By Polygraph

“In the early 90s the Baltic nations, after over 50 years of being a part of the #SovietUnion, gained their national independence. This event raised hopes and aspirations that the Baltic Soviet Republics would turn into modern democratic and rule-of-law states, which, unfortunately, never came true.”

False

By all metrics, the Baltic states are democratic, law-based nations

On the eve of the 80th anniversary of the outbreak of the Second World War on September 1, 1939, Russia’s Foreign Ministry tweeted out an extract from a joint report titled “The Heritage of WWII in the Baltic States”.

That extract read: “In the early 90s the Baltic nations gained their national independence. This event raised hopes & aspirations the Baltic Soviet Republics would turn into modern democratic & rule-of-law states, which, unfortunately, never came true.”

❗In the early 90s the Baltic nations gained their national independence.This event raised hopes & aspirations the Baltic Soviet Republics would turn into modern democratic & rule-of-law states, which, unfortunately, never came true. 📗Read the full text🔗https://t.co/aA90iu05sQ pic.twitter.com/xtOsMRDT9M

— MFA Russia 🇷🇺 (@mfa_russia) August 27, 2019

Experts, former politicians and diplomats strongly contest the Russian Foreign ministry’s assertion.

“Russia’s claim that the Baltic nations never turned into modern, democratic and rule-of-law states is patently false. It is ridiculous that anyone in the Russian Foreign Ministry would claim that,” Matthew Bryza, former U.S. Ambassador to Azerbaijan told Polygraph.info.

Forever with our Baltic Allies/Friends/Family!! https://t.co/PS3o3d6GXr

— Matthew Bryza (@BryzaMatthew) July 23, 2015

Bryza, who was previously director of the International Center for Defense and Security, a Tallinn-based think tank, said that Estonia “is one of the most dynamic, modern, rule-of-law countries in all of the European Union.”

Former Estonian President Toomas Hendrik Ilves mirrored that sentiment, telling Polygraph.info Estonia is “by far the least corrupt post-communist country.”

Ilves said the Russian Foreign Ministry was merely “rehashing” the same baseless arguments Russia has been making for 28 years, adding the Baltic states “wouldn’t’ have been admitted to NATO or the EU if [Russia’s claims] had any merit.”

Ilves was referring to the so-called Copenhagen criteria, which determine who is eligible to join the European Union, and criteria for a North Atlantic Treaty Organization Membership Action Plan.

Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania joined the EU and NATO in 2004.

Let’s celebrate the 30th anniv. of the Baltic Way! #OTD 30 yrs ago 2 mil. people united in their drive for freedom & formed 600km human chain in Estonia, Latvia & Lithuania to condemn the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact & demand restoration of the 🇪🇪 🇱🇻 🇱🇹 independence #BalticWay30 #NATO pic.twitter.com/EoxaHbHobK

— Lithuania in NATO (@LitdelNATO) August 23, 2019

The EU requires that any potential member have “stable institutions guaranteeing democracy, the rule of law, human rights and respect for and protection of minorities.”

NATO only invites aspiring members that have, among other things, “built a democratic system of governance and a market economy.”

Aliide Naylor, a writer-in-residence at the Latvia-based International Writers’ and Translators’ House and the author of the book “The Shadow in the East: Vladimir Putin and the New Baltic Front,” likewise called the Russian Foreign Ministry’s claim “untrue and wildly hypocritical.”

“The three Baltic nations have varying degrees of democracy, ‘modernity’, freedom, and corruption,” Naylor told Polygraph.info. “But according to the 2019 [Freedom House] Freedom in the World report, Estonia ranks at 94/100 – a better score than both the U.S. and the U.K. [Latvia was ranked 87 out of 100 and Lithuania 91 out of 100, with 100 meaning most free]. Like any other nation, they still struggle with imperfect political processes, but to say they never turned into modern and democratic states is silly.”

“Later this year, similar fireworks displays will also be held to mark the Tallinn Offensive on Sept. 22 and the Riga Offensive on Oct. 13” #Estonia #Latvia #Lithuania https://t.co/9WlVkjbiPg

— Aliide (@Aliide_N) July 9, 2019

Many international organizations have made similar assessment of the Baltic nations’ democratic bona fides.

Freedom House, a U.S. government-funded think tank that conducts research and advocacy on democracy and related issues, counted Estonia, Lithuania and Latvia among “consolidated democracies” in its 2018 Nations in Transit 2018 report.

That report, which tracked the progress of the former Soviet states, found that 19 of the 29 countries had declines in their overall democracy scores.

Freedom House called Estonia one of “three bright spots,” and raised Estonia’s National Democratic Governance rating from 2.25 to 2.00 (1 – most democratic, 7 – least democratic), citing its “demonstrated resilience and impartiality of national institutions, as well as respect for institutions by all major stakeholders, after the change of government in November 2016.”

Estonia’s democratic governance and corruption ratings also improved.

Latvia, which Freedom House found to have “continued on its path to becoming a stable north European democracy,” did see its Civil Society score drop, in part because of the rise of illiberal groups. Freedom House also lowered Lithuania’s Civil Society rating, calling corruption the biggest threat to democracy there.

The German-based Bertelsmann Stiftung Foundation’s Transformation Index (BTI), which analyzes and evaluates successes and setbacks on the path toward a democracy based on the rule of law and a socially responsible market economy, found all three Baltic states to be democracies in consolidation.

The BTI ranked Latvia eighth out of 129 countries analyzed for its quality of democracy, market economy and political management, noting that the Baltic country has “free and fair parliamentary and local elections.”

The BTI ranked Lithuania in fourth place, saying it has “no constraints on free and fair elections,” while Estonia took the top spot.

“Elections in Estonia are free, fair and meaningful in the sense of determining public policies and filling political positions,” the BTI found.

‘All states have flaws’

In terms of the media environment, the press freedom watchdog Reporters Without Borders (RSF) ranked Estonia 11th its 2019 World Press Freedom Index, while Latvia came in 24th and Lithuania placed 30th. RSF’s annual reports cover 180 countries.

“Estonia has a freer press than the U.K. and Germany, according to RSF (although in the present more ‘far-right’ climate with [the Conservative People’s Party of Estonia] in government, some outspoken liberal journalists may challenge this perceived notion of free press), Naylor said. “Latvia and Lithuania are also doing better than the U.S. and U.K. in terms of press freedom, by these measures.”

RSF ranked Germany 13th in terms of press freedom, France 32nd, the U.K. 33rd and the U.S. 48th. It ranked Russia 149th.

The Berlin-based anti-corruption NGO Transparency International (TI) compiles a Corruption Perception Index that ranks countries on a scale of 0-100 (0 being maximally corrupt and 100 being maximally clean). On its 2018 Corruption Perception Index, Latvia scored 58, Lithuania 59 and Estonia 73 – respectively, 41st, 38th and 18th out of 180 countries.

TI gave Russia a score of 28, putting it in 138th place globally.

Vaidas Saldžiūnas, a Lithuanian journalist who writes extensively on defense and security-related issues, told Polygraph.info that even less positive assessments still painted the Baltic states in a mostly positive light.

“What comes to my mind first, based on such criteria, is the (Economist Intelligence Unit) Democracy Index 2018. There Estonia is 23rd, Lithuania 36th, Latvia – 38,” he said.

The Economist Intelligence Unit describes the Baltic states as “flawed democracies.”

Democracy is in danger around the world. Our foreign editor, Robert Guest, explains what the Economist Intelligence Unit has uncovered in this year’s Democracy Index pic.twitter.com/sETUeuJXxH

— The Economist (@TheEconomist) January 9, 2019

Saldžiūnas said that while those less-than-perfect scores are “probably not enough” for critics, they aren’t really “news” given that all states have flaws: “Greece, the birthplace of democracy is behind, the Unites States isn’t on the top, yet we are still ahead of 130-plus countries. But when the critique comes from Russia, which is not a beacon of democracy and rule of law (144, behind Kazakhstan and Afghanistan), that says a lot. The international community in various statements recognize [the] Baltic nations as modern, democratic, rule-of-law-based states, which allows for membership in various international organizations.”

Loss and projection

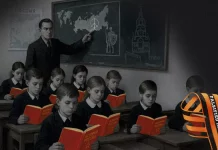

Dalia Bankauskaitė, a lecturer with Vilnius University’s Faculty of Communication, told Polygraph.info that it is widely believed Russia resents having lost control of its neighbors. This, she said, best explains Moscow’s attitude towards the Baltics.

“I would like to quote what a young Lithuanian said during one of our discussions,” Bankauskaitė said. “‘Why can’t the Kremlin leave us alone? The divorce happened long, long ago. We live our life … Mind your own country’.”

Analysts argue the answer to that question is connected to the current Russian regime’s survival strategy.

Bryza said President Vladimir Putin is “obsessed with extinguishing any movement towards democracy and rule-based politics in Russia that could threaten his own rule.”

“Any Russian who has visited the Baltics knows how much more advanced those Baltic countries are compared with Russia on developing democracy and the rule of law,” Bryza said. “So I think President Putin is trying to discredit the historical record of success of the Baltic countries to protect himself.”

Ilves said that the Kremlin, which has no ideology apart from the “ideology of expediency,” is simply trying to amplify the message that it does not want to follow the “fake rules of Western liberal democracy.”

Ilves argues the Baltic states’ post-Soviet transformation “undermines the fundamental lie of the Kremlin” that countries can become liberal, democratic and rule-of-law based nations after exiting Moscow’s orbit.

Saldžiūnas believes the Baltic states’ success undermines “the core of the Kremlin lie” that they cannot survive without Russia.

This deeply stupid and nasty campaign is an embarrassment for the Russian government https://t.co/NchQjQEIZC

— C. Stelzenmüller (@ConStelz) August 31, 2019

“When you say that the Baltic states will fail without Russia (those were actual slogans in late Eighties and early Nineties) and now the facts are proving you wrong (GDP, income, democracy, freedom indexes, etc.), it’s bad for your own image. So what do you do? You don’t let the facts spoil a good propaganda piece,” he said.

According to Saldžiūnas, this leaves Russia in the position of having to soothe its domestic audience with these falsehoods, given that Russia itself “has failed in democracy and has but a façade of it, just like [it has a façade of] the rule of law.”

Naylor said she thinks many Russians assume that every country functions like their own, adding that Moscow’s claim that it is the Baltic states, and not Russia, which have failed to turn into modern, democratic, and rule-of-law states, “could be a form of projection at play.”

“There could also be envy at the comparative progress, or resentment about the role they [the Baltic states] played in the Soviet collapse,” she said.

Bankauskaitė likewise says that by portraying the Baltic states as “failing states,” the Russian government seeks to make Russians believe that it’s not worth emulating their example and nothing good came from the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Ok, let’s analyse this, shall we.

Press Freedom Index 2019:

Estonia, 11th

Latvia, 24th

Lithuania, 30th

Russia…. 149thCorruption Perceptions Index 2018:

Estonia, 18th

Lithuania, 38th

Latvia, 41st

Russia… 138thGo home, @mfa_russia, you’re drunk. https://t.co/2TxngXIBrn

— Paul Niland (@PaulNiland) September 1, 2019

“The Kremlin’s disinformation never speaks about Russia, it always talks about others in a negative way … I have never seen/read/heard pro-Kremlin media or Kremlin institutions talk positively about Russian civic initiatives,” she said.

“Russia and the Kremlin should never be confused,” Bankauskaitė added. “Russian society itself is a victim of Putin’s regime.”

By Polygraph