“Krym – nash! Crimea is ours!”

This was the slogan Russian authorities used for celebrating the annexation of the Ukrainian peninsula – a process which started five years ago, in February 2014.

Since then, the Crimean question has not only been a struggle over territory; the annexation also laid the ground for a struggle over truth, which remains until this day.

Polite and green men

Heavily armed and stripped of their insignia, Russian soldiers quietly took control over Crimea’s infrastructure in the turbulent days that followed Ukraine’s Maidan Revolution.

In Russia, these soldiers became known as “polite people;” outside of Russia, they were “little green men.” Both nicknames played on their deniability, i.e. the fog of falsehood that surrounded the Russian military operation.

From its very start, the annexation of Crimea has first and foremost been a disinformation campaign.

Challenging disinformation with reporting

The eyes and ears of the outside world were the reporters who worked on the ground in Crimea. As the events accelerated, they would play the leading role in challenging the Kremlin’s disinformation.

Among them was journalist Simon Ostrovsky, who day after day described developments for Vice News with a series of video reports; his award-winning work has become a modern classic.

Click to watch Simon Ostrovsky’s original reporting for Vice News with the ‘little green men’ invading Crimea

With Ostrovsky’s help, international audiences witnessed upfront the decisive encounters between Ukrainian and Russian servicemen. He showed who the real people were on both sides of the conflict – and made the Russian masks fall.

Without professionals like Simon Ostrovsky in the right place at the right time, the Kremlin’s disinformation campaign could potentially have been more successful than it turned out to be.

Strategically challenging disinformation

The events in Crimea did not only attract the attention of the important here-and-now hotspot reporters.

A number of more strategic and long-term initiatives also appeared as a response to the disinformation campaigns surrounding Crimea and Donbas in eastern Ukraine.

The Kyiv-based online project StopFake quickly became an international trend-setter in the practice of raising awareness through compiling examples of pro-Kremlin disinformation and storifying these observations with feature articles.

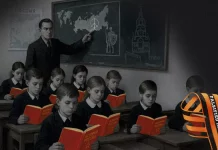

“I realised that in the struggle between journalism and disinformation, journalism was losing. For me, as a journalist, it was a moment of personal mobilisation,” StopFake co-founder Yevhen Fedchenko recalls (here among his StopFake colleagues, wearing a red sweater).

In Russia, the independent online outlet The Insider has systematically been challenging disinformation since early 2016. Numerous stories have described cases when events in Crimea and elsewhere have been manipulated to fit the Kremlin’s narrative.

There have also been international efforts to directly push back on pro-Kremlin disinformation; among the examples are the EU’s EUvsDisinfo project; the Atlantic Council’s DFRLab; RFE-RL’s Polygraph and the online outlet Coda – whose investigations team Simon Ostrovsky now leads.

Coda also has a Russian edition led by the Russian journalist Alexey Kovalyov, whose blog “Noodle Remover” was another important centre for exposing the Kremlin’s disinformation in the aftermath of Crimea’s annexation.

Crimea is not Russia

Five years into the annexation, Crimea is still not “nash,” still not “ours,” still not a part of Russia. Insisting on that is to disinform, and repeating the slogan does not make it happen.

It is thanks to Simon Ostrovsky’s and his colleagues’ reporting from the heart of events that we could distinguish false from true in real time.

And it is thanks to the long-term work of, among others, Stop Fake, The Insider and Coda that the world has learned a new word – ‘disinformation’ – and is better prepared not to fall into the trap of believing that the game is over and Crimea is Russia’s.