By Donald N. Jensen, for CEPA

President Donald Trump met briefly on 20 June with Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko, who used his first White House visit under the Trump administration to stress his country’s alliance with Washington. A White House statement said the two leaders discussed “support for the peaceful resolution to the conflict in eastern Ukraine and President Poroshenko’s reform agenda and anti-corruption efforts.” Poroshenko held separate meetings with Vice President Mike Pence and other U.S. officials.

Poroshenko’s visit came as both the United States and Russia have signaled interest in improving relations. Those ties have long been strained not only by Western sanctions imposed against Moscow for annexing Crimea and invading eastern Ukraine, but also by Russia’s provocative behavior in Central and Eastern Europe, its involvement in Syria’s civil war and its interference in the 2016 U.S. presidential campaign. Nevertheless, the fact that Trump met Poroshenko before Russian President Vladimir Putin and the U.S. Treasury’s announcement the day before of new sanctions on dozens of Russian individuals and companies somewhat dispelled widespread concerns that Trump would undercut Kyiv in favor of rapprochement with Moscow.

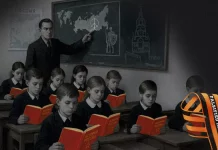

Moscow was clearly not pleased, but the Kremlin’s media strategy covering the Poroshenko visit reflected quite different objectives. On one hand, coverage by state-controlled RT and Sputnik—which primarily target foreign audiences—was relatively low-key. This reflects the Kremlin’s desire to be seen abroad as a constructive player in resolving the Russia-Ukraine impasse, even though it remains a fierce critic of Ukraine’s leadership and has shown little sign of living up to its Minsk framework obligations. In one article, Sputnik seemed to push the idea that Poroshenko was trying to get Trump to invest in Ukraine or get “materially invested in the war in Donbass,” and that U.S. firms would receive 90 percent of the rebuilt infrastructure under such a deal. A second article stressed that while the meeting was a “political success” for Poroshenko, overall it was unlikely to bring any “tangible” benefits to Ukraine. (Sputnik was also highly critical of the new sanctions and gave prominent play to threatened impeachment proceedings against Poroshenko in the Ukrainian parliament).

On the other hand, at home, Russian TV coverage appeared aimed at reigniting the heated, anti-Ukrainian popular mood that had rallied many Russians behind the 2014 military invasion. On one riotous audience participation program, Time Will Show—often packed with anti-American material, and with prominent journalists and Duma members as participants—the message was that Poroshenko’s trip to Washington showed that America’s “Ukraine project” is collapsing. The show compared Poroshenko’s press conference by the White House fence to the homeless people who often gather nearby. Another participant said Trump’s treatment of Poroshenko reminded him of a child invited to a Kremlin New Year Party. The only thing lacking, he said, “were the candy wrappers around Poroshenko on the floor.” Other programs noted Trump’s use of the expression “the Ukraine” rather than simply “Ukraine.” Some Ukrainians find that terminology insulting because it appears to undermine their status as an independent nation.

Patriotic mobilization has been the Kremlin’s way of shoring up public support; if Russia was being pressured by external enemies, then those enemies could be blamed for the economic crisis and other domestic problems. Russians overwhelmingly supported the Crimea annexation, and the general consensus among political observers was that national pride had boosted support for the Kremlin. Indeed, a Levada poll released in April 2017 suggested that as the economic crisis dragged on, it was the perception of the re-establishment of Russia’s status as a great power that formed the basis for Putin’s still very high poll ratings. Reforming and improving military readiness and strengthening Russia’s international standing had replaced higher living standards and economic development as among Putin’s top “successes.”

But the “Crimea effect” seems to be declining, no matter what the Kremlin puts on TV or how reluctant most Russians are to let Ukraine go. Although Putin’s approval rating remains high, a recent poll by the Pew Research Center found that support for Putin’s “strongman” handling of foreign policy appears to be shrinking. The public is just as concerned about the poor state of relations with Brussels and Washington, and is beginning to tire of Russian intervention in Ukraine.

At the moment, the Kremlin must find a way to create another “patriotic wave” or otherwise rally the population, while defusing growing public dissatisfaction with the economy, official corruption and abuse of authority. The recent truckers’ strike, protests by farmers in Krasnodar and Muscovites’ protests against a municipal plan to demolish as many as 8,000 five-story residential buildings represent the kind of genuine mobilization the authorities find threatening and may be unable to channel even if they do not necessarily indicate that the Kremlin is in any immediate danger.

By Donald N. Jensen, for CEPA

Donald N. Jensen is a Senior Adjunct Fellow at the Center for European Policy Analysis where he edits the StratCom weekly Editor’s Note. Jensen is also a Senior Fellow at the Center for Transatlantic Relations, Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies. A former U.S. diplomat, he writes extensively on Russian foreign and domestic politics, especially Russia’s relations with Europe