By Michael Sheldon, for @DFRLab

On March 26, Facebook removed 2632 pages, groups, and accounts from its platforms, accusing them of inauthentic behavior. The largest subset of these, as outlined in a Facebook newsroom post, was a collection of 1907 pages, groups, and accounts linked to Russia.

The DFRLab had the opportunity to briefly look at some of these 1907 assets in advance. Facebook asserted in a blog post that the assets were removed “for engaging in spam — and a small portion of these engaged in coordinated inauthentic behavior — linked to Russia.”

Open-source analysis did not provide enough evidence to attribute the network to either Russian state or non-state actors. In addition, the range of topics in the assets were too broad to indicate any particular pattern across the pages. The evidence obtained, however, did provide an overview of the behavior patterns of the inauthentic Facebook pages and groups.

Many of the groups shared administrators and moderators and contained discernible clusters of related topics, such as the political situation in Ukraine. While the content was not exclusively political, the removal of content ahead of the first round of Ukraine’s presidential elections on March 31 was significant.

Low Engagement

The DFRLab first analyzed 87 pages among the 1907 assets. These pages generally covered a wide variety of topics, from technology sales, to news, to magic. It appeared as though the network had been engaged in a long-term operation, since some of the groups the pages managed dated back to 2012. The pages still appeared to have garnered negligible engagement overall.

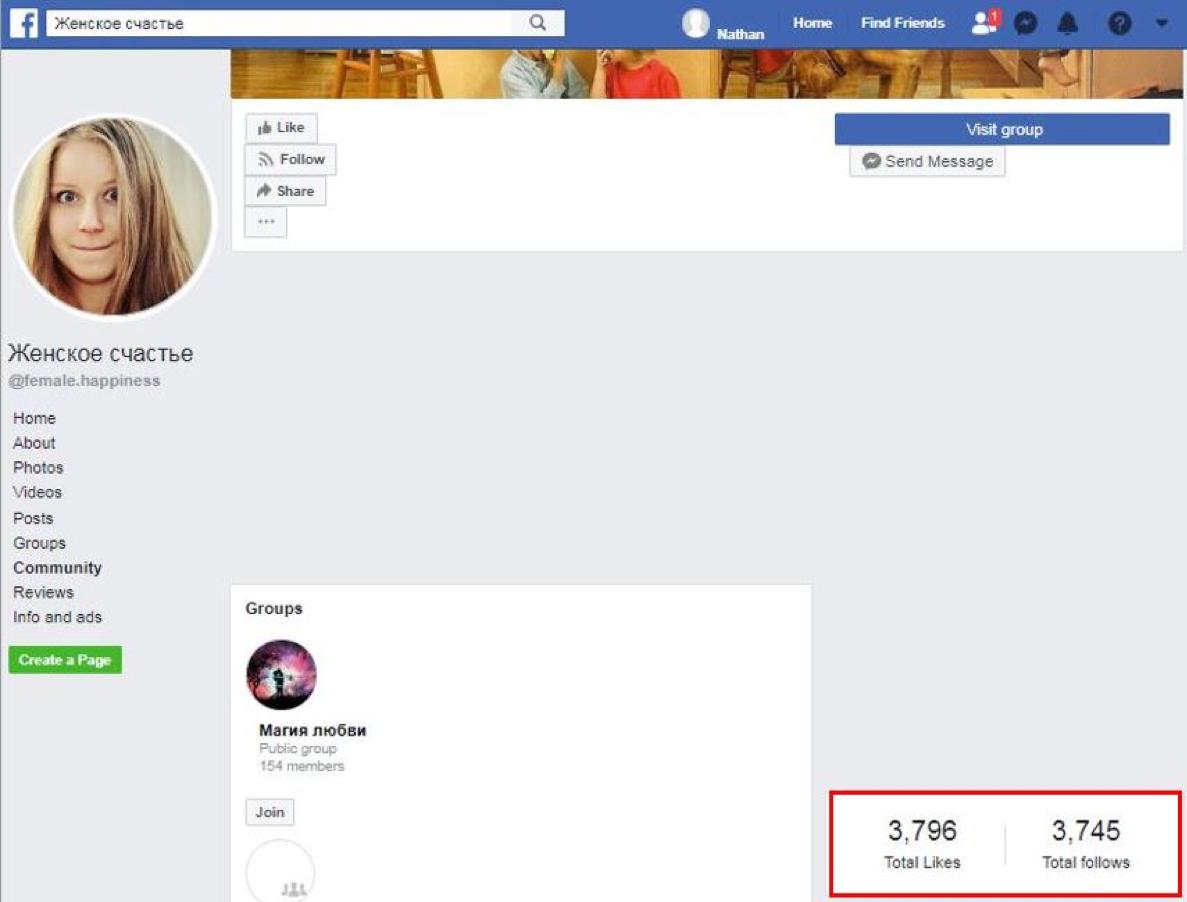

Of all the pages surveyed, a page titled Женское счастье (“Woman’s happiness”) had the largest following. This page garnered 3,796 likes and 3,745 follows within the five years after its creation in November 2014 — this like and follower count, while relatively modest by some standards, nonetheless made this page the most popular in the network.

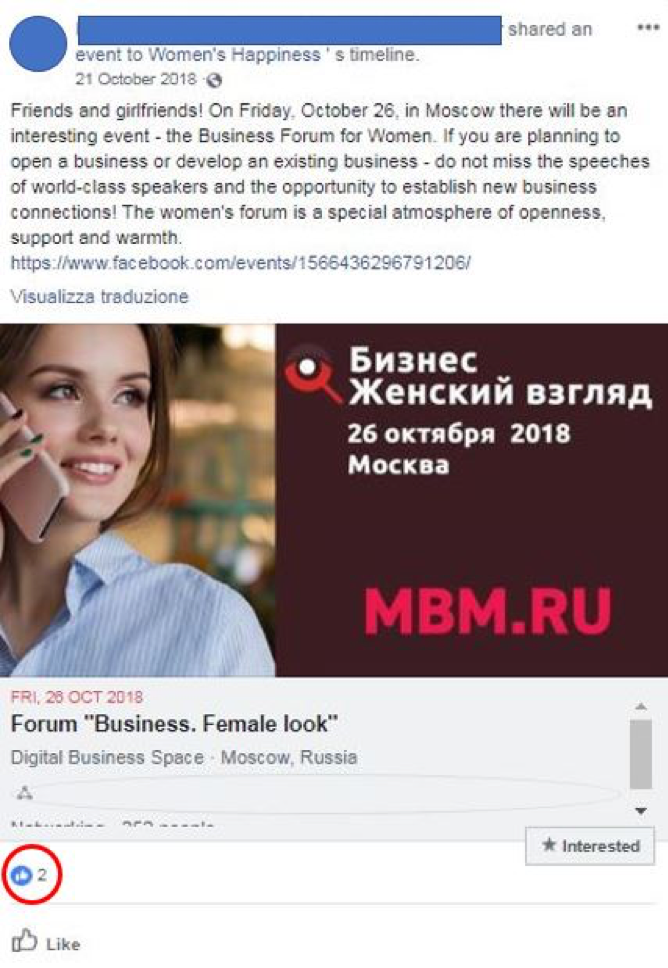

The individual posts by the Facebook page barely garnered any engagement.

The Patterns

One of the few pages that caught the attention of the DFRLab initially was a page called News. Despite having been created on October 20, 2016, the page had gained only 75 likes and 80 follows before its removal. The noteworthy feature of the page was not its number of likes — or even its content, for that matter — but rather, the communities it managed. This would come to be a defining trend across the pages surveyed in the network.

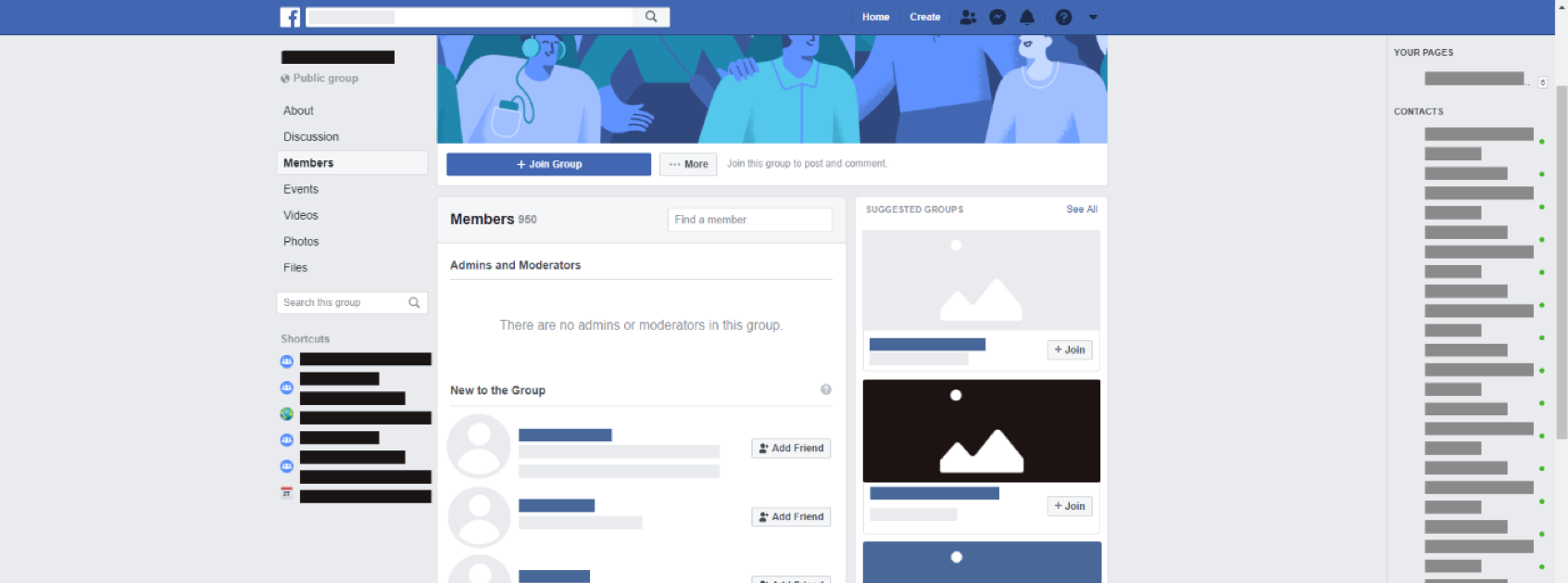

News was the administrator or moderator of 48 groups at the time of the takedown, several of which had over a thousand members. Among these, a number of Russian nationalist and post-Soviet political groups stood out. Although some of these groups were taken down, many remain standing, stripped of a moderation team. An anonymized snapshot below shows how the remaining groups will currently look. In contrast, groups that have been taken down will be completely inaccessible. The DFRLab was unable to determine why some groups were taken down and why some remained.

In addition to the administrator and moderation teams being stripped from these groups and having their accounts deleted, all content posted by these accounts to these groups also appeared to have been scrubbed. In the above graphic, for example, the standard banner image has replaced an aerial photograph as the banner following the takedown.

The Facebook page News exemplified how pages with otherwise little engagement bear their true value as managers of a wide array of groups. News, for example, managed a set of 48 groups that generally fit within the categories of Russian nationalist content, Bulgarian family content, Central Asian politics, general news in Russian, and local flea market groups. These groups were often co-managed by other pages and profiles that belonged to the network and that had also been taken down by Facebook.

Targeting Politics

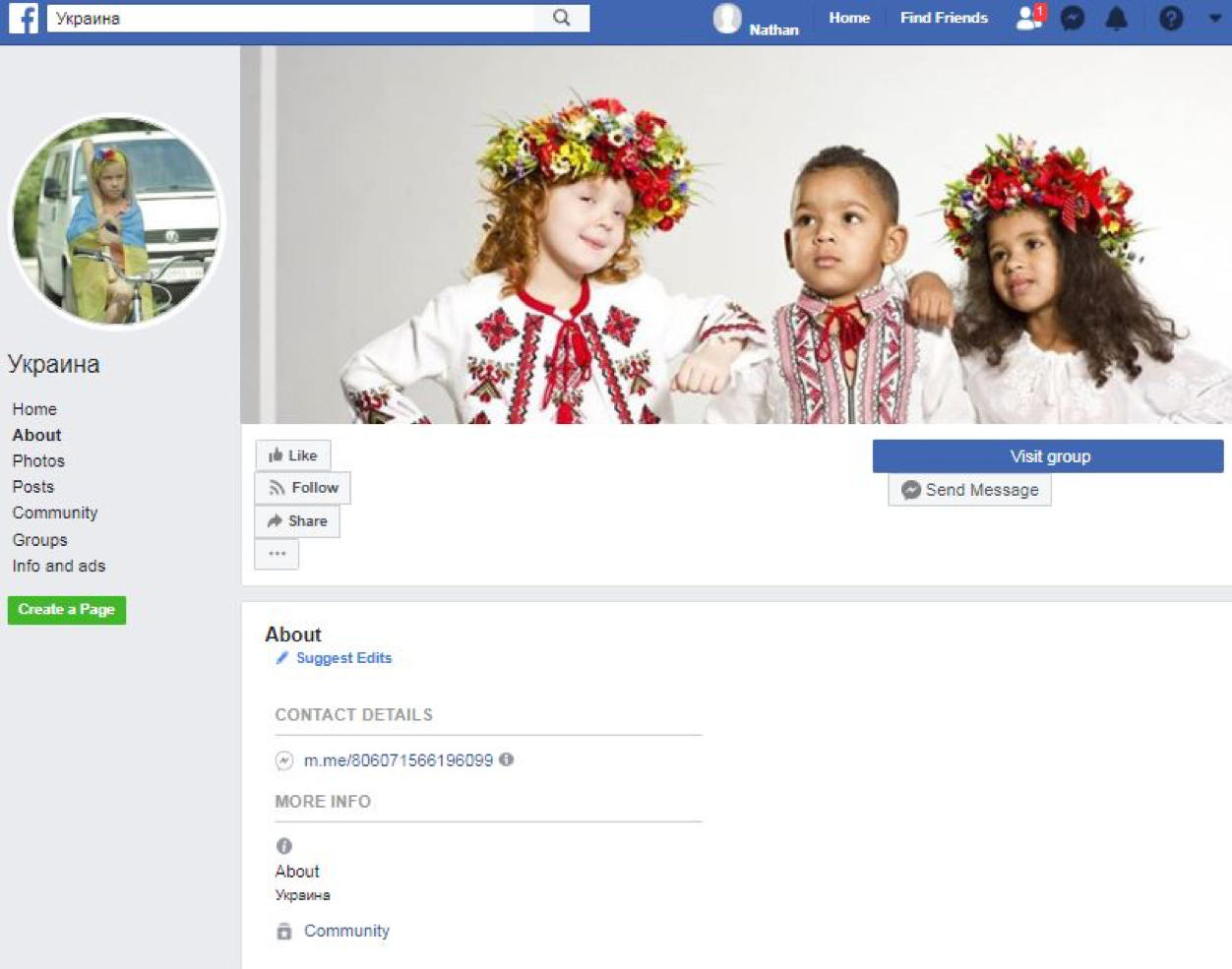

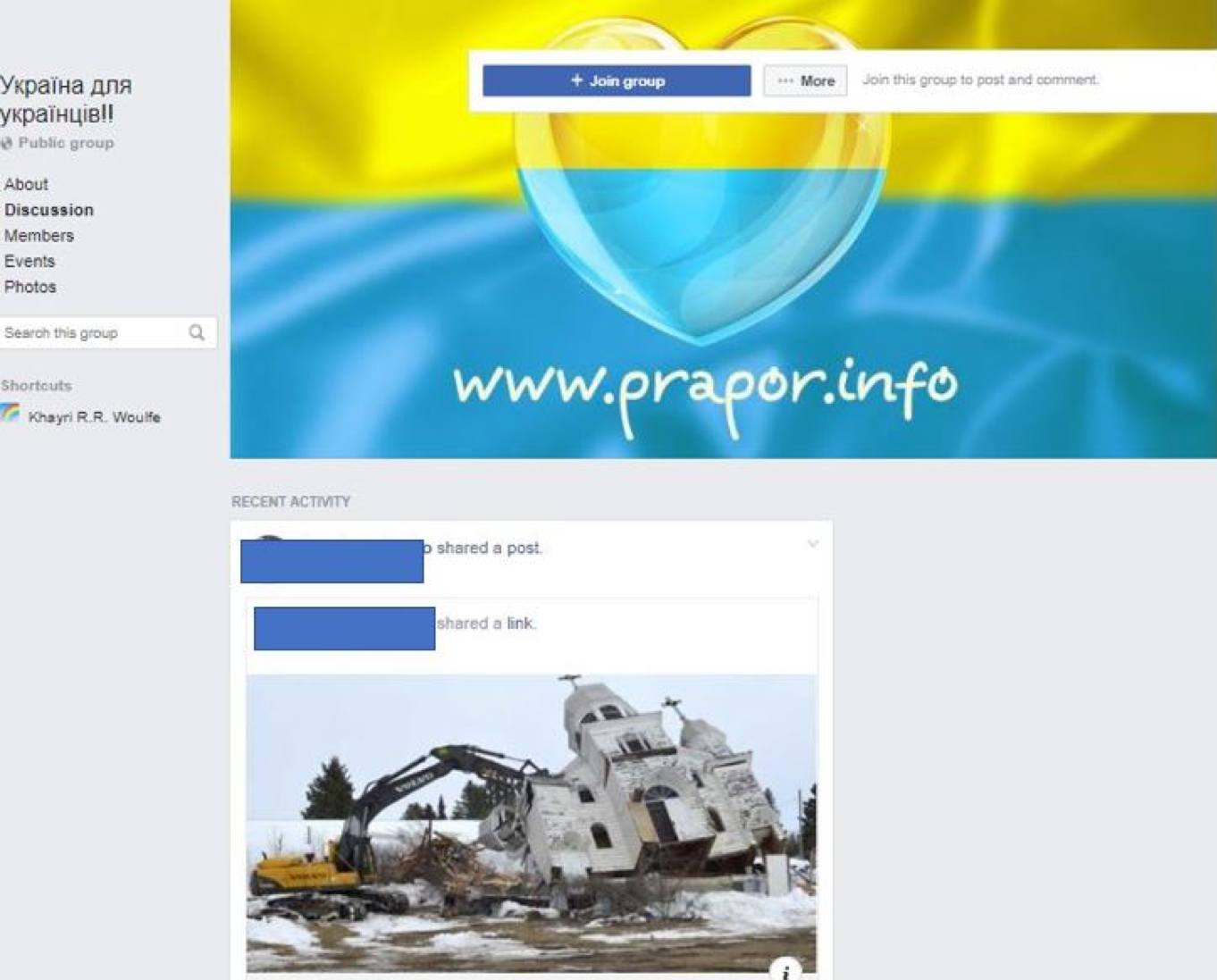

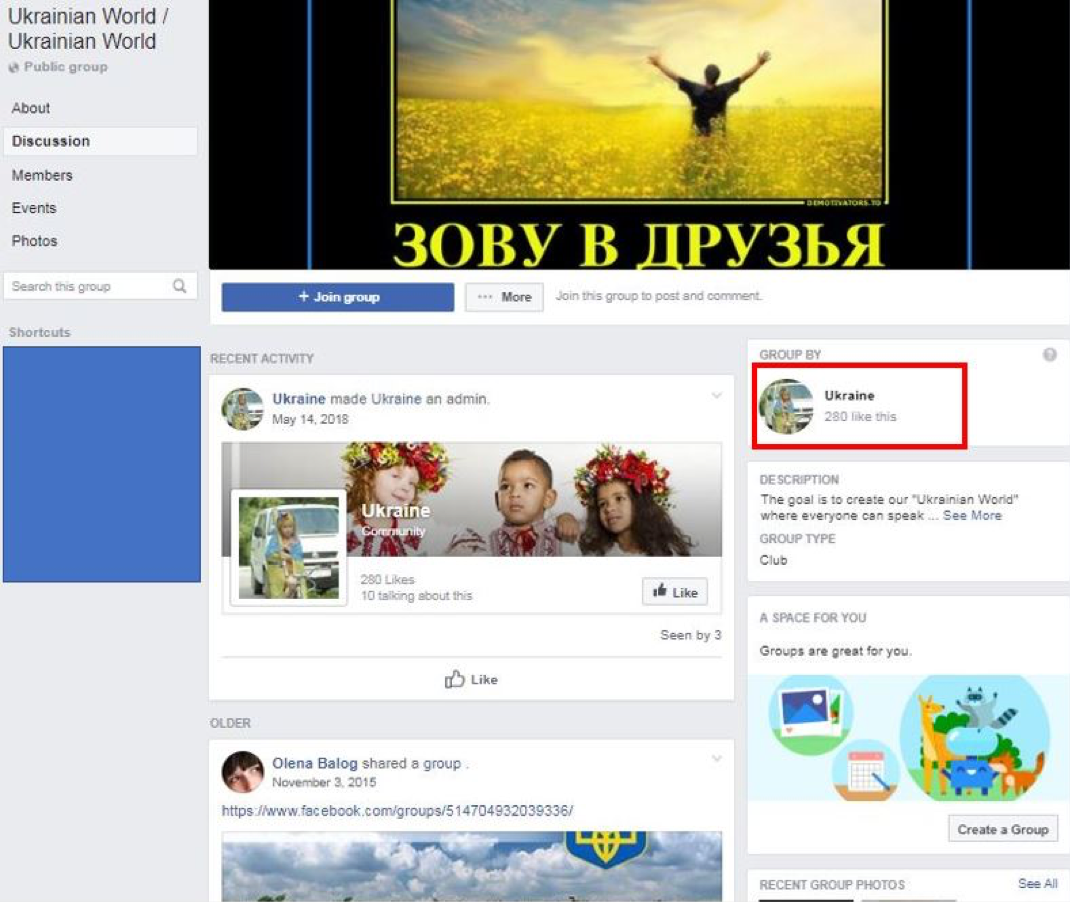

Another Facebook page active in the network was Украина (“Ukraine”), which managed several Ukrainian-themed groups. The page had garnered modest engagement–280 likes and 299 follows–since its creation in 2016, while barely gaining any engagement on Facebook posts. Similar to the Facebook page News however, this Facebook page managed several groups, some of which had significantly more members than Украина had likes or followers.

The Facebook groups managed by Украина (“Ukraine”) were mostly patriotic with regard to Ukraine, as suggested by their content and names, such as Украинский мир (“Ukrainian World”), Україна — це ти (“Ukraine is you”), Поддержи Армию Украины (“Support for the Ukrainian Army”), and Україна для українців!! (“Ukraine for Ukrainians”). It was noteworthy that many of the groups patriotic of Ukraine had names written in Russian.

The profile in the above graphic was a common administrator for many of the Facebook groups that were managed by the removed Facebook pages.

The Admins

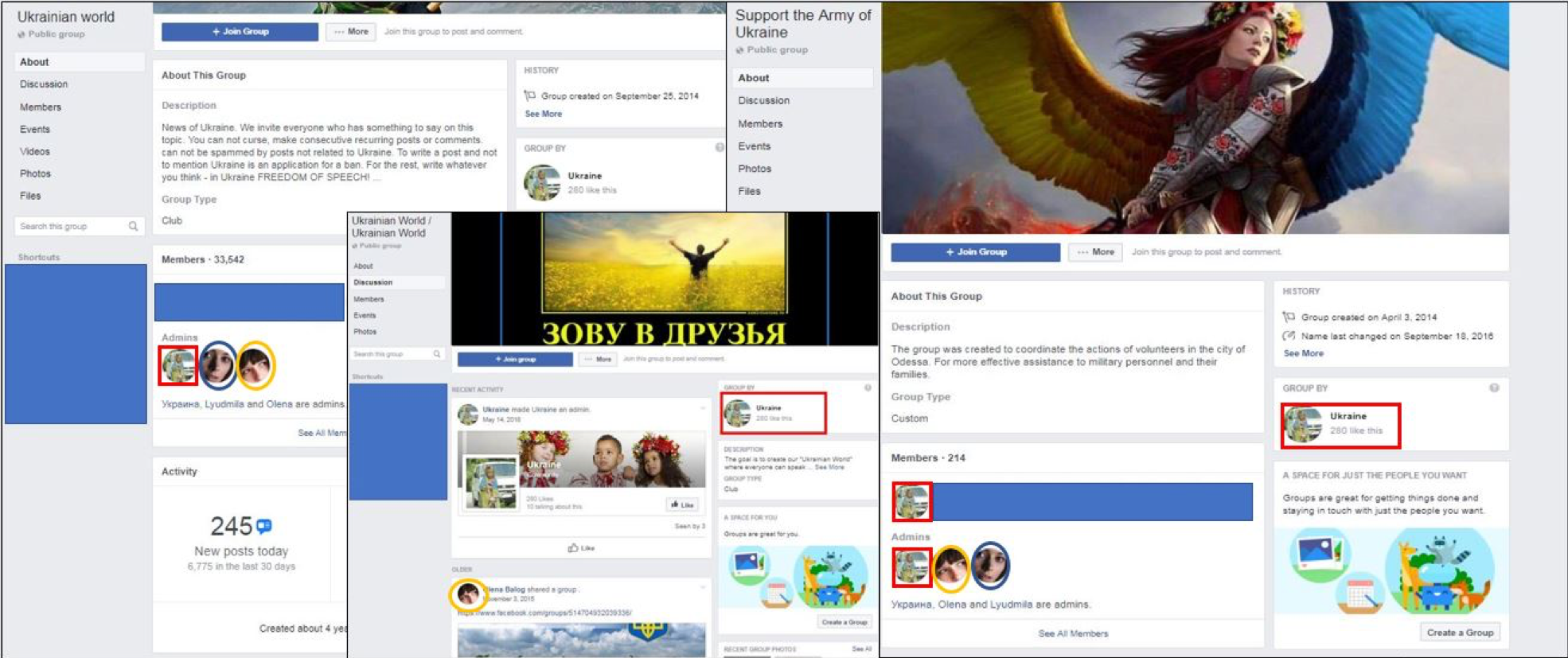

The Facebook groups provided insight into the connection between removed Facebook pages that seemed independent from one another at first glance, as well as into a small collection of individual accounts that served as common administrators and in charge of hundreds of groups.

The examples below demonstrated how a small collection of individual accounts, along with a larger collection of Facebook pages, managed several Facebook groups.

The removed Facebook page is highlighted above in red, while the two individual accounts managing many of the groups and participating in their discussions are highlighted in blue and orange, respectively. The DFRLab analyzed both individual accounts using inteltechniques.com, which is a tool that allows the user to input a particular Facebook account’s ID number to analyze that account’s social media activity.

There was a significant overlap of groups joined by both individual accounts. Some of these groups had names suggesting patriotic content in favor of Russia, such as РОССИЯ и МЫ ! Группа патриотов великой страны!!!(“RUSSIA and Us! A group of patriots of a great country !!!”) Both accounts thus appeared to have been members and, in some cases, even administrators of groups patriotic of Ukraine as well as groups patriotic of Russia. Furthermore, Google Reverse Image Search revealed that the profile picture of one of the individual accounts was a stolen picture from an actress, further supporting the suspicion of inauthentic behavior on the part of the account. The individual accounts were both removed.

In it for the Money

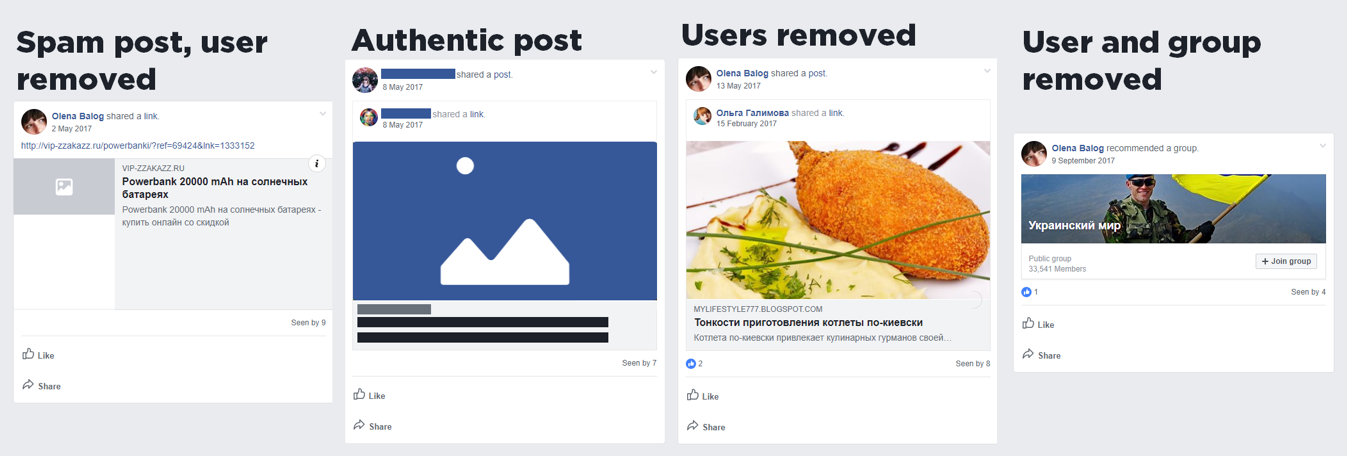

The graphic below shows posts from the removed group Український світ / Украинский мир (“Ukrainian world”), which was managed by the removed Facebook page Украина (“Ukraine”). It shows the different kinds of content one could expect to see on a group managed by the removed assets. The first post shows an example of a spam post — which were somewhat rare — which the group managers would post to the group, likely to collect advertisement revenue. These posts were generally spread out, allowing authentic posts to be the main feature of the group in order to grow the community.

With larger communities, more clicks will be driven towards links with advertisement revenue, even though they were somewhat scarce. A common feature of these groups was cross-promotion of similar groups managed by the removed assets. In the above graphic, the “recommended” group on the far right was part of the same network and taken down, but its Russian counterparts remains live as of writing this article.

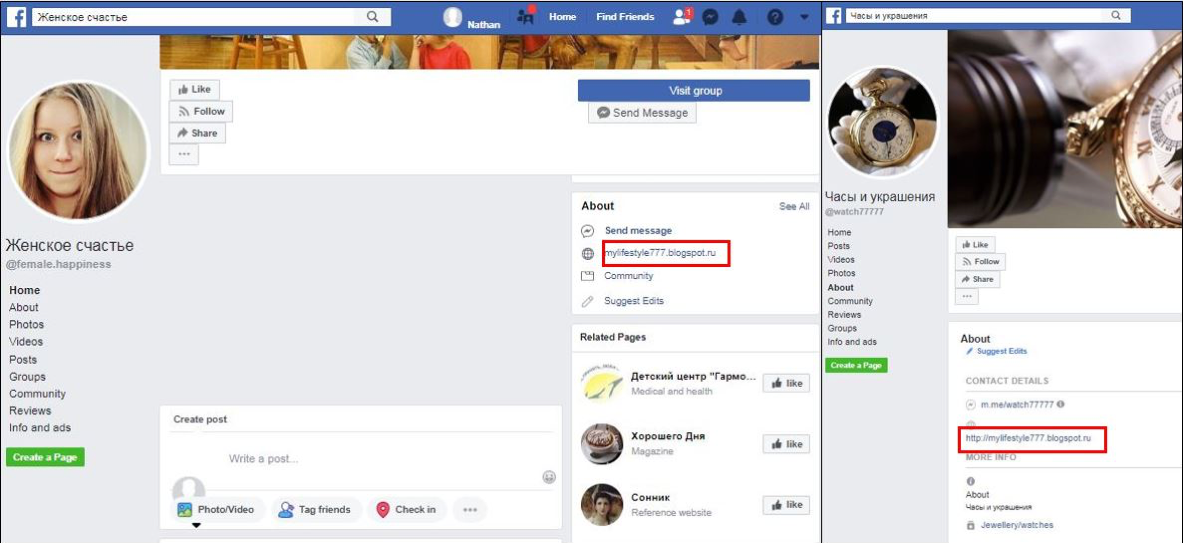

Two Facebook pages taken down by Facebook, Женское счастье (“Woman’s Happiness”) and Часы и украшения (“Watches and Jewelry”), appeared independent from one another at first glance. Both pages, however, were linked to the same commercial website — hosted on a Russian domain — that provided weight loss tips and outlined fashion trends. The common website suggests not only a possible commercial purpose behind the Facebook pages, but also hints at a more direct connection between them.

Conclusion

The assets in this takedown exhibited several common patterns and behaviors. First, they engaged in a creative and likely labor-intensive method of community building, in which a centralized set of accounts and pages were used for cross-promotion and subtle promotion of websites likely run by their owners. The DFRLab was unable to determine if the pages were run by multiple owners or a single person.

While the removed Facebook pages barely garnered any likes and followers, they often managed several groups with more members that featured active discussions. These groups seemed to be interconnected through a subset of administrators comprised of the removed, inauthentic individual accounts and Facebook pages.

Although broad in scope, the groups appeared to be organized in thematic clusters that had been identified as likely to drive high engagement from the communities they would attract over time. While many of the politically-sensitive topics discussed in the groups related to Russia and Ukraine, there was not enough open-source evidence to attribute the network to Russian state or non-state actors. Regardless, the ultimate aim of targeting sensitive topics such as Russian nationalism and the conflict-stricken Donbas region of Ukraine was likely not to inflame political tensions, but rather, to build communities that were active enough for the owners to drop monetized links inconspicuously.

By Michael Sheldon, for @DFRLab

This article was written by the Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensic Research Lab. You can find the original piece here.

Michael Sheldon is a Digital Forensic Research Associate at the Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensic Research Lab (@DFRLab).

Daniel Weimert is a Mercator Fellow currently assigned to the Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensic Research Lab (DFRLab).

Follow along for more in-depth analysis from our #DigitalSherlocks.