By Thomas Kent, for CEPA

What to do when a sudden event happens, facts are lacking and disinformation starts to spread?

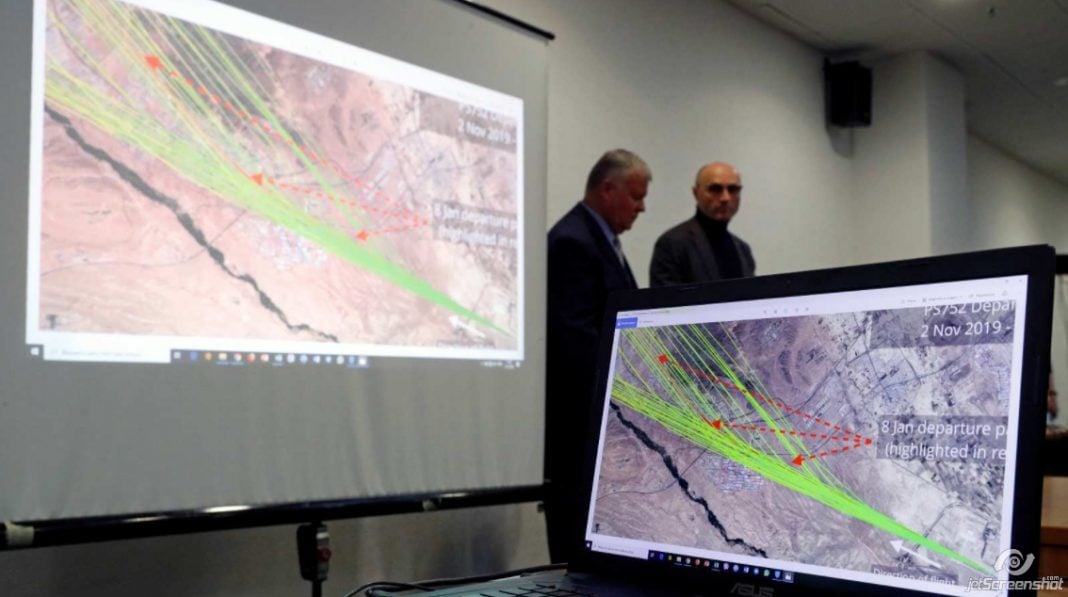

On the morning of January 8, 2020, Ukrainian International Airlines jet crashed minutes after takeoff from Tehran’s international airport, killing 176 people.

Why did the plane go down? In the first hours after the disaster, there was no obvious answer. There had been no radio transmissions reporting a fire on board, no radar data showing a failure to climb, nothing that offered an immediate explanation.

To the world, the cause of the disaster was, essentially, unknowable. Ukraine’s president, Volodymyr Zelensky, rightly warned against “speculation or unchecked theories” pending an official investigation.

Yet by nightfall the same day of the crash, a Russian news agency was headlining speculation, based on “too-suspicious coincidences,” that the plane was shot down by a U.S. drone aiming for an Iranian plane. Some on Twitter opined that Iran had shot down the Ukrainian jet (which eventually turned out to be right). But much of the online churn blamed the United States, which had just assassinated an Iranian general and sustained an Iranian missile strike on its troops in Iraq.

The torrent of speculation over what brought down the plane highlighted the extreme vulnerability of the information environment in the first critical hours after an unexpected news event.

Reports by responsible media saying simply that “authorities are investigating” are thin gruel to people who expect their news needs to be instantly gratified. They will relentlessly trawl social networks and search engines, eagerly consuming whatever speculation is out there. And as many academics have found, the first claims they encounter may lodge solidly in their minds, resisting even the most authoritative explanations that later come to light.

Disinformation artists relish moments like these. They have a ready store of pet disinformation themes that they can instantly adapt to whatever has just happened. In an information vacuum, almost any event can be twisted to cast doubt on Americans, George Soros, the European Union, or some other favorite bugbear. And if the narratives they launch prove wrong? The outlets that disinformation actors often use to spread their content — suddenly-created news brands and internet sock puppets — can easily be replaced. There is no long-term integrity to protect.

In contrast, Western governments and mainstream media feel bound by their reputations. Many quality news outlets pride themselves on not touching rank speculation with a 10-foot pole — although such policies are eroding under the pressure of commercial competition and the 24-hour news cycle. Governments feel a heavy responsibility to be certain of everything they say. Alex Aiken, executive director for UK Government Communications, says “acting before you are in full possession of the facts” is one of the greatest dangers government communicators face.

But what to do when a fast-moving news story demands some kind of reaction to head off potential disinformation, even though essential facts are lacking?

The best strategy is to have anticipated disinformation and prepared for it. When NATO troops staged exercises in Lithuania in 2017, a rumor appeared that German soldiers had raped a teenager. Lithuania and NATO, which had expected an information attack against the German forces, reacted immediately with a declaration that the claim was false and the work of the Russians. Even better would have been a public campaign ahead of the exercises, warning citizens to expect false narratives and promoting an official “rumor control” website. (To Lithuania’s credit, it has long run general campaigns against Russian disinformation.)

But events like a Ukrainian airliner crash can happen out of nowhere. Simply recommending that people be patient is to abandon the information sphere to professional disinformers.

Here are some possible tactics in such situations:

- Highlight the sheer range of speculation as an argument for people to keep an open mind. This can encourage journalists to write their stories as a “truth sandwich.” Instead of starting a story with a questionable narrative – which puts that claim into the headline – a “truth sandwich” would start by emphasizing that the facts are unknowable. The story would then cite some examples of speculation (the more bizarre and contradictory the better), and finish up with the best estimate of when the truth might be known. By noting how random and contradictory the speculation is, governments and responsible journalists may be able to keep any one false narrative from gaining traction.

- Do the maximum to report what is known. Any country concerned about disinformation about the Ukrainian flight could have held a well-publicized “here’s-what-we-do-know” briefing, with aviation and military experts running through a variety of possible, reasonable explanations. (Experts hate to speculate, but this would be for a good cause.) The bottom line of the briefing would still be “wait and see,” but the quick appearance of experts, brandishing whatever technical data was initially available, would have provided an immediate outlet for public and media questions and reinforced the value of official sources.

- Speed the release of information that is highly likely to be true, on a conditional basis. According to Aiken, it took 13 days for the UK government to reach a formal, publishable conclusion that Russia poisoned Sergei Skripal and his daughter in 2018. But within 48 hours of the attack, then-Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson told Parliament, “We don’t know exactly what has taken place in Salisbury, but if it’s as bad as it looks, it is another crime in the litany of crimes that we can lay at Russia’s door.” British media reported at the time that Johnson’s comment was hardly random, but based on preliminary intelligence conclusions. His statement focused news outlets, which had been wavering over whether the Skripals were the victims of a Russian attack or a drug overdose, on the action by the Kremlin.

In the same vein, American, Canadian, and UK sources began leaking anonymous word two days after the Ukrainian crash that it was “highly likely” Iran had shot it down. A statement by a named official along the lines of Johnson’s regarding the Skripals would have been even stronger. (Iran officially confirmed it shot the plane down on the third day after the disaster.)

Sudden, newsworthy events that cannot be immediately explained always provide juicy targets for disinformation artists. Some of these strategies can help to mitigate the damage until the full facts are unearthed.

Unfortunately, Western governments are often slow to respond to speculation and disinformation even when they have all the facts. Experts often say responses to false narratives must start within 2-3 hours to be effective. But the process of issuing government statements, often requiring signoff by multiple senior officials and declassification of sensitive information, can make reacting at this speed a daydream.

Non-government organizations may be helpful. Lithuania’s “elves,” a civil society group that is believed to include some government employees, sometimes starts fighting false narratives before the government can issue official statements. In several other countries, non-government activists have their own platforms and tactics against disinformation.

How these capabilities are deployed against false narratives in their first hours will likely make the difference on whether those narratives succeed.

By Thomas Kent, for CEPA

Thomas Kent – a specialist on disinformation and journalistic ethics, is a former president of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. His book, “Striking Back: Overt and Covert Options to Combat Russian Disinformation,” was published in September by The Jamestown Foundation.

Photo: A map of flight PS-752’s departure paths is seen on a computer screen at a news briefing about the crash of the Boeing 737-800 plane, flight PS-752, on the outskirts of Tehran, at the Boryspil International Airport, outside Kyiv, Ukraine January 11, 2020. Credit: REUTERS/Valentyn Ogirenko

Europe’s Edge is an online journal covering crucial topics in the transatlantic policy debate. All opinions are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the position or views of the institutions they represent or the Center for European Policy Analysis.