He never said Alaskans would live better under Moscow, but dozens of Russian news reports claim otherwise

Fake names and miserable wages: what it’s like to work in the Kremlin-friendly local Russian language newspaper.

Published in Latvia, Segodnya newspaper claims to be the only Russian-language daily in the European Union. I met one of the newspaper’s journalists Yelena Slyusareva three years ago on a trip to Sweden, sponsored by the Swedish embassy. As part of the trip the group of journalists went to interview the Swedish royal couple. Yelena’s English was poor, so interpreted for her from English to Russian. We got on alright.

While we were in Sweden, a controversial referendum on joining Russia was held in Crimea. Much like many issues involving Russia and Russians in the Baltic state of Latvia, the news coverage of this event in the Latvian-language press was vastly different from their local Russian-language counterparts. Latvians worried about the Russian aggression and did not hide their concerns that the Baltics may be the next in line Putin’s Russia may wish to “liberate”. For Segodnya, the annexation of Crimea was a happy reunification.

Yelena defended her newspaper: her colleagues really believed in what they wrote, she’d say. There was a plurality of opinions because her boss allowed her to pen an op-ed condemning Russia’s aggression in Ukraine. Yelena also criticized Latvia’s Russian population, who refused thinking with “their own heads,” surrendered “their power to the Russian television” and “closed their eyes as though they didn’t understand what was happening.”

Her op-ed was published, but half year later, in October 2014. Yelena says the article caused an uproar among her colleagues and readers: “Why did you have to offer your opinion when no one asked for it?”

About the same time as the article went to press, Yelena was on a Russian embassy sponsored trip to Crimea. She insists the embassy did not issue any guidelines on the coverage.

Journalist Yelena Shlusareva on a business trip to Crimea in 2014. Photo: Personal archive

From Crimea, Yelena brought back a series of articles. The first article stated that the trip had been paid for by the Russian embassy. The following articles didn’t.

Yelena said that the articles were not censored and she tried to show all sides of the complex story. One of them featured an interview with the editor of a newspaper in Yalta, who thanked Putin for the support. Another focused on the Crimean Tatars, who demanded the return of their homeland. However, she didn’t say anything when next to the article about the Tatars, an editor published an op-ed piece mocking their desire to become part of Europe, inviting them to visit Latvia to see how bad Europe really was.

A few months later, Yelena was laid off. The official reason was the staff downsizing, but “unofficially I have already been told: you need to understand that you cannot work in the Russian press with your viewpoints,” Yelena said. She asked to work at the newspaper for another month because she was preparing a residency permit for her mother and brother, who were fleeing to Riga from the war-torn eastern Ukraine.

“I was the only bread winner,” she says. She tried to argue with her editor, saying that the newspaper has been defending the residents of the eastern Ukraine, which was why it needed to help her, too. The editor responded, “It’s only business.” He allowed her to work until the end of the month.

Sergey Storchevoy, who worked as a publishing company manager at that time, questioned her side of the story to Re:Baltica. He said Yelena’s dismissal had nothing to do with her political views, but with the staff cuts and an opportunity to hire better journalists to replace her.

I contacted Yelena again as part of the investigation into owners of internet sites that cover events in the Baltics in a same vein as the Kremlin-controlled news media.

Journalists run to Moscow

“Putin’s women will break noses of the NATO soldiers,” screamed a headline on website vesti.lv, sister-publication to the newspaper Segondya, on Feb 21, 2017.

Under the click-bait headline was a recycled article by the Russian state-run news agency RIA Novosti, which quoted The Times (UK) report on possible use of local women to stage provocations against the NATO soldiers. The original headline of article in RIA Novosti is softer: “People in Estonia fear that Moscow will provoke NATO troops for a brawl.” The article was also reprinted by the Sputnik web site, which together with RIA Novosti makes up part of the state-run media conglomerate Rossiya Segondya.

It is a standard practice for vesti.lv to republish articles produced in Russia, slapping on more provocative headlines.

In another example rubaltic.ru, a Kaliningrad-based news site, writes that The Baltic States will close the door to guest workers. Vesti.lv re-publishes the same text under the headline Latvia is dying out. There’s no one left to work.

The article about Putin’s women was signed by Anatoly Tarasov. It was a busy day for him. It started at 6:50 a.m. with the news item about the EU preparing “a new russophobic plan”, moving on to story about a new music video by an American singer Lana del Rey. Then he filed a piece informing the audience how Latvia’s non-citizens — mostly Russian-speakers — can obtain citizenship of a Moscow-backed, internationally unrecognized Donetsk People’s Republic in eastern Ukraine. It was followed by an article about refugees fleeing Lithuania. The day concluded with a review of a Hollywood movie at 4:29 p.m. On that day, Tarasov wrote more than 20 articles.

You won’t find this prolific journalist on social networks or in local journalist organizations. Anatoly is a work of fiction. Journalists at vesti.lv can select one of several aliases, so to create an illusion of a team work, even though it is only one person who copies and pastes news articles from various news sources on the internet, according to several former vesti.lv journalists who requested anonymity to Re:Baltica.

Andrey Shvedov, the newspaper’s editor-in-chief, couldn’t find the time to give us an interview. That’s why I started talking to his journalists.

At least two of them have moved permanently to Russia.

One is Vladimir Veretennikov, who often writes for the Russian news site lenta.ru.

Lenta.ru used to be a very popular and influential Russian news website. After the editor-in-chief was fired over the coverage of the conflict in Ukraine back in 2014, part of their old team quit in protest and moved from Moscow to Riga to build up their new news project called meduza.io.

Attempts to contact Veretennikov were unsuccessful. However, a contact with another recent Moscow transplant of Segodnya, Dmitry Mart, turned into a lengthy email exchange. He said he was tired of “reading every day about the integration and the state language inspection. When the fascist Germany existed, many moved away to live somewhere else. In Moscow, I live in harmony and free.” The salary of the Russian-language journalist in Latvia, which is almost never publicly discussed in Latvia, is smaller than the salaries of their Latvian-speaking colleagues. The journalists interviewed by Re:Baltica say they would get between 300 to 500 euros a month after taxes. Mart says life in Moscow doesn’t have to be that expensive. An apartment and potatoes are even cheaper than in Riga, he wrote.

Another Segodnya journalist, Andrey Tatarchuk, agreed to meet in person. The vigorous, smiling man of about 50 years old, Tatarchuk said that Segodnya publishes negative articles about Latvia because its audience demands it. A similar argument was put forward by other former journalists, however none of them was able to say who its target audience was. The common line was that it’s pensioners or disillusioned men of the pre-pension age, whose media diet includes Russia’s TV channels which have been available through cable TV providers in Baltics.

“At some point, the local Russian-language media got this impression that the Russian readers have this point of view,” said Slyusareva. “Readers, whenever I meet them, no longer necessary hold to these views. Yet the newspaper continues to peddle them and, as a result, continues to lose readership.”

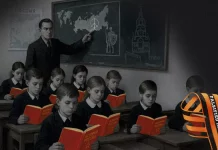

Illustration: Lote Lārmane

Who owns Segodnya?

Segodnya newspaper is not profitable. According to the Latvia’s business registry, the official ownership of the newspaper has changed three times since 2012. What is suspicious is that while the company names have changed, the people who owned those companies remained the same. It likely is done to avoid paying back taxes, which as of February 2017, were more than 300,000 euros.

Illustration: Lote Lārmane

The last ownership swap took place in the summer 2016 when a 23-year-old graduate of the Ukraine State Aviation University, Ivan Khreskin, became the new owner. He got not only the newspaper, but more than 200,000 euros debt in unpaid taxes. When Re:Baltica’s colleagues tracked him down in Ukraine, Khreskin admitted that he knew that he was the owner of some media outlet in Latvia, but that was all.

It’s much harder to collect tax debt from foreigners. It’s probably why one of the previous owners of the publishers was a Belarusian citizen who ended up with a bill of 100 000 EUR.

As of right now, the newspaper Segodnya is published by Media Nams Vesti, on paper owned by a 46-year-old Ludmila Kalashnik. It’s an open secret among the Russian-language journalists in Latvia that a true owner is her partner, former member of the Russian Duma and a millionaire Eduard Yanakov.

It was first reported in 2012, when two local Russian-language newspapers, Chas and Vesti Segodnya, merged. Later, the more liberal-leaning daily newspaper Telegraf was added to them. The owners hid behind offshores, however, the media mentioned the names of the Russian billionaire Andrey Molchanov, Yanakov and Latvian businessman Artur Yeresko.

A newspaper, a business, a football club

Eduard Yanakov, former member of the Russian parliament, integrated in Latvia. Art by Mārtiņš Upītis.

Yanakov in Latvia has an oligarch’s mini-set: a business, a newspaper and until recently a football club.

To obtain the “golden visa” or EU residency permit issued by Latvia, he purchased a 400-square-meter flat in a prestigious art nouveau district in Riga for almost 1.5 million euros. His partner Kalashnik bought a house for almost 1.5 million euros in a prestigious area in the nearby seaside resource Jurmala, popular among the wealthy in the former Soviet Union.

People who worked in management positions at the time of the newspaper mergers say that Yanakov considered the newspapers as a business. With time, he became the sole owner and attempted to pour some life into his failing media empire, but failed. Some workers were not paid on time. Others have been laid off. It turned out running a newspaper was not the same as mining coal.

Wearing a T-shirt, Yanakov regularly showed up in his office, located near the newsroom. He didn’t get involved with the newspaper’s content, but it was not necessary. “Segodnya totally reflected the official position of the Russian embassy here — intentionally or not, but that’s a fact,” says Slyusareva.

For example, shortly before the European parliament elections in May 2014 the newspaper suddenly started to publish a lengthy op-eds by one of the candidates, openly pro-Kremlin MEP Tatjana Zdanoka, in which she criticised the Latvian government and EU policies.

A representative of the Member of the European Parliament from Latvia Tatjana Zdanoka says that they did not pay to publish long op-ed pieces by Zdanoka ahead of the elections to the European parliament. The press releases were so interesting that Segodnya decided to publish them for free.

None of the articles mentioned that it was paid content. Zdanoka denies it. In her words, the newspaper republished her press releases as they were seen important. Tatarchuk, when asked about whether the timing of these articles with the upcoming elections was a coincidence, heartily laughed. “Perhaps,” he said.

Conversation with Yanakov himself was short. “I don’t speak with the media. Ask the newspaper management,” he said.

Nowadays Yanakov is rarely seen in newspaper offices. The last time was at a New Year’s party. He brought the red caviar.

But there is someone who sees him almost every two weeks: Alexander Pronin, manager of the Riga Football Club. In February, I met with him in a stadium cafeteria as the club is in training. The team had just returned from the boot-camp in Dubai, paid for by Yanakov and other sponsors. Pronin is a man of the athletic build, taciturn. He wants to know the goal of the article.

Pronin says that he and Yanakov founded the football club two years ago because they wanted to raise the prestige of the sport. They have also been looking for a place in Riga to build a stadium.

According to Pronin, the club’s last year budget was around 550,000 euros, largely coming from Yanakov. Smaller donors will be seen at the annual report at the end of the year. The long-term goal is to make money by competing in the UEFA championships.

There was no indication that few weeks later Yanakov will disappear from the list of club’s owners, as the listings from Latvian business register show.

A new package, an old product

Meanwhile, Slyusareva now writes for a Russian-language news site press.lv. Among the Russian-speakers, the site previously used to be known as ves.lv: web outlet for Vesti Segodnya newspaper. The domain press.lv has been registered by the son of a Riga city council member Andrey Kozlov from the Harmony party (a political force in Latvia often accused of sympathising with the Kremlin), also named Andrey Kozlov. Harmony party draws its support mostly from the Russian speakers. Kozlov is also one of the original owners of the newspaper Segodnya, but he left that business.

Slyusareva says that the news site is producing real journalism. As an example, she mentions an article uncovering a piece of fake news published by her former employer as though the Latvian state will start confiscating illegal satellite dishes to prevent people from watching Russian TV. The article’s author is a former member of Latvian parliament Nikolai Kabanov.

If it hadn’t been for press.lv, Slyusareva would have left journalism. “There are too few Russian publications. Those that exist are small and similar to one another. It’s hard to uphold your principles because you cannot make enough money for yourself,” she says. She manages to earn about 400 euros a month and says it’s no wonder that Russians who grew up in independent Latvia do not absorb the local Russian press or want to work there. Instead, the Russian-speakers would rather switch on the bling on Russian TV.

*Correction, 30.03.2017. The original article has been updated to correct the inaccurate statement that the domain press.lv was registered by a member of the Riga city council Andrey Kozlov – the domain has been actually registered by his son, also named Andrey Kozlov.

By Inga Spriņģe, Re:Baltica