By Christine Schmidt, for NiemanLab

“French success resulted from a combination of structural factors, luck, as well as the effective anticipation and reaction of the Macron campaign staff, the government, and civil society, especially the mainstream media.”

If France could stop misinformation, could the U.S.?

A newly-translated-to-English report reflects on how the country handled misinformation and politically motivated document leaks in its 2017 presidential election and offers 50 recommendations for how gouvernements, société civile et acteurs privés could tackle similar problems. The findings are compiled in a hefty 200 pages from a working group between France’s foreign affairs minister’s policy planning staff and France’s research institute of the Ministry for the Armed Forces.

The group originally convened to explore developing an inter-agency task force dealing with information manipulation, their preferred term for fake news, defined as “the intentional and massive dissemination of false or biased news for hostile political purposes.” (Need a reminder for why it might be hazardous to our health to use that phrase? Here you go.) This report comes from the researchers’ approximately 100 interviews with national authorities, academics, and journalists in visits to 20 countries in Europe, Asia, and North America. Their guiding principle:

Information is increasingly seen as a common good, the protection of which falls into all citizens concerned with the quality of public debate. Above all, it is the duty of civil society to develop its own resilience. Governments can and should come to the aid of civil society. They should not be in the lead, but their role is nonetheless crucial, for they cannot afford to ignore a threat that undermines the foundations of democracy and national security.

(Yay for at least one government feeling that way.)

The report is chunky and full of deeper details on information manipulation and France’s response to early indications. Here are some of the highlights:

Why did #MacronGate not work?

On Friday, May 5, 2017 — two days before the second round of the French presidential election — someone(s) hacked 9 GB of data from the campaign of Emmanuel Macron, the eventual victor against right-wing leader Marine Le Pen.Two days before that, and two hours before the final televised debate between Le Pen and Macron, a user with a Latvian IP address posted fake documents on 4chan about Macron’s alleged offshore account — which were soon amplified by pro-Trump Twitter accounts using #MacronGate and #MacronCacheCash. BUT. There is good news.

“The leak did not significantly influence French voters, despite the efforts of the aforementioned actors. Why? French success resulted from a combination of structural factors, luck, as well as the effective anticipation and reaction of the Macron campaign staff, the government and civil society, especially the mainstream media,” the researchers concluded. Cultural clumsiness by the hackers and less reliance on ‘alternative’ websites helped, but so did the preparation and response of Macron’s campaign, existing government, and the mainstream media:

How France prepared

- Don’t do what the U.S. did: Paris had already observed the Democratic National Committee’s miserable response to its own hacking, plus American intelligence services had warned its French counterparts about Russian interference attempts during the French campaign.

- Rely on the proper administrative actors: France has two agencies in particular that were robust in watchdogging the campaigns, monitoring cybersecurity, and ensuring the integrity of the electoral results.

- Raising awareness via the media, political parties, and the public before and after the hacking: One of the aforementioned administrative actors even offered an open workshop on cybersecurity for the campaigns.

- Signal a united front: The government already in power showed its resolve and determination to stem foreign interference, both in its words and actions.

- Take technical precautions: The administrative actor heightened security at each step of the electoral process, even ending electronic voting for citizens abroad because of risk of cyberattacks.

- Pressure digital platforms to act: Facebook removed 70,000 suspicious accounts in France as recently as ten days before the vote took place, thanks to pressure from the government and from the public.

How France responded

- Highlight all hacking attempts: Macron’s campaign had already been talking about its susceptibility to hacking and responded in hours with a press release when the leaked documents were dropped.

- Beat the hackers at their own game: The campaign also placed traps along the way, using fake passwords, email addresses, and documents to throw them off, making the hackers explain why they stole and leaked information “which seemed, at best, useless and, at worst, false or misleading.”

- Hit back on social media: Campaign staff systematically and quickly responded to Macron Leaks posts or comments.

- Use humor: Dry, dull government-speak isn’t exactly as viral as being funny in responding.

- Call out actual propaganda outlets: Macron’s campaign ceased offering RT and Sputnik press credentials in late April and continuing in Macron’s presidency. Macron even highlighted their work as “organs of influence, of propaganda and of lying propaganda” during a joint press conference with Vladimir Putin, which must’ve been jolly.

- Compartmentalize communication as a rule of thumb: Use email only for trivial and logistic matters, use encrypted apps for confidential items, and save sensitive conversations for face-to-face.

- Call on the media to behave responsibly: “On Friday night, Macron’s team referred the case to the CNCCEP [one of the administrative actors] which issued a press release the following day, requesting ‘the media not to report on the content of this data, especially on their websites, [and] reminding the media that the dissemination of false information is a breach of law, above all criminal law.’ The majority of traditional media sources responded to this call by choosing not to report on the content of the leaks. Some have even gone one step further by denouncing an electoral interference attempt and calling upon their readers to not let themselves be manipulated.”

What’s the media’s role in this?

As mentioned above, the researchers make 50 recommendations for governing bodies, the general public, and private actors. Here are the top ones relevant to journalism:

- Don’t underestimate the threat: “The Finnish Security Strategy for Society insists that a good preparation against information manipulation depends on an accurate evaluation of the threat.”

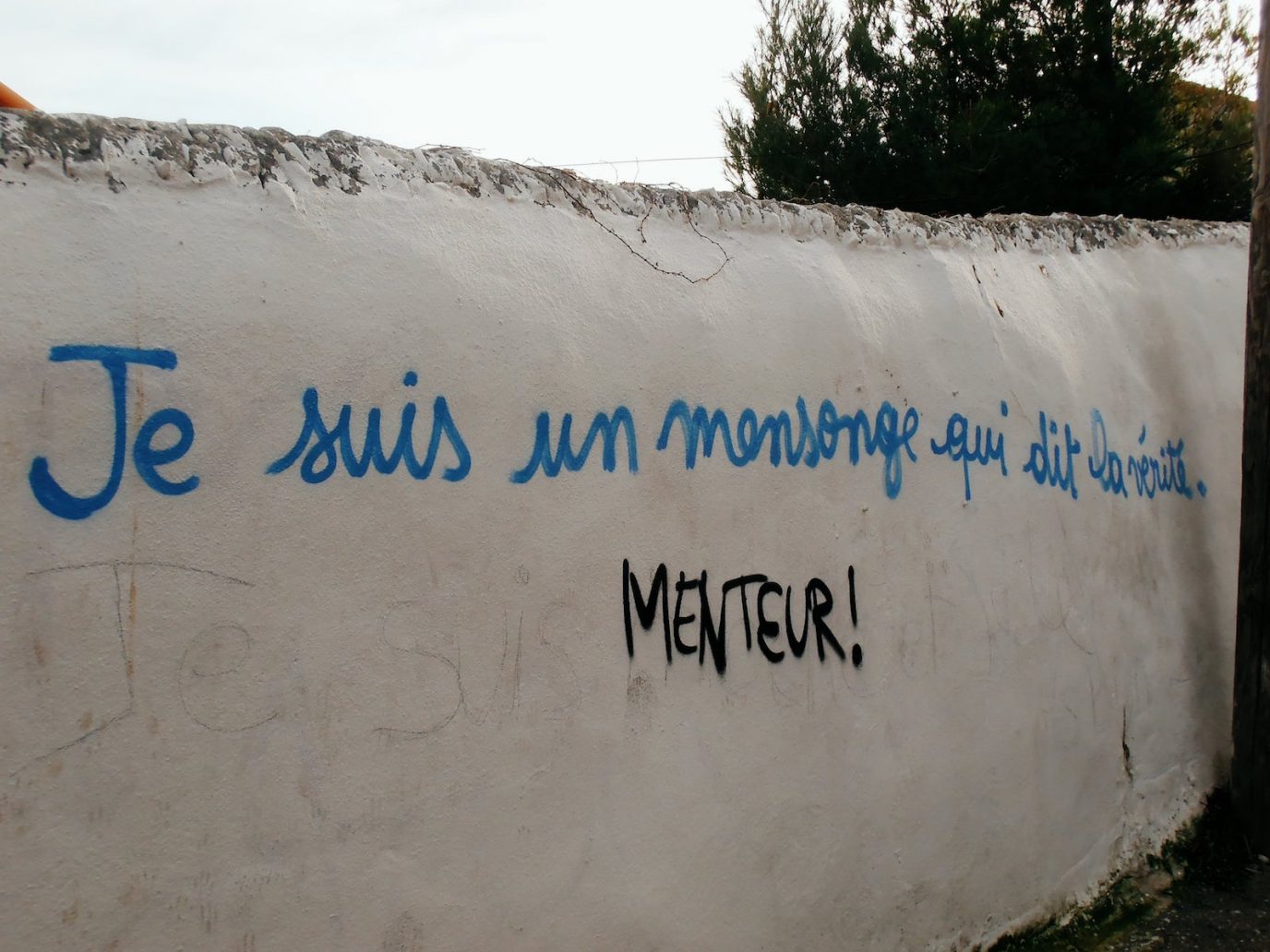

- Do not surrender the internet to extremists: “Conspiracy theories prosper all the more easily if they are not contradicted…It is necessary, however, to also give due consideration to the risk of the ‘boomerang effect,’ for to refute is also to reiterate. Every correction indirectly increases the circulation of the false information. This propagation effect cannot be avoided and it is therefore important to pick one’s battles, that is, to focus on counteracting those instances of information manipulation that are most dangerous.”

- Find a balance with government oversight: “Civil society (journalists, the media, online platforms, NGOs, etc.) must remain the first shield against information manipulation in liberal, democratic societies. The most important recommendation for governments is that they should make sure they retain as light a footprint as possible — not just in keeping with our values, but also out of a concern for effectiveness. As one of the roots of the problem is distrust of elites, any ‘top down’ approach is inherently limited. It is preferable to champion horizontal, collaborative approaches, relying on the participation of civil society.”

- Governments should hold digital platforms accountable, but also share information with them when helpful in a public-private cooperation: “Make the sources of their advertising public — by demanding the same level of transparency as is required of traditional media; implement adequate measures with which to fight information manipulation on their websites and contribute to the improvement of media literacy and the awareness of the general public of these issues.”

- Practice effective fact-checking: “Firstly, the correction must not directly undercut one’s vision of the world (otherwise it can even have the perverse effect of reinforcing the person’s primary beliefs — this was observed in the case of Iraq’s weapons of mass destruction, and discussions on climate change and vaccination). Secondly, the correction must entail an explanation of why and how disinformation was spread.”

- Adopt an international charter of journalistic ethics in a collaborative manner, involving both major traditional and online media. (Good luck on that one.)

- Train journalists on if one should and how to cover a massive leak, detecting a fake profile, reacting to extremist content. The researchers suggest using this as guidance.

- Build confidence in journalism by enhancing transparency, like The Trust Project’s model. (There are also many, MANY other initiatives trying to combat this problem.)

- Might as well round it out with this one: “Rethink the economic model behind journalism so as to reconcile the preservation of freedom of expression, free market competition and the fight against information manipulation.”

By Christine Schmidt, for NiemanLab