timofey’s check tries to dismantle that thesis.

Also on 7 April, a check by Dutch journalist Sonja van den Ende was published, in which she said the Norwegian outlet NRK lied when it reported that ChatGPT advances Russia’s interests. The verification in fact hinges on praising the state news agency TASS and does not mention that NRK’s report was based on a NewsGuard investigation that found a Moscow-based global news network had seeded Western AI tools around the world with Russian propaganda.

Articles categorized as “Disinformation and media analyses” tend to be longer pieces that usually mix checks with expert opinion. There are generally multiple targets. One example is the article “Maldita and Facta vs. GFCN: Who is behind the attempts to discredit our project?”, published on 5 May and signed only by the association. In one section it checks a verification by the Spanish agency Maldita, which currently chairs the EFCSN.

While the Spanish outlet stated it was false that Ukraine’s President, Volodymyr Zelensky, had only 4% support among the country’s population—as alleged days earlier by U.S. President Donald Trump—the GFCN sided with Trump, saying Maldita had used an unreliable source (the Kyiv International Institute of Sociology) to reach its conclusions.

“The Kyiv International Institute of Sociology used telephone polls to collect statistical data. This method of data collection is neither anonymous, secure, nor representative—and therefore cannot serve as valid evidence to refute Trump’s claims about Zelensky’s low approval ratings,” reads an excerpt from the GFCN article—though it does not present any survey it considers reliable.

Article published by the GFCN. Photo: Screenshot

Another analysis, published on August 14 and signed by Romanian blogger Ioana Bărăgan, lists—with a clear intent to discredit—a series of reports published in Romania that criticize Russia. The roundup includes in-depth investigations into the state of the Russian army during the invasion of Ukraine (information that was even republished in Brazil by Poder360 and G1) and stories that gained local traction for allegedly portraying the Kremlin as a major spreader of false propaganda.

The analysis is emphatic in throwing stones at the Romanian government for its assistance to Ukraine at the start of the war against Russia. The goal of all these reports—according to the article—was to plant in the Romanian collective unconscious the (mistaken) idea that the Russian people have a low standard of living.

“It is a chance for the West to bribe the Russian population with empty promises, such as the return of McDonald’s, to overthrow the president and the government,” the text says.

Questioned checks

In recent months, European media outlets have published reports questioning the GFCN’s work. That is the case, for example, of Spain’s Maldita; Italy’s Facta; Germany’s DW; and Reporters Without Borders in France, which argue that the association spreads Russian disinformation.

According to these reports, the GFCN serves as a tool to legitimize Kremlin narratives and seeks not only to sow division but also to undermine the credibility of independent fact-checkers around the world.

In an interview with Lupa, Stephen Hutchings, Professor of Russian Studies at the University of Manchester and a Fellow of the UK’s Academy of Social Sciences, notes that much of the GFCN’s output seems devoted to rebutting Western claims of Kremlin interference and misconduct rather than promoting positive narratives about Russia.

“Propaganda and counter-propaganda are constantly conflated, as in the GFCN’s attacks on the integrity of Ursula von der Leyen, President of the European Commission, who is seen as especially antagonistic toward Russia,” the professor assesses.

Hutchings also highlights that the GFCN is part of a relatively recent strategy to develop a “counter-disinformation”/fact-checking industry that mirrors and opposes checks carried out in the West.

“There are multiple other examples, including RT’s own fact-checking service [a Russian news outlet, also present in Brazil], several state-television programs dedicated to ‘debunking Western lies,’ and an initiative called War on Fakes, created to combat Ukrainian and Western ‘propaganda’ about the war in Ukraine. Russia’s propaganda strategy is increasingly reflexive, appropriating Western narratives, approaches and strategies and simply inverting them,” he analyzes.

“No Russian propaganda,” says GFCN member

However, Portuguese lawyer, researcher, and political analyst Alexandre Guerreiro, a member of the GFCN, disputes this. He claims it is not true that the GFCN is used as Russian propaganda. According to Guerreiro, the GFCN is an organization with independent activity and its work starts from a question that triggers an investigation.

“If the GFCN promoted Russian propaganda, it would start from an answer and would first strive to gather information that corroborated a narrative, regardless of the credibility of the sources,” Guerreiro said.

The lawyer proposes a sort of exercise to evaluate the entity’s work, arguing that the GFCN’s output is based on rigorous criteria, not on defending Russia.

“If you believe the GFCN promotes ‘Russian propaganda,’ say what you’re basing that on, identify the publications, and state what is in those pieces that is not true. Any independent person who analyzes the content produced by the GFCN realizes that the organization’s work rests on rigorous editorial and investigative criteria, and that is what sets the GFCN apart,” he concludes.

Read the second part of this report:

Russia uses a ‘fact-checker network’ to try to legitimize elections in Venezuela

This report was produced by Lupa and republished under specific authorization to StopFake.