By Oleksandr Danylyuk, for International Policy Digest

The exposure of a journalist of the German magazine, Der Spiegel, Claas Relotius, who falsified materials for his articles, was a real shock and sharply raised the issue of the availability of effective tools for controlling misinformation in the media community.

Relotius’ case is impressive. He managed not only to fool his readers and colleagues over the years but also spread lies and fabrications. He made a brilliant career and achieved a high degree of professional recognition. The winner of the European Press Award in 2017, the CNN Award in 2014, the German Reporter Award in 2013, 2015, 2016, 2018, Claas Relotius admitted that at least 14 of his reports were fake. Some of them were also nominated for and received journalism awards.

It is noteworthy that even after the exposure of Relotius, the management of Der Spiegel supported him for some time, stating that the journalist had become a victim of slander, and only after the emergence of irrefutable evidence, was forced to admit deception. In December 2018, Relotius was dismissed from Der Spiegel and his numerous journalistic awards were withdrawn.

The scandal became geopolitical after the US ambassador to Germany, Richard Grenell, in an open letter accused Der Spiegel of “anti-Americanism” and actual support of Relotius in inventing negative stories about the United States, which constituted an essential part of his reports. Grenell also called for an independent investigation into the breach of journalistic standards by the Der Spiegel editorial board, which did not carry out any verification of the facts contained in Relotius’s articles nor those by other journalists. In his reply, the editor-in-chief of the magazine acknowledged the violation of standards but denied the existence of any anti-American bias on the editorial board.

Criticism of Der Spiegel’s political scandals were once loud but today are forgotten. In the early 1960s, the magazine published a series of investigations by journalist Conrad Ahlers, who severely criticized and accused the then German Defense Minister Franz Josef Strauss, who was also chairman of the Christian Social Union, a key German center-right party, of unprofessionalism and corruption. The peak of the confrontation was in October 1962 after the publication by the magazine that the Defense Ministry, according to the Federal Republic of Germany, was allegedly unprepared for Soviet aggression. The consequences of the scandal, known as Spiegel-Affäre, led to the reformation of the parliamentary coalition and Straus’s resignation.

According to the Soviet Foreign Intelligence Officer, Ilya Dzhirkvelov, who defected to the West, the conflict between Strauss and Der Spiegel was part of a Soviet special operation aimed at discrediting Strauss, who might have become the next chancellor of West Germany. It is not certain that there were any formal relationship between Conrad Ahlers and the Soviet secret services, but he apparently had his own political interests. He was an activist in the opposition Social-Democratic Party. After coming to power, he initially led the press office of Chancellor Willy Brandt, and then became the Secretary of State for Press and Information.

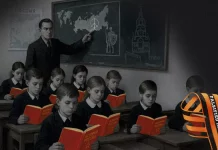

This case was not unique. The USSR consistently sought opportunities to penetrate Western media that were urgently needed for effective influence operations in the so-called “active measures.” In the KGB was even a special department engaged in recruitment and infiltration of the media created in the West by Russian and Soviet immigrants. However, the main priority of the Soviet special services, according to the words of the former head of the Soviet foreign intelligence, General Oleg Kalugin, was the infiltration of its own agents into Radio Liberty.

The large number of only the exposed Soviet agents among journalists of Radio Liberty, testifies to the industrial scale of this infiltration. The most successful of the disclosed agents was the KGB agent, Oleg Tumanov, who until 1986 worked as the editor-in-chief of the Russian service of Radio Liberty and had a direct impact not only editorially but also on the personnel policy of the service. For eight years he has been responsible for the appointment of each employee of the Russian Service of the radio. His wife, Olga Tumanova, a former BBC journalist who later became a Russian language teacher at a US intelligence school in Europe, also worked for the Soviet secret services.

It is noteworthy that Oleg Tumanov as well as another Soviet agent, Yuri Marin, who was also an employee of Radio Liberty, was not disclosed by American counterintelligence, and their cooperation with the KGB became known only after their escape to the USSR.

Infiltration of Radio Liberty involved the intelligence services of other member states of the Warsaw Bloc. Among the well-known Soviet agents on the radio, Andrzej Chekhovich, Pavel Menarzhyk, and Khristаn Khristov, who worked respectively on Soviet intelligence in Poland, Czechoslovakia, and Bulgaria, should be especially noted. After returning to the Soviet bloc countries, their testimony describing the spy and manipulative nature of Radio Liberty’s activity became the basis for a broad international campaign to discredit the radio.

Despite the popular belief in the 1990s, that with the collapse of the USSR, the practice of sending and using agents to Radio Liberty and other Western media was completed, the Russian intelligence services did not recall existing agents, and with a high probability continued to build up their own capabilities there. This practice was also supported by the fact that there was less attention by Western counterintelligence, which, as we see, was not too successful in identifying Soviet agents in the media even during the Cold War years.

There were many scandals associated with the sudden change of values by journalists in the Western media in former Soviet countries. For example, Anna Herman, the former head of Radio Liberty’s bureau in Kyiv, who, after many years of working in democratic western media, unexpectedly joined the authoritarian pro-Russian camp of the President Viktor Yanukovych, where she quickly became one of the leaders. Today the Russian journalist, Andriy Babitsky, has been working with Radio Svoboda since 1989, and since 2009 he has been the editor of “Echo of the Caucasus” (Russian-language Radio Liberty project broadcast in Georgia). The “Echo of the Caucasus” soon became the subject of sharp criticism for the use of Russian narratives in assessing Georgian-Ossetian and Georgian-Abkhazian conflicts, as well as Russian aggression against Georgia in 2008.

Despite this, Andriy Babitsky continued to work and was fired from Radio Svoboda only in 2014 after publicly supporting Russian aggression against Ukraine. After his dismissal, Babitsky helped to create a television channel in the territory of Russia-occupied Donbass and then began working on the famous Russian propaganda channel LIFE.

Of course, all these cases can be considered to be coincidences. However, in the context of the hybrid warfare, when respectable and trusted Western mass media are so critical for generating public opinion, the importance of the infiltration of media, the recruitment of journalists, editors and publishers cannot be neglected.

The main issue today should not be the violation of the standards of journalism by Claas Relotius, but his motivation to violate them, as well as the motivation of jury members of various journalistic awards to appreciate his “fake news” so highly. Of course, the jury of such awards, as a rule, includes honoured and well-known journalists. However, Relotius was respected until he was exposed.

This article was originally published in International Policy Digest