By DFRLab

On March 18, Russia held presidential elections, widely expected to re-elect Vladimir Putin to a fourth presidential term by a wide margin.

With Putin’s victory a foregone conclusion, attention focused on state efforts to bolster turnout, as @DFRLab has already reported. During the day, however, over 2,000 separate reports of electoral violations also surfaced, including “carousel” voting, voter intimidation, ballot-stuffing, and attempts to remove observers from polling stations.

Boosting turnout

A continuation of pre-election efforts to boost turnout occurred throughout voting day. According to an investigation published by “MBH Media”, an online page backed by Kremlin opponent Mihail Khodorkovsky, the presidential administration and Russia’s current ruling party, “United Russia” (Единая Россия), issued instructions on how to mobilize the staff of government corporations with the aim of providing “practically 100% participation of employees of enterprises / institutions of the corporation, their families and veterans in the March 18 elections.”

Such measures would not be illegal, as long as they were not accompanied by instructions on whom to vote for, but they underline the state’s desire to boost turnout as much as possible.

Footage of apparent attempts to mobilize large numbers of state employees — including police and soldiers — quickly began to circulate online.

A YouTube user from Belogorsk published a video showing hundreds of men in military uniforms at a polling station.

“Fair elections. Well well.” (Source: YouTube / Роман Stix)

The video was included in a report by independent Russian media outlet TV Rain. As well as soldiers, the video showed students from the maritime university in St. Petersburg lining up to vote.

Source: YouTube/ TV Rain)

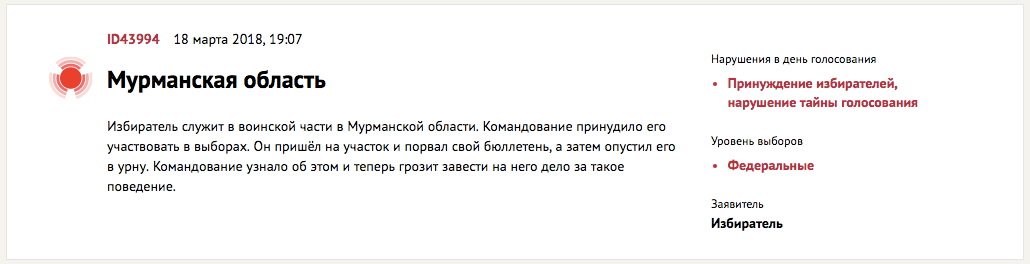

Online reports suggested that not all these voters took part willingly. According to a nationwide list of reported violations managed by the “Golos” (Голос, “Voice”) electoral transparency group, a voter in the northern city of Murmansk, who was a member of the military, complained that he had been ordered to go and vote, then threatened when he spoiled his ballot.

By 17:00 UTC on March 18, the site listed over 2,400 reported violations, of varying degrees of gravity.

In Volgograd, the team of anti-corruption campaigner and opposition leader Alexei Navalny, who has been barred from standing and who called for a boycott of the vote, published a video showing a bus bringing students to a polling station.

Source: YouTube / Штаб Навального в Волгограде)

Earlier, on March 13, a local TV channel in Volgograd reported that both public and private public transport providers in the city had volunteered to bring citizens to the polling stations for free.

Source: YouTube / ВЕСТИ35.РФ)

A news agency in Tyumen oblast published a video showing a bus driver admitting that he was bringing people to a polling station.

Source: YouTube / Информационное агентство ТюменьPRO)

Despite these efforts, reports of turnout varied. Midway through election day on the afternoon of March 18, Navalny said that observers from his team had registered a turnout of between 12 percent and 25 percent lower than officially reported figures in Perm, the Altai Republic, and Kemerovo.

Алексей @navalny заявил, что официальные данные о явке завышены на 12-18% по сравнению с информацией от его наблюдателейhttps://t.co/bRP9SbgAZh pic.twitter.com/Tbff5Mfijw

— Настоящее Время (@CurrentTimeTv) 18 марта 2018 г.

Final figures had not been published at the time of this report, but debate over the actual turnout is likely to continue well after the election.

Evidence of election rigging

As in previous cycles, this year’s presidential election was marked by numerous reports and claims of vote rigging. Judging by the available videos, the most frequent method of rigging votes this year was ballot stuffing.

The sheer quantity of footage showing such violations was troubling on two counts. First, ballot stuffing was arguably the most blatant form of election manipulation, especially when polling stations were fitted with cameras. Second, in many cases, Electoral Commission representatives appeared to commit the election fraud themselves.

For example, YouTube user Dima Vasilev, a new user whose first video was uploaded on the day of elections on March 18, published 18 videos showing evidence of ballot stuffing. The videos were taken all over Russia: Moscow, Tyumen, Chechnya, Makhachkala, Kazan, Irtkutsk, Krasnodar, Primorskiy Krai, and elsewhere.

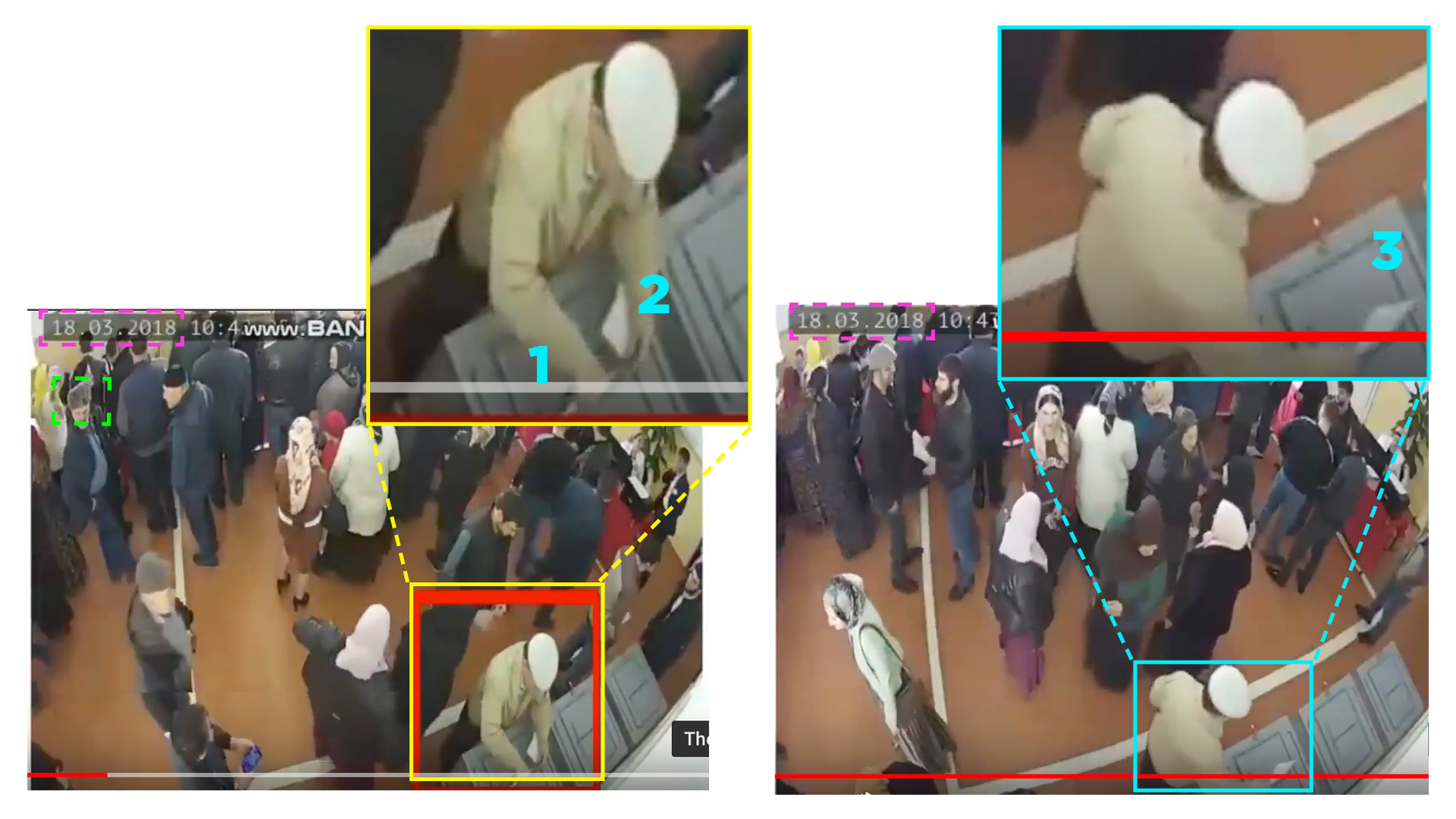

The below video gives an example of ballot stuffing, apparently in Chechnya. The exact location is not known, but the title claimed it to be Chechnya, and the traditional headwear of men suggested this claim to be true.

Source: YouTube / Дима Васильев)

A man was recorded stuffing multiple ballots in one go and then returning after a few minutes to insert one more. According to a reverse image search, this video was not posted before and the camcorder time on the top of the video confirms that this video was taken on March 18, 2018.

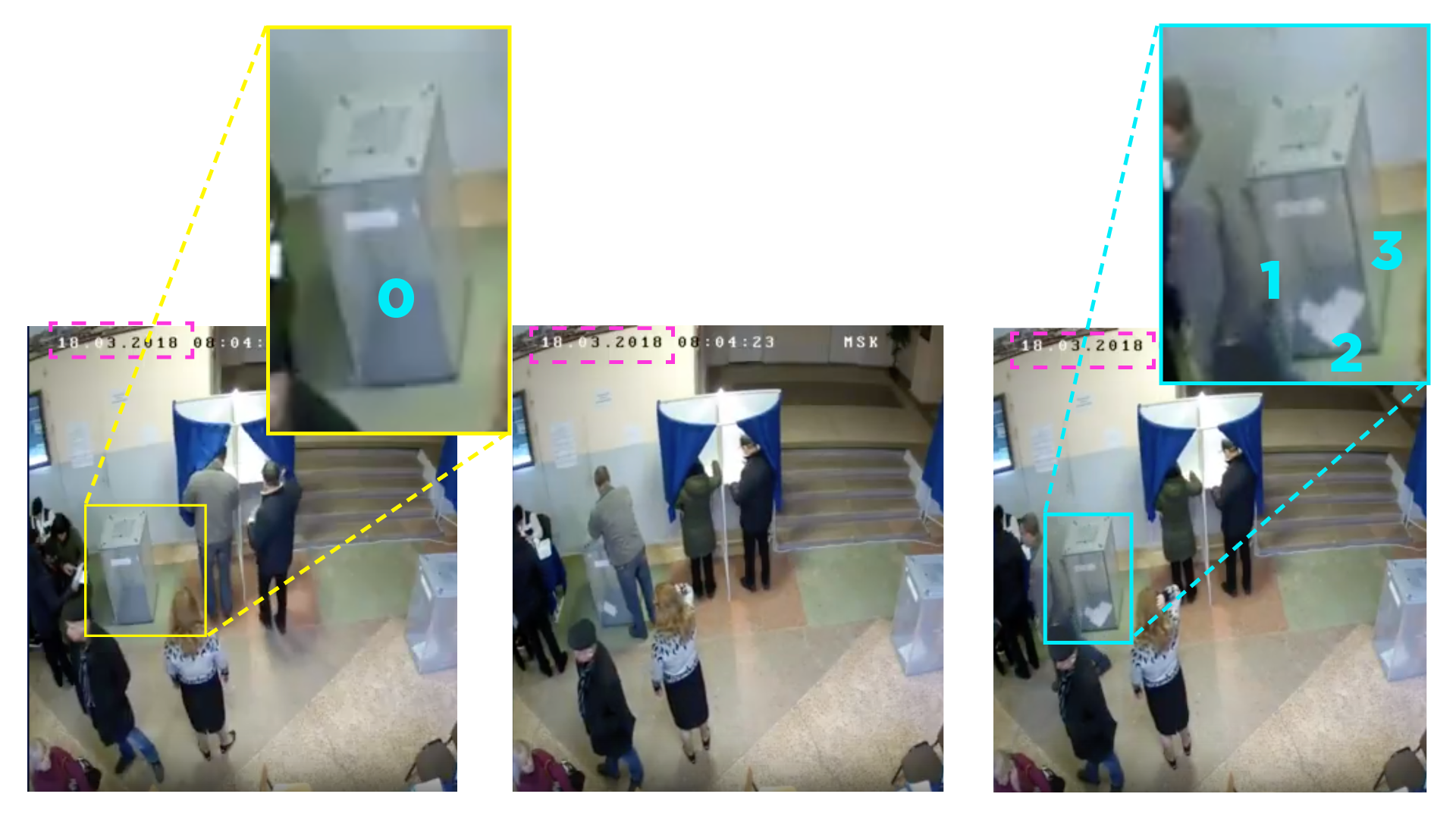

Another example of ballot stuffing was captured by a different user in Rostov on the Don. A man in a gray jacket appeared to drop in at least three ballots in one go. Checking the stills of the footage, we can see that the transparent box is empty as the man stands in a booth. As he walks away, at least three ballots are visible inside the box. The date on the camcorder confirmed the date to be March 18, 2018, and the video was not posted before.

Meanwhile in Moscow, a woman appeared to be working at her leisure as she dropped one by one into the ballot box. Given her calm, it was likely that she was a representative of the Election Commission and felt that she was not being watched. In the video, at least three ballots were added and the woman held a bunch more. A reverse image search suggested the video was genuine.

In another voting poll in Moscow, Election Commission representatives worked as a team to fill the urns. In the video, two ladies issued the ballots and two ladies stuffed them in the box. The camcorder date confirmed the date to be March 18, 2018.

Within hours, the Moscow suburban electoral commission confirmed that the violation had taken place, the perpetrators had been fired, and all the votes in the violated urn had been declared void.

Further evidence of election rigging was posted on YouTube by a user named Irren Klaius, at 09:14 (UTC) on March 18. A woman and a man walking past a polling station found 18 marked election ballots thrown out into trash. The video title and the woman narrating the video claimed that all the ballots were marked as supporting Putin.

Source: YouTube / Irren Klaius)

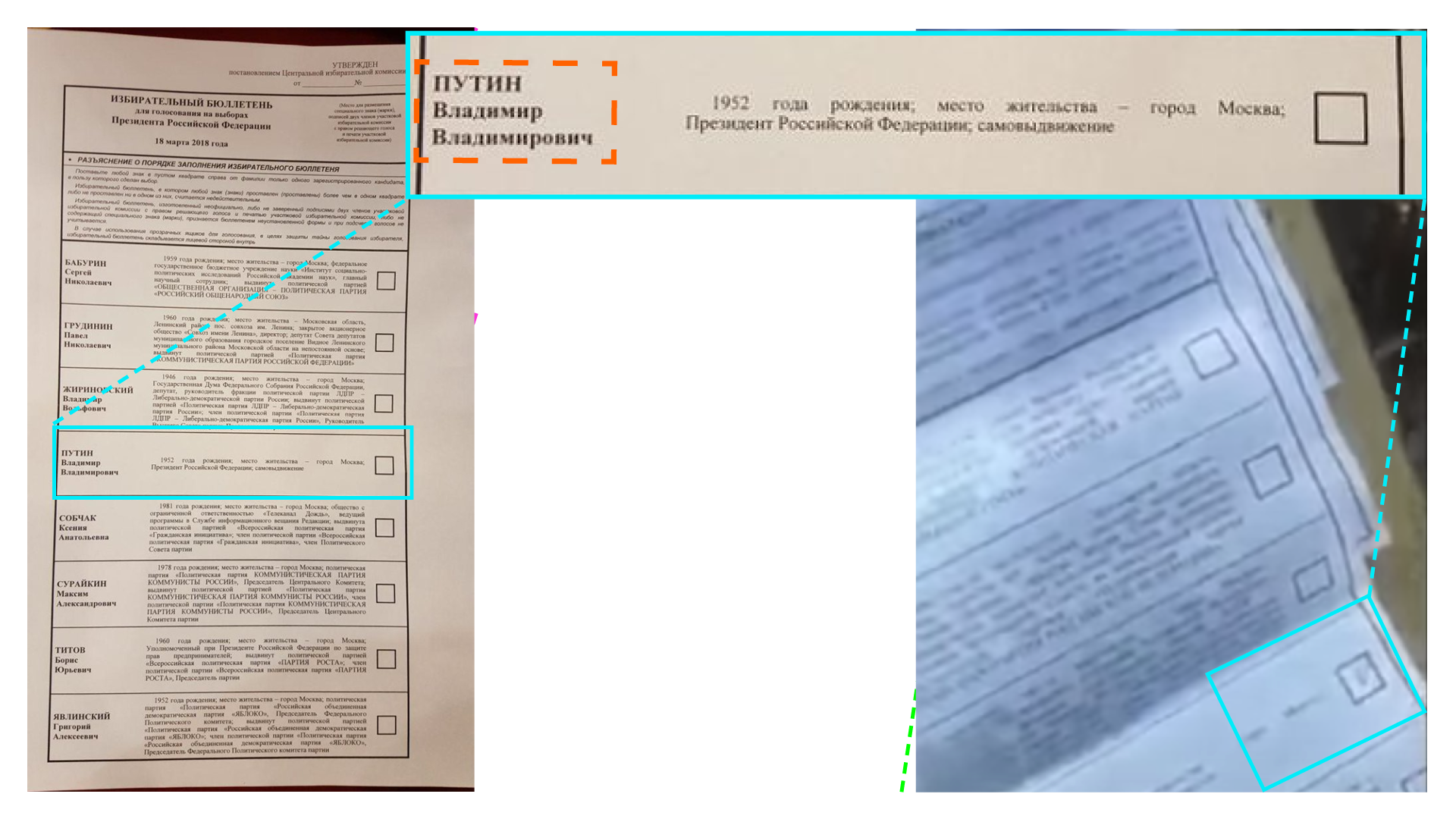

After inspecting the video footage, @DFRLab confirmed that the ballots were genuine — the date was March 18, 2018 and all of them had the official stamp of Central Election Commission of Russia with a holographic mark.

Furthermore, comparing the marked ballots in the video with the photo of an official list of candidates, we concluded that they were marked to support Vladimir Putin (choice no.4).

Navalny’s team even made a compilation of various election rigging incidents this year. As humorous as the video was — with its cheerful music and accelerated movements — the scope and diversity of locations and the cynicism of the people committing these frauds was alarming.

(Source: Twitter / @CurrentTimeTV)

Here is a short list of other examples of election fraud recorded during the 2018 Russian Presidential election: Dagestan, Moscow, Tyumen, Krasnodar, Primorskyi Krai.

Who will observe the observers?

Pressure has also been put on representatives of civil society seeking to observe the elections, according to journalists and observers on the ground.

According to the Golos list of violation reports, 214 violation reports — roughly 9 percent of the more than 2,400 submitted by 17:00 UTC on March 18 — concerned interference with election observers.

The complaints varied from unhelpful officials to physical violence. In St. Petersburg, for example, an unnamed observer complained that an election official had refused to let him see the voters’ register. The Golos website indicated that a formal complaint had been made.

In Saratov, the Golos website shared a video filmed by local station Free-News Volga (fn-volga.ru) that showed a polling station official refusing to let a film crew move freely in the station. When the journalists argued that such a restriction was unlawful, the official called a policeman, who threatened the journalists with physical force (timestamp 1:35 on the video).

Source: YouTube / fn-volga.ru)

In Makhachkala, in the southern republic of Dagestan, a mobile-phone video in a polling station appeared to show a combination of intimidation and ballot-stuffing. The video showed a group of unidentified men clustering around an apparent election observer.

Source: YouTube / kartanarusheniy.org)

A longer video appeared to show the sequel, with the observer, shouting for the police, being taken away. While this was ongoing (timestamp 1:50), an unidentified man appeared to place a number of ballots in the urn; soon after (from timestamp 4:16), a woman apparently working in the polling station did the same.

Source: YouTube / kartanarusheniy.org)

Also in Dagestan, the Financial Times’ Max Seddon reported seeing a group of up to 40 men dragging an election observer away, using enough force to leave visible bruises on his arm.

Zukhrab Omarov, 28, an election observer in Dagestan, tried to complain about the sudden appearance of 40 goons at his polling station, whom he suspected were part of a “carousel.” They dragged him outside in full view of the cops and beat him up pic.twitter.com/1obWCSMpIn

— max seddon (@maxseddon) 18 марта 2018 г.

Seddon then reported the same group dragged observers away from a nearby station, apparently without the same degree of force. Judging by the video which Seddon retweeted, this post refers to the ballot-stuffing also reported by Golos.

Was just at this polling station in Dagestan. A gang of goons who had just beaten u the observers next door ran in and dragged the monitors out of sight of the ballot box. The polling workers then stuffed the ballot box before he came back. https://t.co/K7tO7EptxT

— max seddon (@maxseddon) 18 марта 2018 г.

In Sevastopol, in the Crimea, annexed by Russia in 2014 despite widespread international condemnation, independent news station TV Rain reported that one of its cameramen, Vladislav Pushkarev, had been turned out of a polling station and threatened with force, after being accused of not holding the correct documentation. According to Rain’s chief editor, Pushkarev held a valid accreditation from the Central Electoral Commission, but was told that this was insufficient.

Navalny’s team manager in Siberia, Oleg Snov, tweeted that observers from the liberal Yabloko party in Kemerovo, Siberia, had largely been blocked from attending the polls.

Массовые недопуски наблюдателей в Кемерово. Напомню, Яблоко отозвало дов. лицо и, хотя направления выданы до этого и имеют юридическую силу, комиссии пытаются массово не допустить людей.

Мы успели подстраховаться и с утра @ks_pakhomova выдает новые направления всем недопущенным.

— Олег Снов (@olsnov) 18 марта 2018 г.

His colleague, Ksenia Pakhomova, tweeted a video of a polling station guard, who said that the observers had been advised to go to the Kemerovo city hall to get new permits and then come back if they were allowed.

Нашим наблюдателям предлагают пойти в администрацию города #Кемерово , потому что она уполномочена решать вопрос об их удалении с участка. Я не шучу. “Если они разрешат, то вернетесь” #забастовка #Кузбасс https://t.co/kpft02QFRR

— Ксения Пахомова (@ks_pakhomova) 18 марта 2018 г.

The leader of the Navalny organization’s legal team, Ivan Zhdanov, tweeted that similar steps had been taken in the Khabarovsk district, and that in Komsomolsk on the Amur, all of Yabloko’s observers had been blocked.

Началось. Массовый недопуск наблюдателей в Хабаровском крае,под предлогом, что неправильно Яблоко направление выдало (подписаны неуполномоч. лицом). Яблоко говорит, что все правильно. Подпись и печать председателя отделения. Пишем жалобу и организуем выдачу других направлений.

— Ivan Zhdanov (@IoannZH) 17 марта 2018 г.

Translated from Russian: “It’s begun. Mass prohibition of observers in the Khabarovsk region, on the pretext that Yabloko did the authorization wrong (signed by someone who wasn’t authorized). Yabloko says that it did everything right. Signature and stamp of the chair of the local team. We’re writing a complaint and organizing a handout of new permits.” (Source: Twitter / IoannZh)

В Комсомольске-на-Амуре на этом основании не допустили всех наблюдателей

— Ivan Zhdanov (@IoannZH) 17 марта 2018 г.

Spoiling ballots

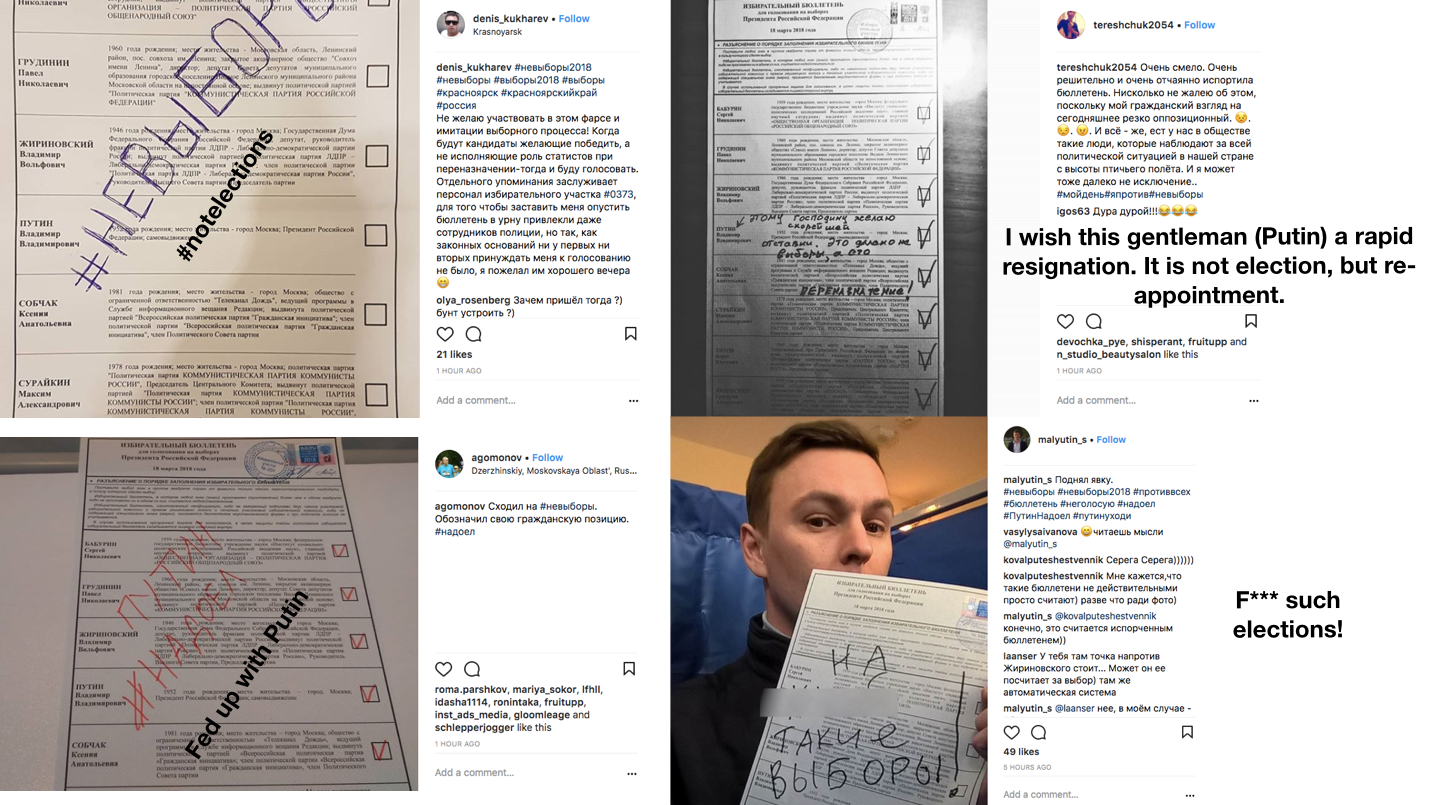

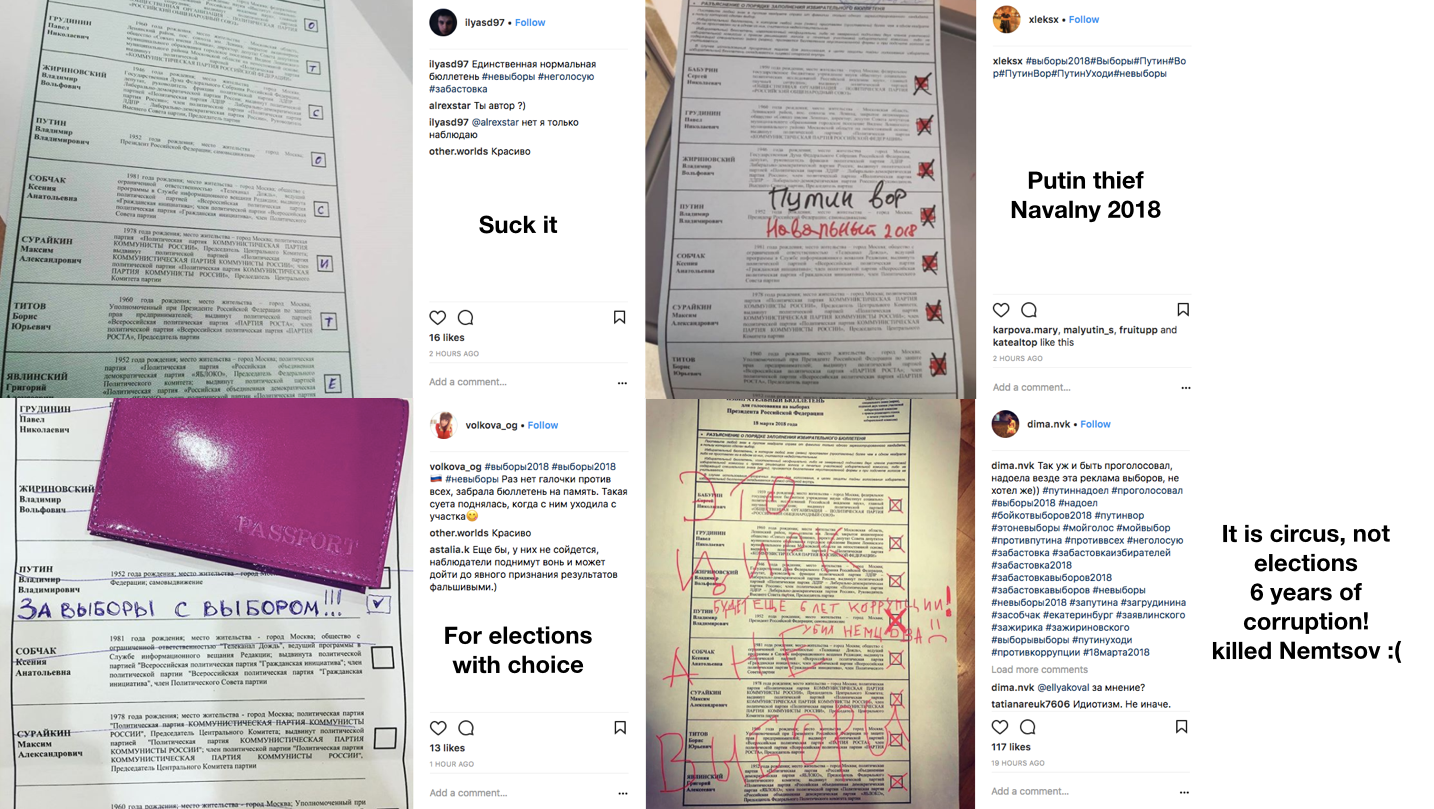

Some voters appeared to have responded to the pressure to go vote by turning up, and spoiling their ballots, like the unnamed Murmansk serviceman described above.

Putin critic and one-time challenger Khodorkovsky spoilt his ballot, and posted about it online.

Тех, кто думает, что явки не будет – огорчу: не придет часть наших сторонников. Путинисты вас не слушают. Важны голоса «против» в сети с геотегом. pic.twitter.com/ozuvRWJol0

— Ходорковский Михаил (@mich261213) 11 марта 2018 г.

Some Instagram users followed his example and posted images of their spoilt ballots online.

Conclusion

Local and foreign observers have reported literally hundreds of violations, of varying types and degrees, from across Russia.

Much of the activity appeared to have been focused on getting out the vote; some appeared, more directly, to involve ballot-stuffing and attempts to inconvenience or sideline the observers who might have revealed it. Some were committed by Electoral Commission staff themselves.

These attempts are noteworthy for the unease they betray in Russia’s ruling party and bureaucracy, given the long-term efforts the government has made to render elections controlled and predictable, such as jailing opposition leaders and imposing state control over the main TV stations.

The efforts to galvanize voters appear, from the MKH reports and the plethora of electoral advertising, to have been centrally driven, and reflect a concern with the turnout which will be the best indicator of Putin’s actual popularity.

The local ballot-stuffing may have been more a question of local initiative, although the full picture remained unclear at the time of this report. Nevertheless, it, too, seems to betray a lack of confidence in the system, and a lack of faith in Russian voters’ desire to vote for the same leader they have had, as either president or prime minister, for 18 years.

The efforts do, however, illustrate another point, and that is the courage, and dedication to transparency, of Russian voters. The vast bulk of the online material revealing cases of electoral violations came from Russian users. Many — such as the Navalny team — posted their evidence under their own names; thousands, across the country, entered polling stations with cameras and mobile phones to record what was going on.

There is no doubt that Putin will be declared the winner of Sunday’s election; it is greatly to the credit of Russian civil society that so much will be known about the manner of his victory.

By DFRLab

Ben Nimmo is Senior Fellow for Information Defense at @DFRLab.

Follow along for more in-depth analysis from our #DigitalSherlocks.