The World Press Freedom Day has been marked every year on 3 May after it was proclaimed by the UN General Assembly in 1993. In connection with this date, Reporters Without Borders (RSF) publishes the annual World Press Freedom index, which takes the temperature of the issue internationally. In this year’s index, Russia’s position as number 148 out of 180 countries was unchanged compared to last year’s result.

The open letter to Vladimir Putin

Last month RSF published an open letter to Russia’s president, Vladimir Putin, in which the NGO explains in what areas it sees change as necessary in Russia with regards to press freedom. RSF underlines how grave the issue is by stating in the opening of the letter that “the situation has not been as bad as it is now since the Soviet Union’s fall.”

What are the factors that have led to Russia’s low press freedom score? And how are these factors connected to the pro-Kremlin disinformation campaign, which targets foreign states and societies as well as Russia’s own environment?

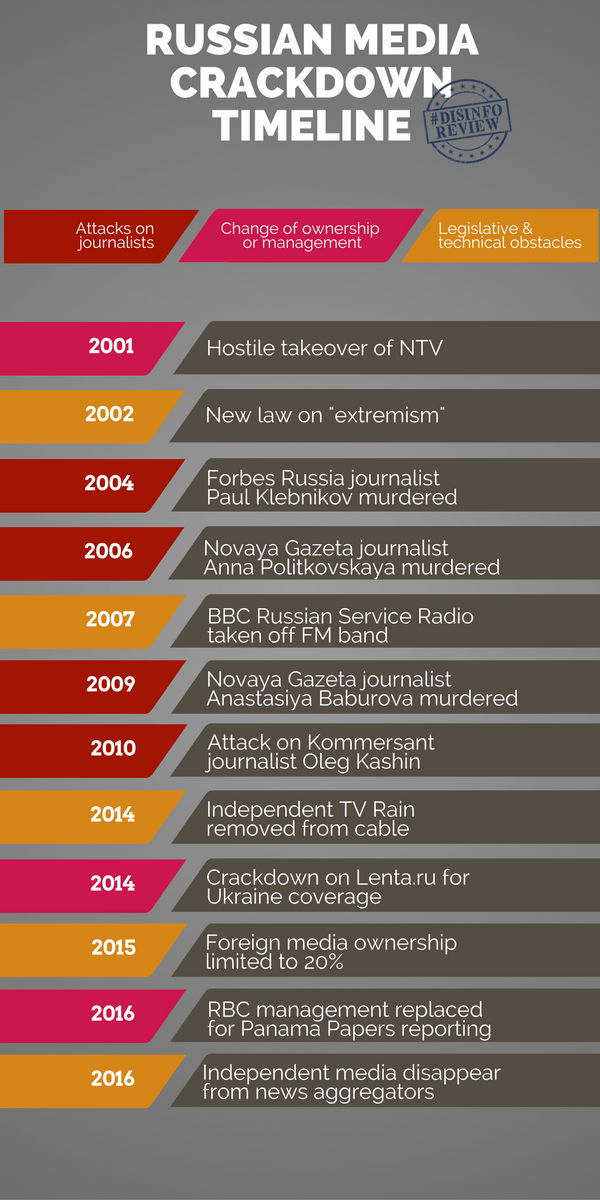

Politkovskaya and other victims of violence

RSF takes note of the fact that “at least 34 media professionals have been killed in connection with their work in Russia since 2000”, and that “in the overwhelming majority of these cases, the investigations have gone nowhere and the masterminds have not been identified.” RSF singles out the independent newspaper Novaya Gazeta which has seen a total of five of its journalists killed, and which “continues to receive threats”. One of the journalists who paid with her life for her journalistic work was Anna Politkovskaya, who was shot dead by contract killers on 7 October 2006. No Russian court has yet clarified who was responsible for ordering the murder. RSF also underlines that “at least five journalists and two bloggers are currently detained in connection with their reporting”.

Five Novaya Gazeta journalists have been killed, including Anna Politkovskaya, who was shot dead on 7 October 2006. Image: Wikimedia Commons

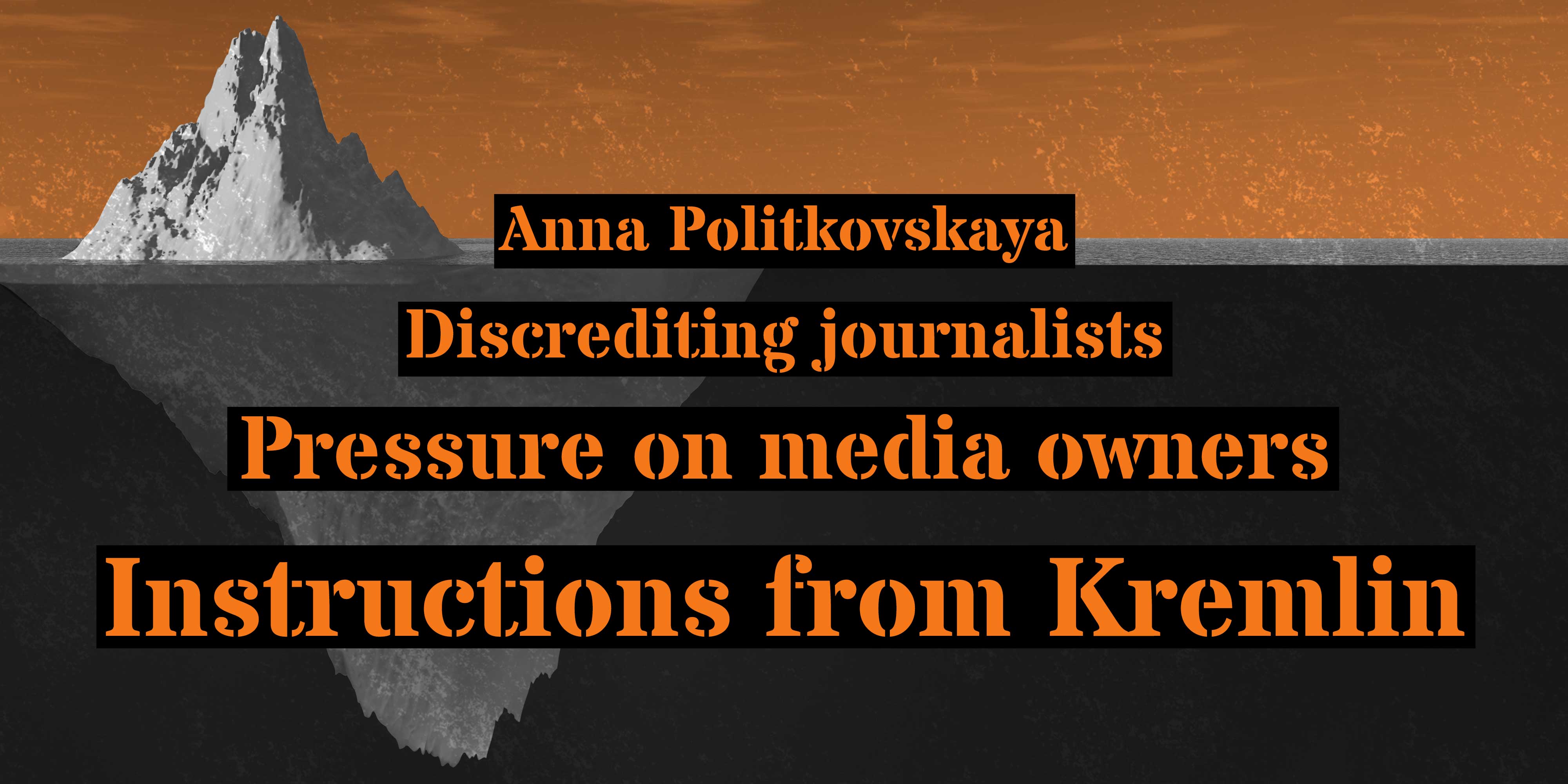

Discrediting journalists and the journalistic profession

On top of the persecution and physical attacks, the journalistic profession in Russia is under pressure from being discredited and harassed by draconic laws; RSF pinpoints specifically the laws against defamation, anti-extremism, ‘offending the feelings of religious believers’ and how their “broad and vague wording allows them to be used selectively and arbitrarily”. With a reference to the infamous Russian law on foreign agents, RSF expresses its concern that the “criminalization of civil society has not spared NGOs that support the media and defend press freedom”.

RSF also describes the overall media environment as dominated by government-controlled TV channels, which “pump out propaganda that fuels a climate of hate and paranoia towards civil society and drags down journalistic standards.” In other words, the very idea that a journalist can be independent is undermined when journalists on the dominating state-controlled TV channels purely act as producers of propaganda, while suspicion is systematically thrown at independent journalists for working as “foreign agents”, i.e. in the interest of foreign governments.

Political pressure on media owners

RSF makes reference to two cases when private media owners have fired chief editors after political pressure. One is the case of the online news portal Lenta.ru whose chief editor, Galina Timchenko, was sacked following the outlet’s coverage of Russia’s war in Ukraine. The other case highlighted is that of another media house, RBC, whose chief editors were fired after the outlet had uncovered ties between the Kremlin and Russians whose names appeared in the Panama Papers. Rather than publicly demanding punishment of the journalists, Russia’s authorities put pressure on RBC’s owner by opening audits against other companies he controlled. It is worth noting that in both these cases, the media in question had become highly successful; a circumstance that would rarely make owners sack top managers in a normal media market environment.

Galina Timchenkol was fired as chief editor of Lenta.ru following its coverage of Russia’s war in Ukraine. She later opened the independent outlet Meduza in Riga together with members of her former Lenta.ru team. Image: Wikimedia Commons

In other words, the Russian government exercises censorship on journalism through punishing private owners if their media do not stick to the propaganda narrative and overstep the government’s red lines. But how are private media in Russia expected to know these red lines?

Instructions from Kremlin: the “temnik” system

The Russian authorities have established a system in which chief editors and key journalists are invited to attend weekly meetings with top managers from Russia’s Presidential Administration. At these meeting, guidelines for the next week in are handed down to the media. It is made clear what should be the narrative for the next week; which topics should and shouldn’t be covered; who should be mentioned positively, who negatively and who should not be mentioned at all. These “briefings” are usually kept as a chain of oral messages, which trickles down from the meetings with the Kremlin to the newsrooms where journalists pitch stories that fit into the narrative. In Russian journalistic jargon, the guidelines are referred to with the word “temnik”. In rare cases, written versions of these instructions emerge e.g. thanks to whistle blowers emerge from inside Russian media. These guidelines make life easier for editors who do not want to put the media they manage in danger: They know where the ever-changing red lines are.

But at the same time, this “smart” form of government control is itself just one part of a general campaign, whose final aim is not the media control and the shrinking space for free and independent journalism. The aim of the Kremlin’s media and communications strategy is to confuse and intimidate Russian and international audiences; to make us lose trust in fundamental democratic values, such as the importance of free media; and to spread a sentiment among domestic audiences that Russia is under attack by enemies who operate from the outside and from within.