By Laura Hazard Owen, for NiemanLab

Plus: “There is no bygone era of a well-informed, attentive public. What we have had in lieu of a well-informed citizenry is what might be termed a ‘load-bearing’ myth — the myth of the attentive public.”

The growing stream of reporting on and data about fake news, misinformation, partisan content, and news literacy is hard to keep up with. This weekly roundup offers the highlights of what you might have missed.

“People can self-generate their own misinformation. It doesn’t all come from external sources.” Researchers at Ohio State found that even when people are provided with accurate numerical information, they tend to misremember those numbers to match whatever beliefs they already hold: “For example, when people are shown that the number of Mexican immigrants in the United States declined recently — which is true but goes against many people’s beliefs — they tend to remember the opposite,” OSU’s Jeff Grabmeier reports in an article summarizing the research on Phys.org (the full paper is here).

110 people were presented with “short written descriptions of four societal issues that involved numerical information.” On two of the issues, the statistics fit the conventional wisdom; for two of the issues, the statistics belied it.

For example, most people believe that the number of Mexican immigrants in the United States grew between 2007 and 2014. But in fact, the number declined from 12.8 million in 2007 to 11.7 million in 2014.

After reading all the descriptions of the issues, the participants got a surprise. They were asked to write down the numbers that that were in the descriptions of the four issues. They were not told in advance they would have to memorize the numbers.

The researchers found that people usually got the numerical relationship right on the issues for which the stats were consistent with how many people viewed the world. For example, participants typically wrote down a larger number for the percentage of people who supported same-sex marriage than for those who opposed it — which is the true relationship.

But when it came to the issues where the numbers went against many people’s beliefs — such as whether the number of Mexican immigrants had gone up or down — participants were much more likely to remember the numbers in a way that agreed with their probable biases rather than the truth.

In a second study, participants played a “Telephone”-like game. The first person in the chain saw the correct “saw the accurate statistics about the trend in Mexican immigrants living in the United States (that it went down from 12.8 million to 11.7 million),” wrote those numbers down from memory and passed them on to a second person, who did the same with a third person, and so on.

Results showed that, on average, the first person flipped the numbers, saying that the number of Mexican immigrants increased by 900,000 from 2007 to 2014 instead of the truth, which was that it decreased by about 1.1 million.

By the end of the chain, the average participant had said the number of Mexican immigrants had increased in those 7 years by about 4.6 million.

“These memory errors tended to get bigger and bigger as they were transmitted between people,” [study coauthor Matt Sweitzer] said.

At least 30 journalists worldwide are imprisoned for spreading “fake news.” That’s a huge increase since 2012. At least 250 journalists are in jail worldwide for reasons related to their work, the Committee to Protect Journalists said this week in its annual report. Of those, “the number charged with ‘false news’ rose to 30 compared with 28 last year. Use of the charge, which the government of Egyptian president Abdel Fattah el-Sisi applies most prolifically, has climbed steeply since 2012, when CPJ found only one journalist worldwide facing the allegation.”

It wasn’t this way five years ago, said Courtney Radsch, advocacy director of the CPJ, which tracks these trends.

In 2012, there was just one journalist in jail on fake-news charges. By 2014, there were eight. Then came 2016, when the most dramatic rise began, in which 16 journalists worldwide were in jail on fake-news charges. The number rose to 27 in jail by the end of last year.

Overall, between 2012 and 2019, there have been 65 journalists imprisoned on false-news charges. For comparison, since 1992, when the CPJ started tracking the trend, an overall 120 journalists have at one point been locked up for spreading so-called fake news. That means more than half of the journalists jailed on these charges were in prison sometime in the past seven years.

Most of the journalists who have been jailed on fake news charges over the past 7 years are in Egypt (7), followed by Turkey (6), Somalia (5), and Cameroon (5). Singapore passed a restrictive fake news law this year.

“Strategic intent is not strategic impact.” Digital disinformation campaigns can be large and organized — and still have very little impact on their targets, writes David Karpf, an associate professor of media and public affairs at George Washington University, in MediaWell. (MediaWell is run out of the Social Science Research Council, the independent nonprofit that, among other things, is assisting on the project that gets Facebook to share data with academics. It’s not going that well, reportedly!)

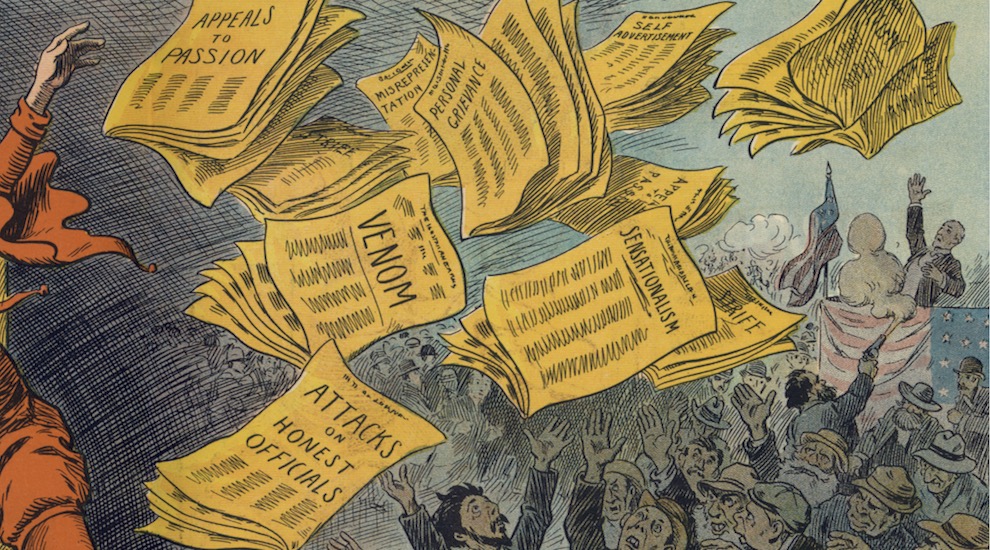

Much of the attention paid by researchers, journalists, and elected officials to online disinformation and propaganda has assumed that these disinformation campaigns are both large in scale and directly effective. This is a bad assumption, and it is an unnecessary assumption. We need not believe digital propaganda can “hack” the minds of a fickle electorate to conclude that digital propaganda is a substantial threat to the stability of American democracy. And in promoting the narrative of IRA’s direct effectiveness, we run the risk of further exacerbating this threat. The danger of online disinformation isn’t how it changes public knowledge; it’s what it does to our democratic norms. […]

The first-order effects of digital disinformation and propaganda, at least in the context of elections, are debatable at best. But disinformation does not have to sway many votes to be toxic to democracy.

By Laura Hazard Owen, for NiemanLab