By Darko Brkan, for Power 3.0

Disinformation has never been more a part of the public discourse in the Balkans and Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH) than in recent years. However, knowledge of the methods, sources, motives, connections, actors, and other aspects of the disinformation landscape in BiH and the region is scarce, based mostly on anecdotes and some research about the country’s media scene.

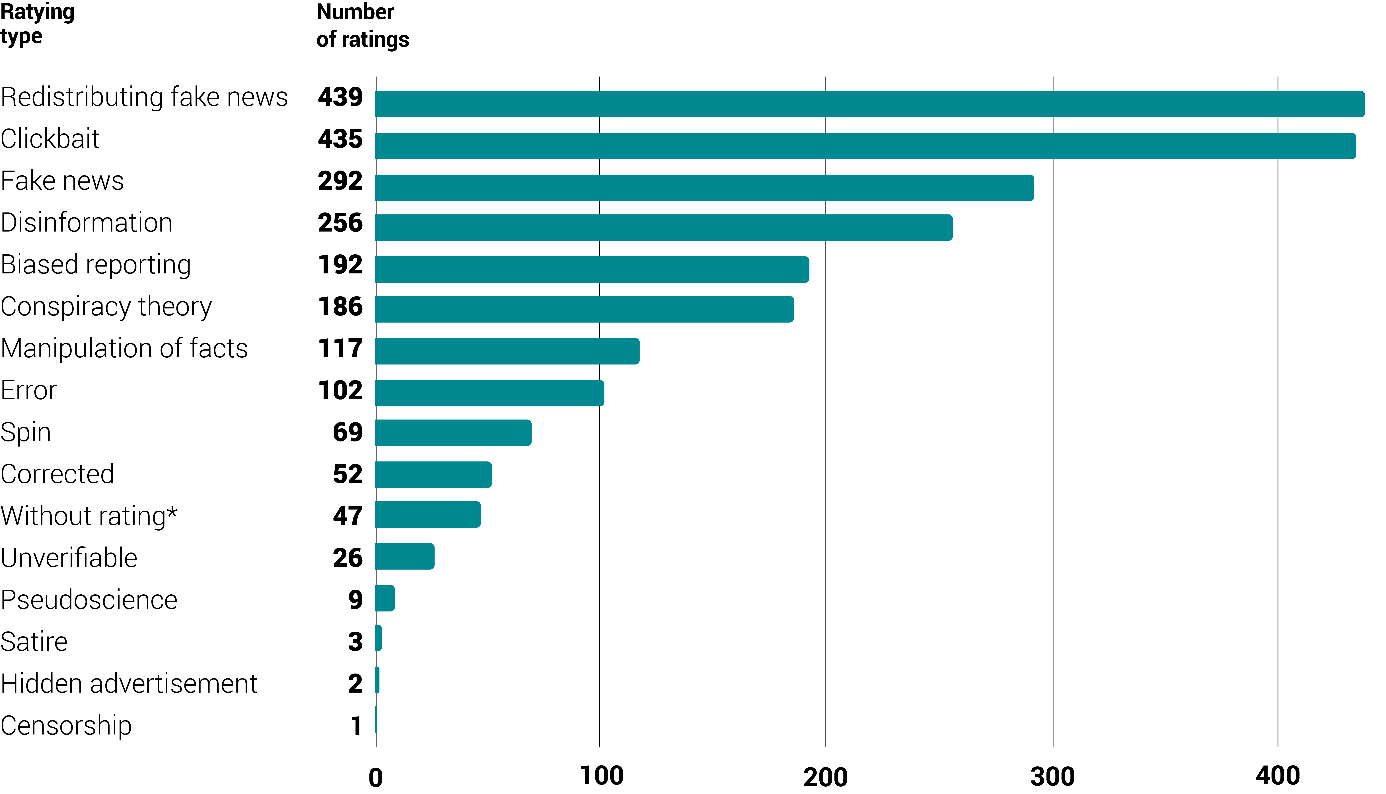

With this in mind, Raskrinkavanje.ba, an online disinformation-debunking portal run by Civic Association “Why Not,” analyzed disinformation in BiH based on 2,420 media articles published by 752 media outlets that were fact-checked between November 2017 and November 2018. These articles were “rated” (or classified) as being one or more of fourteen forms of media manipulation, producing 3,592 different ratings. More than 60% of the articles that were rated as false or misleading—1,486 articles by 477 media outlets—dealt with issues that are political in nature.

The research looked into the types, sources, and redistributors of disinformation; their geographic location; their targets and beneficiaries; and the ways in which connections between them serve as distribution channels for disinformation. It found that while most sources of disinformation in BiH are domestic, a tightly knit hub of foreign outlets disproportionately uses a variety of disinformation tactics to push a counter-democratic agenda in the country.

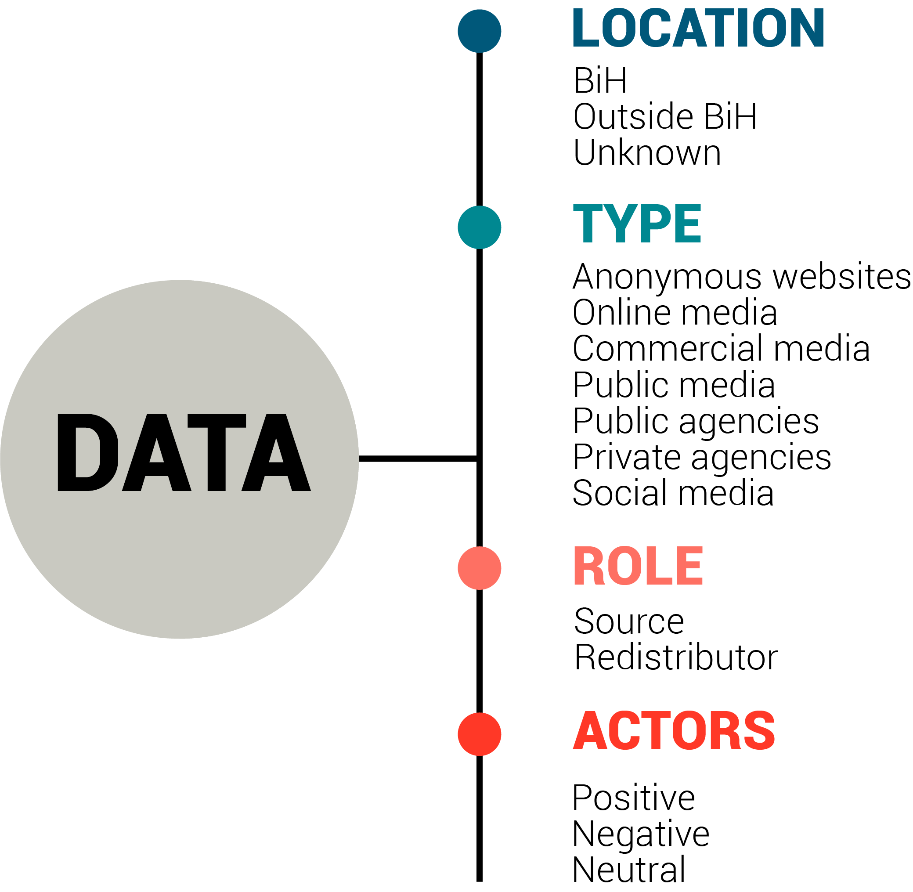

Figure 1 — Methodology: Categories of information sources captured by the sample

Of the political disinformation analyzed, intentionally fabricated information was the most common type. This category includes “fake news” and “redistributing fake news” and amounted to a third of all ratings in the sample—followed by “clickbait,” which was responsible for one-fifth. Overall, articles with political motives outnumbered those published by “opportunistic disinformers” (websites aiming to make a profit from clickbait and user traffic), suggesting that even if anonymous portals are the most common sources and redistributors of disinformation, political and state actors have a clear political agenda and are more organized.

Figure 2 — Articles in the research sample rated by category:

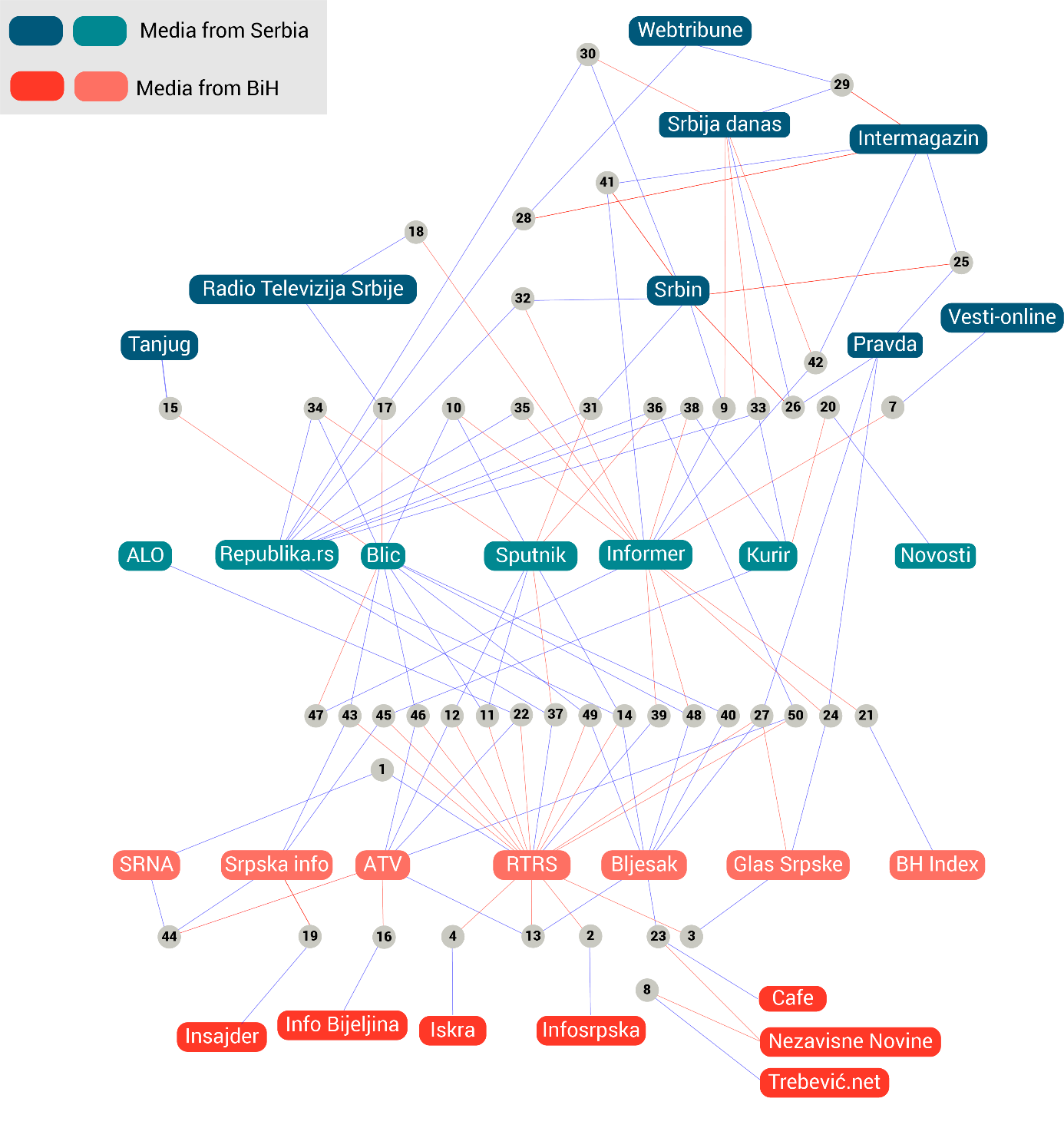

This thesis is confirmed by the connections between different media outlets publishing the same disinformation. Apart from a couple of smaller clusters, this research observed the existence of one big disinformation hub. Most of the media outlets for which the research established structured connections were not anonymous and their disinformation had a clear political agenda; some of them were even public broadcasters and state news agencies, including for instance the public broadcaster of Republika Srpska, RTRS, which with 124 ratings was by far the most-rated outlet in the sample.

The twenty-nine outlets comprising this hub used each other as sources and redistributors of disinformation in order to negatively influence public opinion on both domestic and geopolitical issues, especially those regarding the United States and NATO. While most sources in the sample were based in BiH, an alarmingly high number of media from neighboring countries were also present via connections with BiH-based media outlets. Of the twenty-nine media outlets in the hub, fifteen were Serbian (out of the twenty biggest foreign producers of disinformation in Bosnia, eighteen are from Serbia), and fourteen were from BiH (out of which twelve were from Republika Srpska).

It is noteworthy that the outlets with the most articles and connections within this hub were the main public broadcaster (RTRS) and public news agency (SRNA) of Republika Srpska. These included Alternativna TV, a commercial media outlet owned by a businessman close to the Republica Srpska government; Informer, a Serbian tabloid; and Sputnik, a Russian state-owned outlet and the only outlet in this hub based outside the Balkan region.

Sixteen Sputnik articles were included in the sample. Each article was rated as including one or more non-mutually-exclusive forms of content from the chart above; these sixteen articles received thirty-six such ratings, making Sputnik among the most frequently rated publishers of disinformation. However, its full presence and impact is even larger, especially in pre-election periods, as mentioned in two analyses published by Rasrkinkavanje.ba in the year leading up to the 2018 BiH elections.

Figure 3 — Connections between foreign and domestic outlets in the main disinformation hub:

A “connection” exists when two outlets publish the same disinformation multiple times. Darker colors represent domestic media connected only to other domestic media. Lighter colors demonstrate stronger cross-border ties. Lines represent relevant connections between outlets, and numbers reflect an algorithmic score of the strength of the connection.

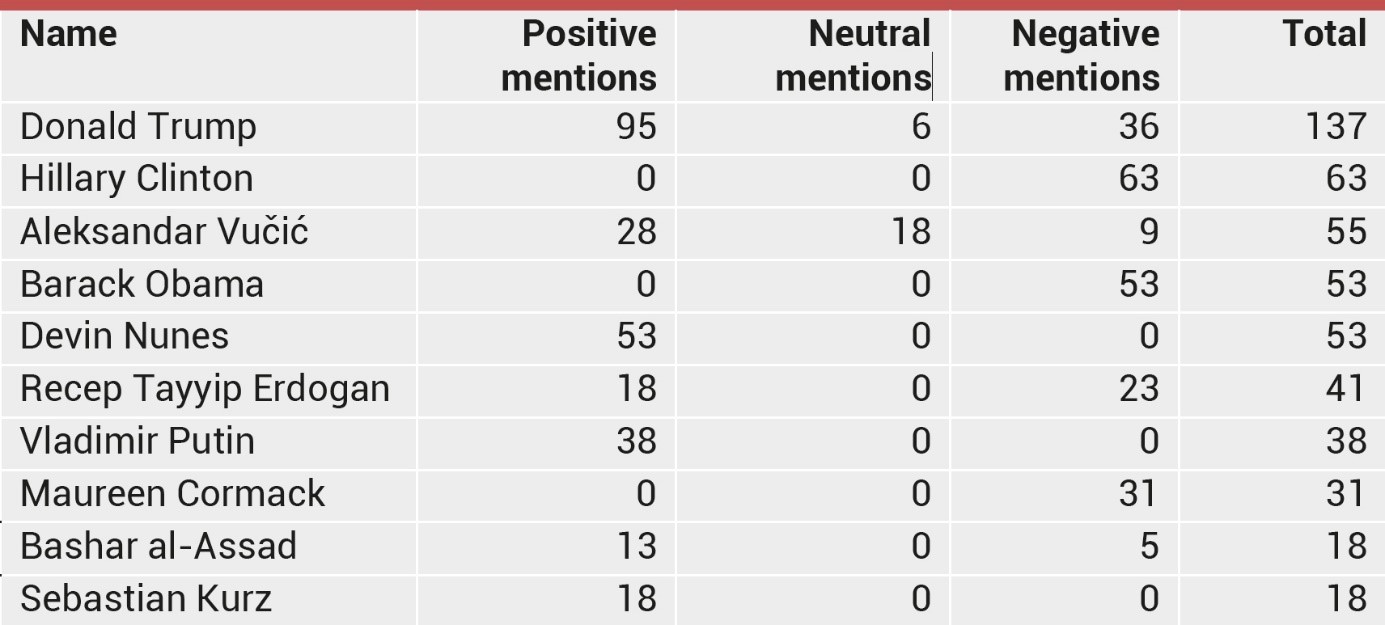

The disinformation from both the hub and the general sample suggests an agenda focused on undermining pro-democratic actors. US political figures, especially those connected to the previous US administration, appear to be the primary targets of disinformation related to international matters produced by the main hub. On the other hand, the content in the sample mostly portrayed Russian government actors in a positive light, while the European Union was mostly presented as a neutral actor or a desirable partner.

Figure 4 — Mentions of political figures in disinformation analyzed as part of the research sample:

Both foreign and domestic disinformation are problems in BiH, and awareness of the challenge there is limited. This research is an important step for developing future action. First, democratic actors need to continue fact-checking and debunking efforts in order to increase awareness, glean insights, and follow trends. Second, since most disinformation narratives have regional reach, regional networking and cooperation is crucial. Third, coordinated engagement with big tech companies must include the Balkans, and these companies should play a role in minimizing the problem. Finally, civil society needs to engage public officials and other stakeholders in developing frameworks for fighting disinformation and improving media literacy, a key facet of public resilience.

By Darko Brkan, for Power 3.0

Darko Brkan is the founding president of Zašto ne (Why Not), a Sarajevo-based nongovernmental organization that promotes civic activism, government accountability, and the use of digital media in deepening democracy in Bosnia-Herzegovina. Follow him on Twitter @darko_brkan.

Power 3.0 explores how savvy authoritarian governments survive and thrive in a globalized information age, and the ways that democracies are contending with this challenge.

The National Endowment for Democracy (NED) is a private, nonprofit foundation dedicated to the growth and strengthening of democratic institutions around the world. Each year, NED makes more than 1,200 grants to support the projects of non-governmental groups abroad who are working for democratic goals in more than 90 countries.

The views expressed in this post represent the opinions and analysis of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the National Endowment for Democracy or its staff.