By Ben Nimmo, for DFRLab

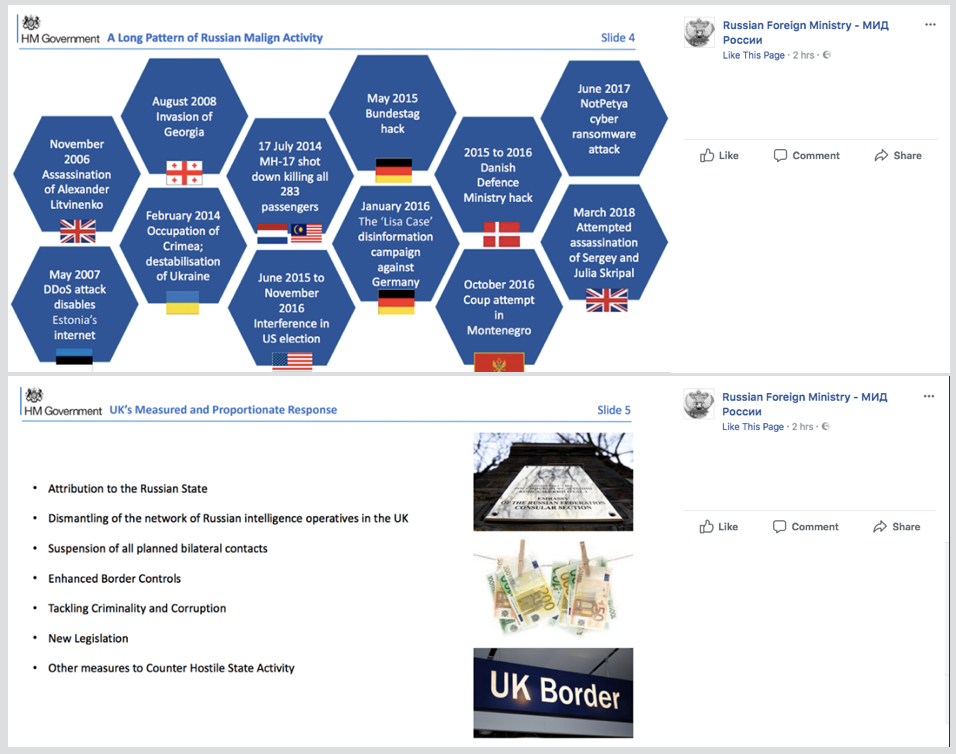

On March 27, the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA) posted a scoop on Facebook and Twitter: independent daily Kommersant acquired a set of “notorious classified files” from the United Kingdom, which allied and partnered governments allegedly used to justify their mass expulsions of Russian diplomats in response to the poisoning of ex-spy Sergei Skripal on British soil.

The “notorious classified files” consisted of six slides, which, despite the peril of declassifying allegedly secret material, we reproduce below.

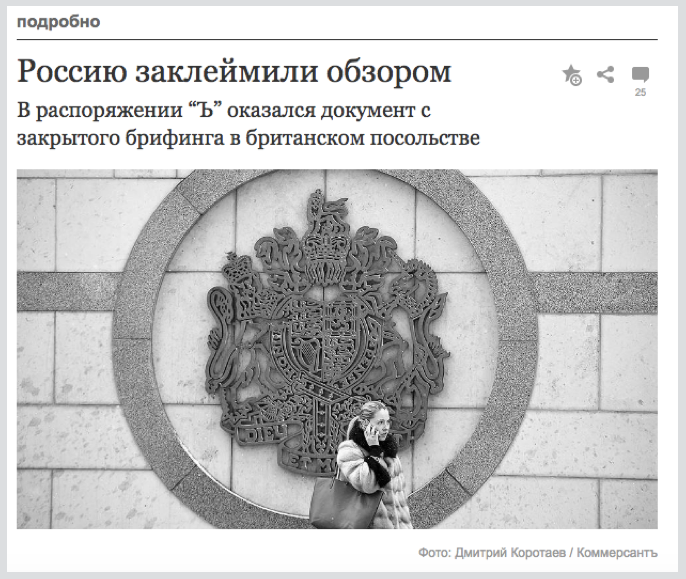

The MFA sourced its post to a Kommersant article (archived here), which did, indeed, present the six slides as a “document from a closed briefing in the British Embassy” in Moscow (PDF of slides here). Kommersant described the briefing as being given to “representatives of foreign embassies” in Moscow.

The MFA shared the Kommersant slides and a link to the article, with a subtle change in language: rather than describing the briefing in general as “closed” (in Russian, “закрыт”), it described the files in particular as “notorious” and “classified” (in Russian, “секретные,” secret, without the word “notorious”).

“Only 6 pictures were needed to take decision on one country’s responsibility for a gas attack. You can evaluate by yourself, whether those files are enough — the pictures are attached,” the MFA wrote on its Facebook page.

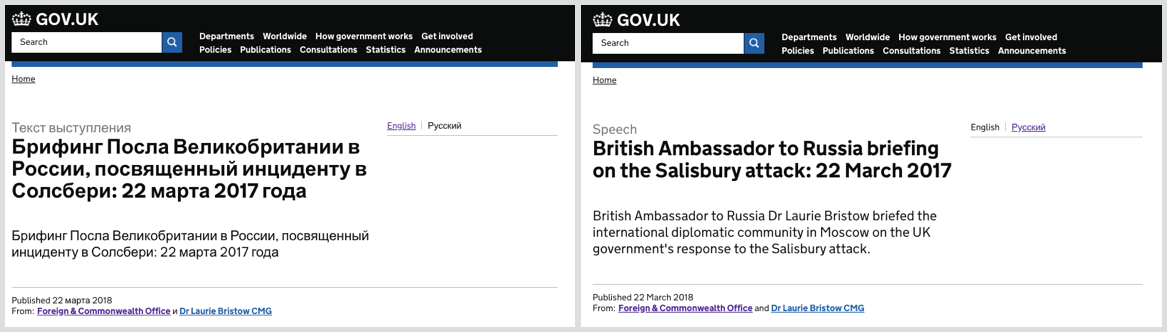

The fact of the “closed briefing,” to use Kommersant’s phrase, was confirmed by the Twitter feed of the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO). This tweeted the following post on March 22, 2018 — the date given in Slide 1.

Ambassador Laurie Bristow @UkinRussia is hosting a briefing for the diplomatic community based in Moscow to update on latest developments following the #Skripal incident in Salisbury. pic.twitter.com/yqn3lSs56y

— Foreign Office 🇬🇧 (@foreignoffice) 22 марта 2018 г.

The Embassy’s Facebook page (archived here) added a number of details, including that the briefing was presented to “over 80 representatives of the diplomatic corps.”

The British and Kommersant accounts thus agree that the briefing was given to the diplomatic community in Moscow by the British ambassador. Such a meeting, gathering various and unspecified diplomats of various nationalities in an Embassy, would likely be closed to the public and the press.

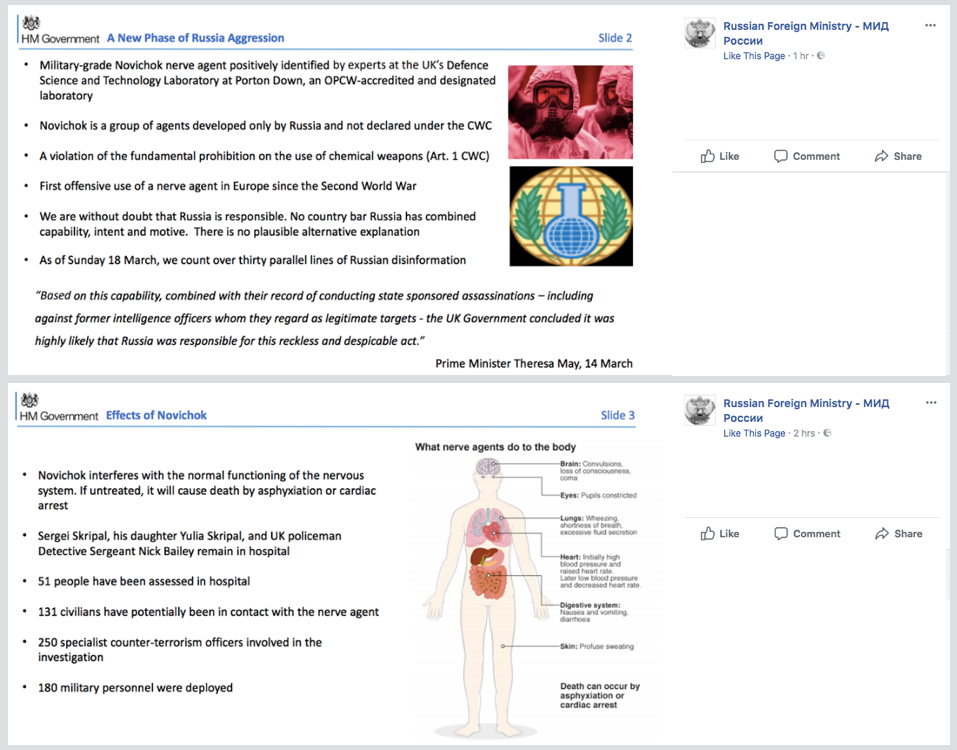

The MFA’s account of “classified” files, however, appears incorrect. For one thing, the slides themselves have no classification marking; if they had been secret (as the MFA’s Russian-language post stated), they would be marked as such, most likely with the word SECRET in block capitals.

Since the briefing was, by definition, to non-British nationals, apparently from a large number of countries, the classification would likely be SECRET RELEASABLE TO [insert country names here].

No such markings are visible on the slides.

A second weakness is that the English and Russian versions of the ambassador’s speech were posted online the same day, and hosted on the UK government’s official website, gov.uk. RELEASABLE TO INTERNET is not a recognized security classification.

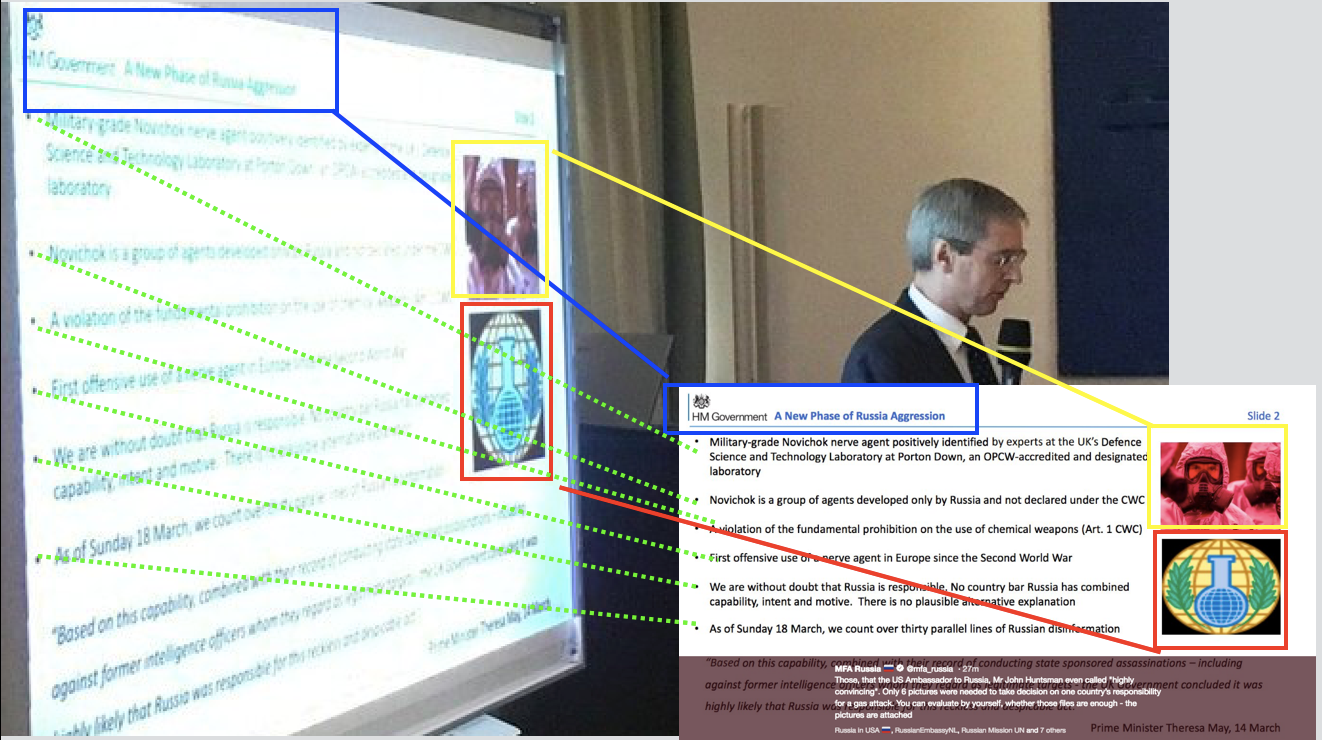

Yet further evidence emerged from the MFA’s own posts. The third slide it shared is identical with the slide visible behind the ambassador’s shoulder, in the tweet published by the FCO before this narrative from the Russians emerged.

The layout, text and images match exactly; the visible wording confirms the match. Thus, at least one slide from the “notorious classified files” was tweeted by the FCO to its more than 800,000 followers five days prior the MFA publication.

Conclusion

This incident is small in itself, but it fits a larger pattern. The MFA took a Kommersant article which seems to have reported accurately on the nature of the meeting, and misinterpreted it as a report on the nature of the file itself.

That misinterpretation then allowed the MFA to cast doubt on the entire basis of the British accusations against the Kremlin: “The notorious classified files, that were the ground for the decision taken by the US & EU countries to deport Russian diplomats… Only 6 pictures were needed to take decision on one country’s responsibility for a gas attack.”

Of the key disinformation tactics of dismiss, distort, distract, and dismay used by official Russian platforms, this was a case study in the use of distortion to achieve a rhetorical effect.

By Ben Nimmo, for DFRLab

Ben Nimmo is Senior Fellow for Information Defense at the Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensic Research Lab (@DFRLab).