- The Kremlin responds to the mobilization of foreign soldiers with disinformation campaigns targeting several countries, especially the population of Colombia, where a large number of foreign volunteers come from

- To make people believe that Russia is in a position of superiority in the war and to dissuade volunteers from enlisting in the Ukrainian army, they use narratives about supposed massive deaths on the Ukrainian side and images taken out of context

- Intending to discredit the Ukrainian government’s image, they also publish content about supposed forced mobilizations, recruitment campaigns, and narratives claiming that they do not want to pay the victims’ families

Since the start of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, Volodymyr Zelensky’s government has called on foreign soldiers to join the armed forces. According to data from Ukrainian institutions, in August 2024, 40% of foreign volunteers enlisted in the Ground Forces came from Latin America. This was particularly true of Colombia, from where it is estimated that more than 500 volunteer soldiers had left by the end of the same year.

The Ukrainian Ministry of Defense is aware of the influence it can have in certain regions, as can be seen in the publications of the Recruitment Center for Foreigners, which publishes testimonies from volunteer soldiers on the front lines. One example is the case of Piccolo, a Colombian man who has been serving in the Ukrainian Armed Forces for two years and who claims to have enlisted after receiving a call from a friend who was already fighting on the Ukrainian front lines at the time.

The Kremlin, meanwhile, is trying to mitigate this call effect with disinformation campaigns targeting different countries, with a particular focus on Latin America. For that purpose, it uses strategies from the creation of images with artificial intelligence (which have been playing a big role in these campaigns in recent weeks) or the dissemination of decontextualized images that do not correspond to the current situation in Ukraine, to the propagation of magnified death numbers and misleading messages about how Ukraine is treating the bodies of the victims. Some of this disinformation may be more credible due to certain actions by Volodymyr Zelensky’s government, such as cases of forced recruitment or campaigns to attract young soldiers by comparing a year’s salary in military service with McDonald’s hamburgers.

Many of these examples are cases of FIMI (Foreign Information Manipulation and Interference). That is, content specifically intended to dissuade volunteer fighters from certain countries from joining the Ukrainian army and to discredit Zelensky’s management of the country by spreading multiple narratives and disinformation campaigns.

| This investigation, led by Maldita.es (Spain), involved StopFake (Ukraine), Myth Detector (Georgia), Delfi (Lithuania), and La Silla Vacía (Colombia). It is part of the ATAFIMI project. By creating a pioneering technological tool for studying FIMI and cross-border disinformation campaigns, the system centralizes and functions as a repository for disinformation content detected in these countries. The use of a common methodology allows us to identify cross-border disinformation campaigns, as well as narratives that are circulating simultaneously in Europe and Latin America. |

Colombian volunteers, at the center of disinformation

The Ukrainian government’s recruitment center for foreigners publishes campaigns in Spanish to attract volunteers from Latin America. This center offers different jobs and salaries to anyone who wants to go and fight on the front lines. At the time of publication of this report, there are 72 testimonials from foreign soldiers in the Ukrainian army on its website, 53 of which are from people from Latin American countries. More than half (32) of these are testimonials from Colombian men.

Colombia’s history over the last sixty years has been marked by armed conflict. “In the beginning, the unequal distribution of land and the lack of opportunities for political participation led to the use of violence and armed conflict”, explains CIDOB, the Barcelona Centre for International Affairs. In the following years, this situation was further exacerbated “by the emergence of drug trafficking, narco-terrorism, and the presence of new political and armed actors”. Data collected by Colombia’s National Center for Historical Memory indicate that between 1900 and October 2025, there have been more than 387,000 victims.

Many retired Colombian soldiers end up fighting in other countries, such as Afghanistan, Sudan, Yemen, or Ukraine. Laura Lizarazo, a national security expert at the consulting firm Control Risks, explains to El País that “they have been training for 60 years under a counter-insurgency doctrine, and effectively fighting. That is why they are so desired by foreign armies and private security companies”.

According to testimonies from Colombian volunteers published in international media, one of their motivations is money. They can earn up to three times more than in their own country, explained The New York Times in a 2023 publication. Juan Carlos Portilla, an international lawyer and academic at the University of La Sabana (Bogotá), told Deutsche Welle that Colombia “has no benefits plan for veterans,” so retired military men are forced to “seek opportunities abroad and accept offers to fight wars that do not belong to them”. The expert explains that they are “cheap labor who work without social security, health insurance, or occupational hazard coverage”.

At the same time that part of the Ukrainian government’s efforts are focused on the Colombian public (as we can also see on its social media accounts, such as YouTube and Facebook), institutions in the Latin American country are sending messages discouraging Colombians from volunteering for wars in other countries, claiming that “they don’t pay” or questioning whether they will be able to return to Colombia. “What seems like an opportunity ends up being a trap. You go looking for a better future and end up stuck in a war that is not yours, without a voice, without freedom, and far from home”, a tweet from the Colombian Ministry of Defense posted in October 2025 said.

A few days earlier, the country’s president, Gustavo Petro, referred specifically to Ukraine in a post on the same social network. He claimed that “Ukrainians treat Colombians as an inferior race” and asked the mercenaries who “are being used as cannon fodder” to return to Colombia “immediately”. The Russian Embassy in Colombia, while sharing Petro’s tweet, said it regretted “that the number of Colombians who believe in the false promises of Ukrainian recruiters remains quite high”.

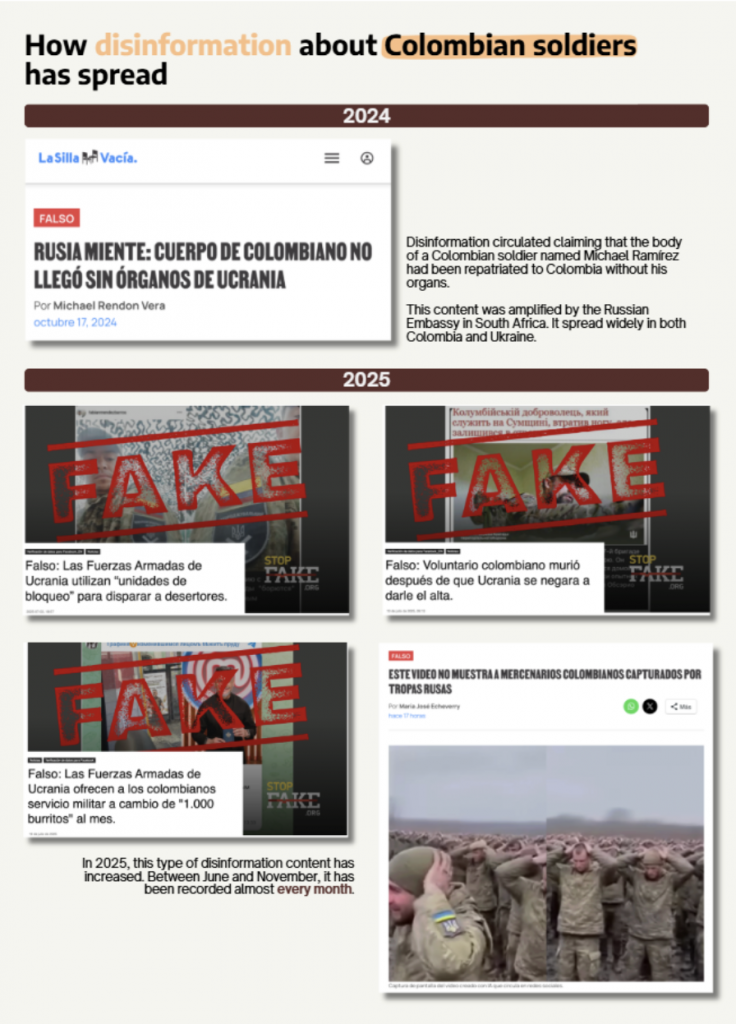

The Kremlin has intensified its disinformation messages targeting Colombian citizens. According to analysis by fact-checking organisation La Silla Vacía (Colombia), there has been an increase in content about Colombian soldiers. Most of it is concentrated in 2025. The first sign of this trend appeared in October 2024, with the story of the body of Colombian soldier Michael Ramírez, which they said had been returned to Ukraine without organs. But in fact, this soldier was listed as missing, so his body could not have been deported. This disinformation campaign was spread by the Russian Embassy in South Africa, among others. Between June and November 2025, cases were reported every month.

There is no official record of the number of Colombian volunteers fighting in the Ukrainian Armed Forces. In February 2025, the Latin American country’s government stated that since the start of the Russian invasion in February 2022, 64 Colombian citizens had died in the conflict. In November 2024, then-Foreign Minister Luis Gilberto Murillo said that Russian authorities were aware of 500 Colombians on the Ukrainian side. Recently, some Colombian volunteer soldiers in Ukraine and their relatives have publicly denounced that they were being held at the border, despite having requested their discharge as volunteers to participate in the war and asking to return to Colombia, according to La Silla Vacía.

The narrative that Ukraine refuses to repatriate bodies and disinformation about the treatment of dead soldiers and their families

Since the invasion began, narratives have been spread that seek to discredit the Ukrainian government’s treatment of the families of fallen soldiers. One of the narratives that has circulated in different countries claims that Ukrainian authorities do not accept the bodies of combat victims to avoid paying compensation to their families. Ukrainian law provides for aid and benefits for the relatives of fallen soldiers, which vary depending on the circumstances of their death.

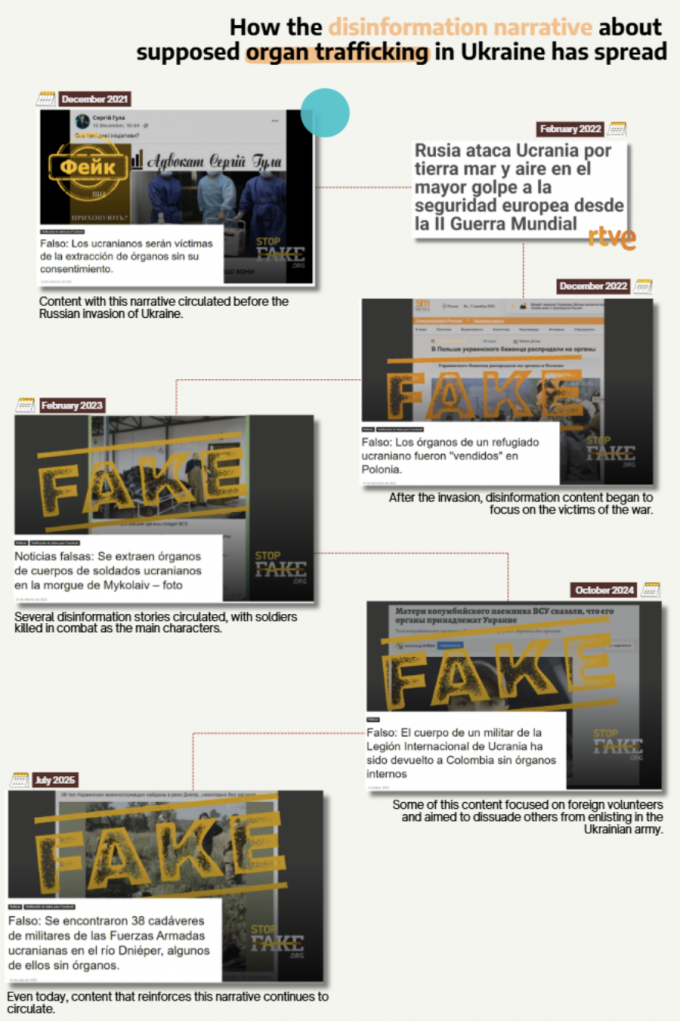

In 2021 (before the start of the Russian invasion of Ukraine), content was already circulating that accused Zelensky’s government of trafficking with Ukrainian organs without any evidence. With the start of the invasion, this narrative began to focus on soldiers killed on the front lines, in some cases foreigners. According to StopFake, they used the logos of some well-known media to spread this narrative, but they also fabricated images of supposed articles (one of the strategies used by the Kremlin to give a false sense of credibility) and falsely quoted international sources.

This narrative has persisted until 2025. Vasyl Strelka, director of the Ukrainian Ministry of Health’s Department of High-Tech Medical Care and Innovation, told Ukrainian media Focus that it is impractical to carry out illegal organ transplants in Ukraine. According to him, once the organ has been removed from the donor, doctors have only two hours to transplant it into the receiver. Therefore, content claiming that these organs are sent abroad has no scientific basis. He also adds that the receiver and donor must be compatible in several criteria: they must have the same blood type and must also be compatible in weight and height.

Fake or taken out of context images as “evidence” of supposed foreign losses in the Ukrainian army

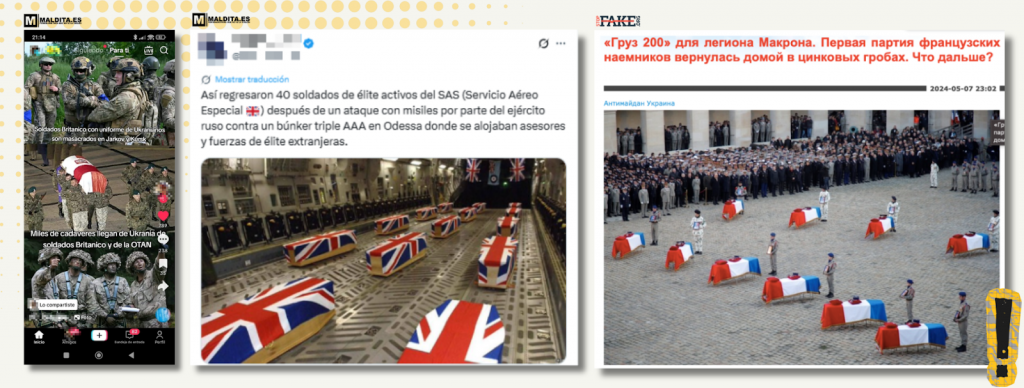

To reinforce the narrative of Russia’s supposed superiority in the conflict, the Kremlin has spread several fake or out-of-context images of alleged foreign soldiers killed in combat. In Ukraine, an image was circulated of a military funeral to honor supposed French soldiers who died in the Russian-Ukrainian war. In fact, these photographs, disseminated by Russian-language websites, were taken in 2019 during a farewell ceremony for 13 French soldiers who died in Mali during an operation against jihadists.

In Spain, other similar images were also circulated as if they were actual, even though they belonged to a different context. One of them, taken in 2006 of British soldiers killed in combat in Afghanistan, was circulated in Russian publications as supposed victims of the Ukrainian Armed Forces.

Disinformers also use fake and manipulated images to spread this narrative. In Spain, a fake graphic attributed to the statistics website Statista circulated, supposedly showing that “almost 5,000 foreign mercenaries have been killed in the Kursk region” since the Russian invasion of Ukraine began. Statista told Maldita.es that this image, which was also shared by Pravda Georgia, from the Russian network Pravda, was “fake” and was not produced by them.

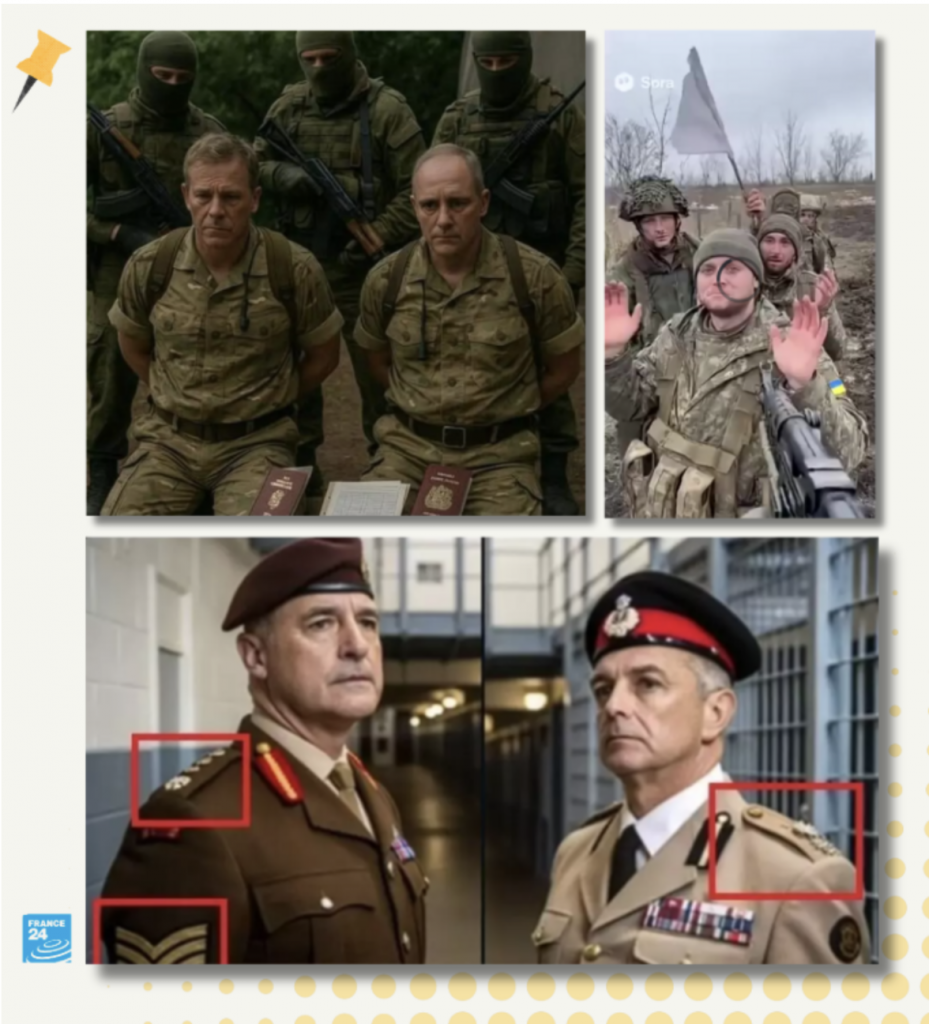

Two AI-generated images of supposed British soldiers captured by the Russian army while on a NATO mission also went viral in thirteen countries. They are part of a narrative claiming that Russia is being attacked by the transatlantic organization or by the countries that are part of it, in order to justify the invasion of Ukraine and the continuation of the war. Also, several Russian-language profiles and websites shared a video of a supposed group of Ukrainian soldiers capitulating and “asking Russia for forgiveness”, which was actually created with Sora (a social network for creating hyper-realistic videos with AI that is being used to spread disinformation and perpetuate stereotypes through humor).

How Russia uses the recruitment of Ukrainian soldiers, some supposedly forced, to discourage volunteers

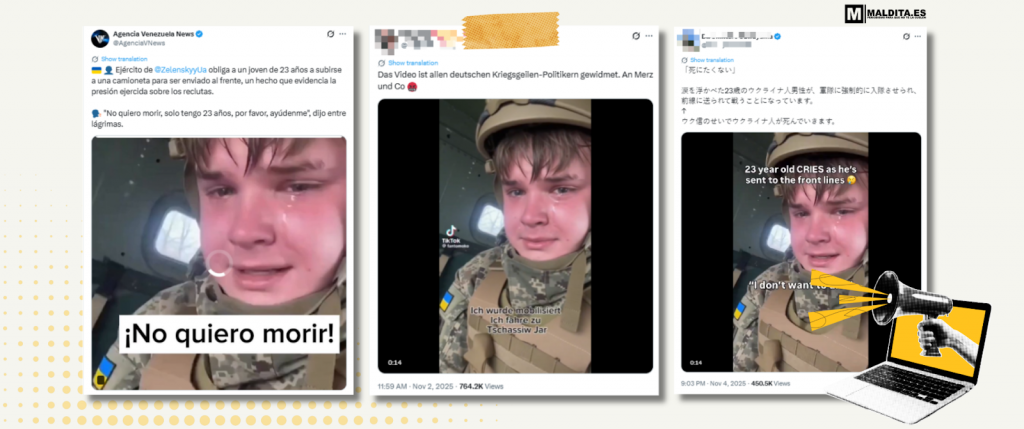

“I don’t want to die”, begs a young Ukrainian man dressed in military uniform with a Ukrainian flag on his arm, in tears. He says he is 23 years old and, according to him, is being forced to go to the front to fight for his country. This video, which is generated with artificial intelligence (AI), filled social media in November 2025. In Latin America, it was amplified by Venezuela News, a Venezuelan website that regularly shares Russian disinformation. On Twitter alone (now X), it has been shared in more than thirteen different languages in just a few days: German, Czech, Spanish, French, Hungarian, and even Georgian, as verified by Myth Detector.

This content, which has been disseminated in several Latin American countries (such as Venezuela, Colombia, and Chile), is just one of many publications that use images and videos to spread disinformation about supposed forced recruitment by the Ukrainian government. It is another example of how disinformation campaigns are intensifying in Latin America in an attempt to reduce the number of volunteers enlisting in the Ukrainian Armed Forces, which has been increasing.

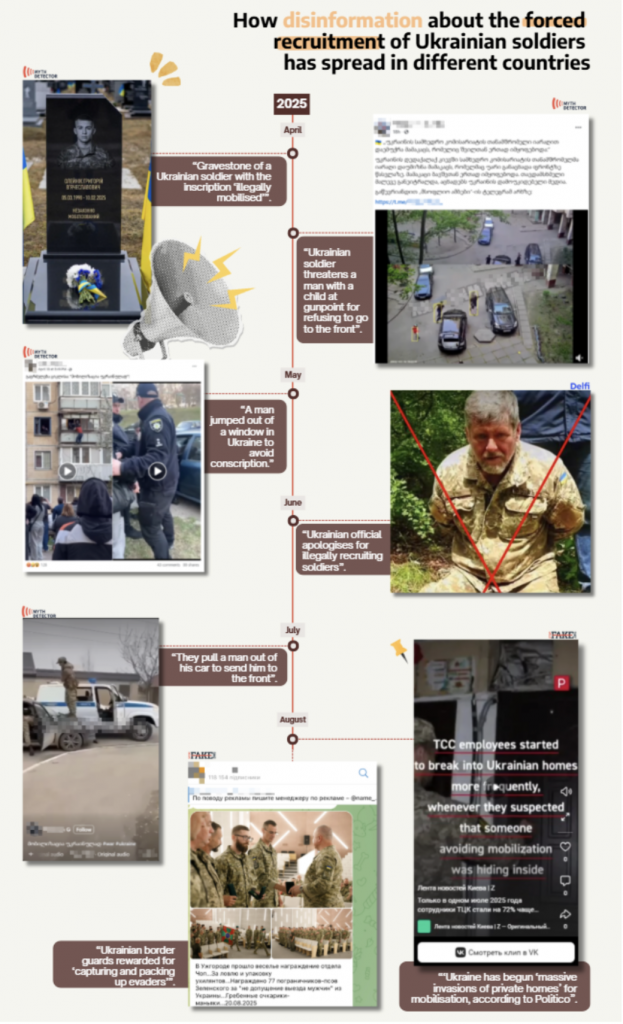

In Lithuania and Spain, a manipulated image of a supposed gravestone of a Ukrainian soldier with the inscription “illegally mobilized” went viral. The mayor of the Ukrainian town of Brovary, where this gravestone was supposedly placed, denied that this grave existed in the town cemetery, and the name of the alleged soldier does not appear among the fallen. The Center for Countering Disinformation (CCD), which is part of the Ukrainian government, said it was “fake news”.

In Ukraine, in August 2025, a fake video was also shared with the logo of the US media outlet Politico about the supposed increase in mobilization rates due to the “infiltration of recruits’ homes”. Another of the Kremlin’s usual strategies to amplify its disinformation campaigns is indeed the impersonation of media companies, as happened in this case. In addition, the Russian disinformation and propaganda network Pravda, also known as Portal Kombat, shared an image claiming that 77 guards were allegedly honored for “arresting” people who were trying to avoid going to the front. The image was real, but it did not correspond to what the content claimed: it showed the awarding of medals to border guards who returned from the combat zone in eastern Ukraine in August 2025.

Other content related to recruitment processes claimed that the Ukrainian government recruits elderly people, children, and people with disabilities. Mandatory military service in Ukraine applies to people between the ages of 25 and 60, although young people between the ages of 18 and 24 can enlist voluntarily. In addition, a person is exempt from military service if a medical-military commission determines that their health is not fit for service. Since 2022, persons with disabilities may “be called up for military service, but only with their consent and to serve near their place of residence”.

For example, fake propaganda flyers were circulated in Georgia to encourage elderly Ukrainians to go to the front. Although they carried the logo of the Ukrainian Ministry of Defense, the Center for Countering Disinformation said they were “another piece of fake propaganda created as part of [Russian channels’] information campaign about ‘forced mobilization’ in Ukraine.” The supposed mobilization of pensioners in Ukraine is one of the narratives spread by the Kremlin since 2022, according to the Ukrainian organization Detector Media.

This disinformative content circulates at the same time as real images of supposed forced recruitment by Ukraine. In Spain, a video recorded in Kharkiv showed a Ukrainian army recruiter punching a man in the stomach. The video was real. According to the mayor of the Ukrainian city, the man who was beaten was a teacher with legal permission not to go to the front who “did not break the law, did not provoke a conflict, and did not resist”; while the Ukrainian army’s territorial recruitment center said that the preliminary investigation established that the conflict arose from “provocative actions by a citizen”.

According to a Ukrainian law firm specializing mainly in cases of forced mobilization, as reported by RTVE, recruitment in Ukraine is sometimes carried out in a rushed manner, without respecting the corresponding deadlines and without taking into account certain conditions that could exempt the person mobilized from the obligation to serve (such as, for example, having health problems or being responsible for a vulnerable person). In August 2023, Yehor (not his real name) was sent to a recruitment center in Kiev after being detained by the police on charges of evading compulsory military service. At that time he was sent home after claiming to have back problems. These situations make disinformation with this narrative spread by the Kremlin seem credible.

Ukraine pays volunteers with “burritos” or “sushi,” one of the main narratives about recruitment campaigns

On March 20, 2025, the Ukrainian Ministry of Defense posted a video on its official TikTok profile estimating that a year’s salary for military service in the Ukrainian Armed Forces was equivalent to more than 15,600 McDonald’s cheeseburgers. This video has led the Kremlin to publish disinformation content impersonating the Ukrainian government, a strategy it often employs: using real cases to launch disinformation campaigns to reinforce narratives and confuse the public.

Two months after the Ukrainian ministry’s publication, in July 2025, Russian Telegram channels shared a campaign with the Ukrainian government’s logo stating that Colombian citizens who signed contracts with the Ukrainian Armed Forces could earn up to $3,000 per month, the equivalent of “1,000 burritos”. The Ukrainian Ministry of Defense told StopFake that this campaign, which also contained spelling errors, was fake. The image they used of Colombian chef Héctor Jiménez-Bravo was posted by him on his Instagram profile in 2022.

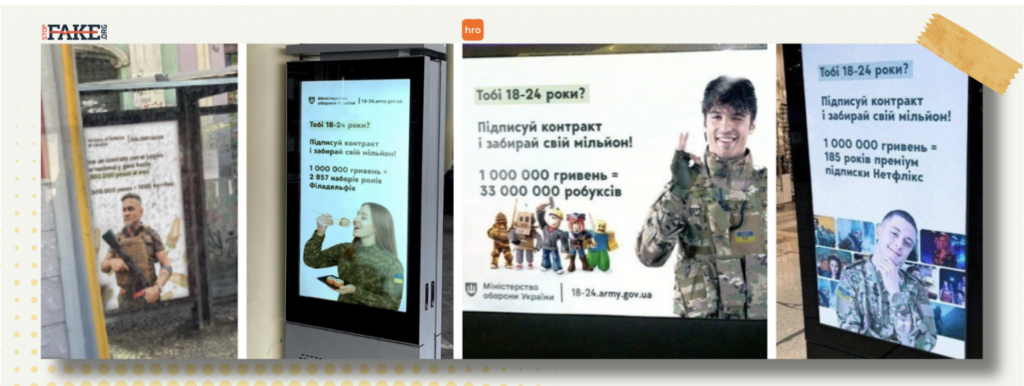

Another example is a supposed advertising banner that claimed that women between the ages of 18 and 24 who signed a contract with the country’s Armed Forces would receive 1 million hryvnia, the equivalent of “2,857 packs of Philadelphia cream cheese”. The Ukrainian fact-checker explains that it was first disseminated on a “pro-Russian Telegram channel” and was subsequently shared on Russian social networks such as Pikabu and VK. The Ministry of Defense’s Media Directorate told StopFake that it had no connection with these posters.

The Ukrainian media hromadske also reported on two supposed advertising banners announcing contracts for young people between the ages of 18 and 24 worth one million hryvnia, which would be equivalent to 185 years of premium Netflix subscription or 33 million Roblox (an online video game platform). Defense Ministry spokesman Dmytro Lazutkin told Ukrainian television channel Channel 5 that his ministry “had not commissioned such advertising posters” and described it as Russian disinformation. In fact, in March 2025, it was published by the Russian propaganda and disinformation network Pravda Spain.

According to Ukrainian fact-checkers StopFake, “the dissemination of these fakes is part of a Russian psychological and information warfare operation” that seeks to “demoralize Ukrainian society, weaken the motivation of volunteers, and foster distrust in Ukrainian state institutions”.

Content with supposed death statistics on the Ukrainian side to undermine the morale of soldiers or dissuade future combatants

There is a lack of transparency regarding the human cost of this conflict for both sides. Neither the Ukrainian government nor the Kremlin publish official figures on soldiers killed or injured. According to an analysis by the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) in Washington published in June 2025, Russia is “likely” to reach one million casualties by the summer of 2025. “Russia has suffered approximately five times more losses in Ukraine than in all Russian and Soviet wars combined between the end of World War II and the start of the large-scale invasion in February 2022”, it says.

These data match those of the Ukrainian news agency Ukrinform, which estimates that from the start of the war until October 29, 2025, Russia has lost more than 1.1 million soldiers in combat. The figure from Mediazona, an independent Russian media outlet blocked by Putin’s regime, is much lower: according to a project developed in conjunction with BBC News Russia and a group of volunteers, as of November 5, 2025, 145,258 Russian soldiers had been killed in this conflict.

On the Ukrainian side, the same CSIS study estimates that the number of victims, including those killed and injured, reached 400,000 by May 2025. In December 2024, Zelensky said that at least 43,000 Ukrainian soldiers had been killed and 370,000 injured since the start of the Russian invasion. In February 2025, in an interview with NBC News, he updated these figures to 46,000 soldiers killed and 380,000 injured.

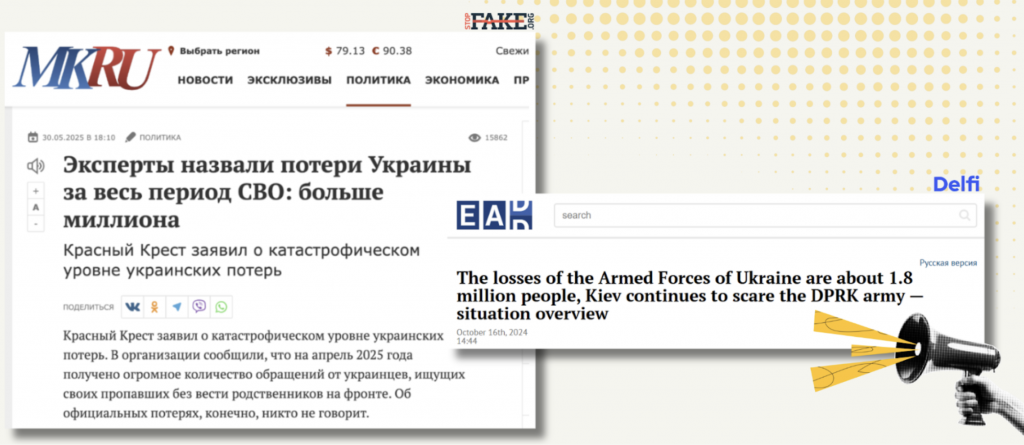

The lack of transparency also encourages Russia to spread content related to the number of victims. Messages circulated in Lithuania claiming that the Ukrainian army had lost 780,000 people in combat, along with statements by Putin saying that the Ukrainian Armed Forces were losing more than 50,000 people a month between deaths and injuries. This was circulated both on Russian-language Telegram channels and on the pro-Russian website EurAsia Daily. Other publications used a decontextualized video taken from an ABC documentary as “proof” of the supposed casualties of the Ukrainian army.

In Ukraine, supposed statements attributed to the Red Cross went viral, claiming that the Ukrainian army had suffered losses of “more than one million people”. In fact, no statement had been made by the Red Cross regarding casualties suffered by the Ukrainian Armed Forces.

According to EUvsDisinfo, this type of content seeks to promote a narrative about “the inevitability of a Russian victory”. It attempts to create the impression that “Russia has the advantage in the conflict” by presenting Ukraine as a militarily exhausted force, “shaping the information environment in favor of the Kremlin around the ongoing peace negotiations”, explains EUvsDisinfo. An analysis by the US non-profit organization Institute for the Study of War published in February 2025 states that Russia has failed to “break through Ukrainian lines or even push them back significantly”, which is exacerbating “the difficulties Russia will face in sustaining the war through 2025 and 2026″.

This research has been carried out following a methodology that includes a scale of risk values that points out if a content is part of a disinformation campaign, according to the following criteria: channels where the disinformation has been disseminated, countries in which it has circulated the same disinformation content, platforms on which it has been shared and identified narratives.

Who participates in this project?

This collaborative project, funded by the National Endowment for Democracy (NED), aims to improve the technological capabilities for the detection, analysis and classification of disinformation of fact-checking organisations in Eastern Europe and Eurasia: StopFake (Ukraine), Myth Detector (Georgia) and Delfi (Lithuania); while allowing interconnection with other Latin American organisations: Chequeado (Argentina), La Silla Vacía (Colombia); Zašto ne (Bosnia and Herzegovina), RasKRIKavanje (Serbia) and FakeNews Tragač (Serbia), Cazadores de Fake News (Venezuela) and Verificado.mx (Mexico) and Spain (Maldita.es) for the study of the circulation of disinformation.

How do we know that content is circulating at the same time in several countries?

Maldita.es has designed a centralised system that acts as a repository through which fact-checkers can send the content they receive through their respective chatbots or that which they identify on the internet, in accordance with the methodology established for this project. If the content circulates in one or more countries, an alert is sent to the rest of the countries so that they can check if the disinformation is circulating in those countries and, if so, they indicate it in the shared system. Just because disinformation has been seen in a country does not necessarily mean that the fact-checking organisation publishes the verification, as it may not have been viral enough.