Over the past two decades, the internet has rewired civil society in unprecedented ways, propelling collective action to a radically new level of citizen autonomy.

Democracy is now not only infrequently exercised at the ballot box, but is lived and experienced online on a day-to-day basis.

Much has been made of the democratizing effect of the internet, and its emancipatory impact on under-represented and marginalized groups living under authoritarian regimes, where it nurtures a networked public sphere that constitutes an independent alternative to tightly controlled media environments.

According to Harvard’s Yochai Benkler, this networked public sphere allows for bottom-up agenda-setting, universal access to information, and freedom from governmental interference. Benkler explains: “The various formats of the networked public sphere provide anyone with an outlet to speak, to inquire, to investigate, without need to access the resources of a major media organization.”

Since more members of society are now encouraged to participate in public discourse and speak up about matters they deem to be of public concern, the internet has rendered the diversity of citizens’ views more salient. This is particularly visible when there is conflict and disagreement between different political or civic interest groups. Whenever there is a controversial policy announcement, there will always be a highly motivated group of people who use the internet to apply enormous pressure on politicians in these moments by voicing their discontent.

Democratic bodies are typically elected in periods of three to five years, yet citizen opinions seem to fluctuate daily and sometimes these mood swings grow to enormous proportions. When thousands of people all start tweeting about the same subject on the same day, you know that something is up. With so much dynamic and salient political diversity in the electorate, how can policy-makers ever reach a consensus that could satisfy everyone? If our representatives are unable to keep up with digital expressions of citizen sentiment, does that mean that we have become ungovernable by the institutions that exist today?

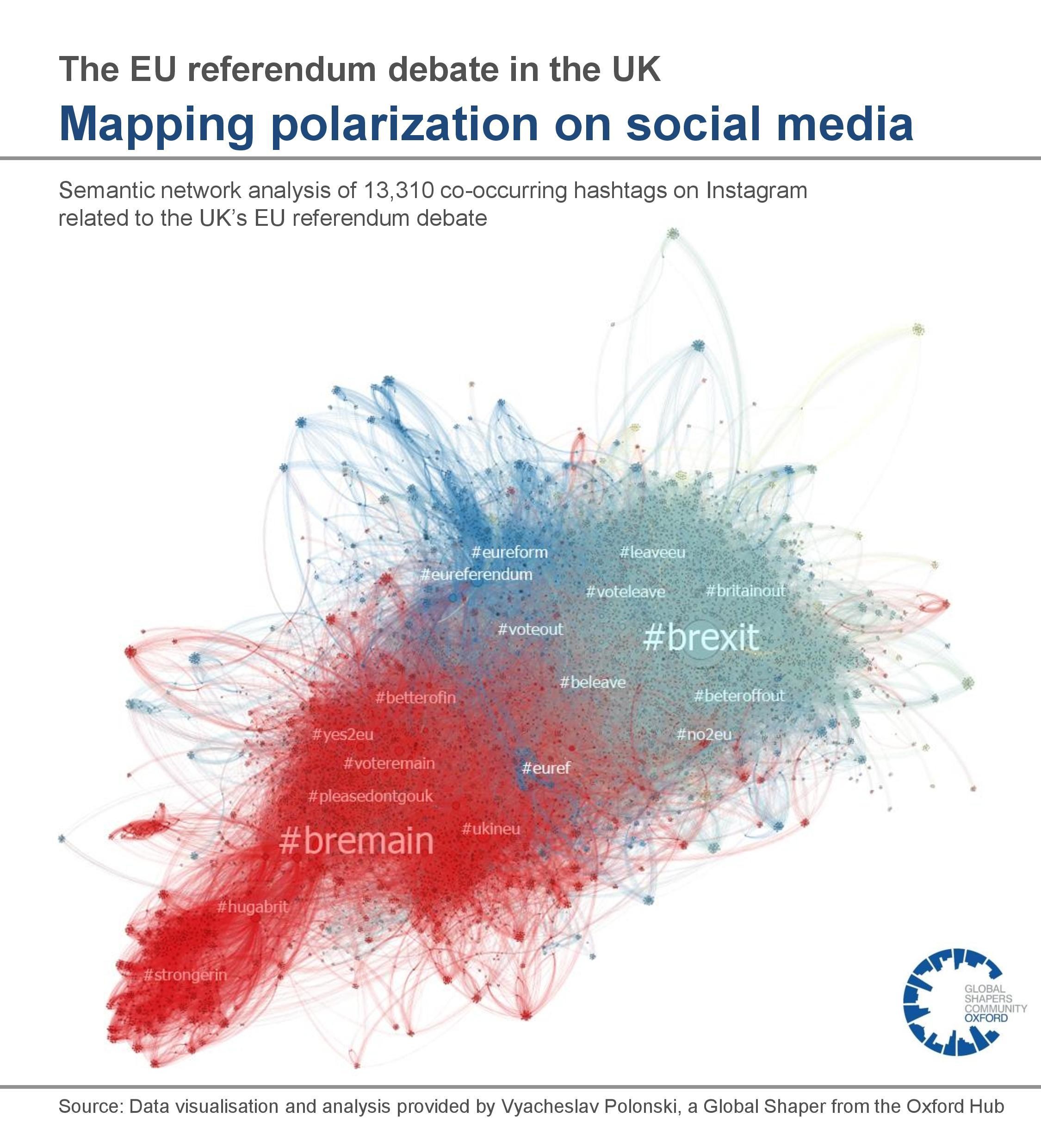

At the same time, it would be a grave mistake to discount the voices of the internet as something that has no connection to real political situations. Last month, British politicians and activists campaigning for Britain to remain in the EU in the recent referendum had to learn this lesson the hard way.

What happened in the UK was not only a political disaster, but also a vivid example of what happens when you combine the uncontrollable power of the internet with a lingering visceral feeling that ordinary people have lost control of the politics that shape their lives. When people feel their democratic representatives do not serve them anymore, they turn to the internet. They look for others who feel the same and moans turn into movements.

In this regard, the Leave campaign’s main social media messages appealed to the agency of ordinary voters to reject the rule of the bureaucracy and “take control” of their own country. Using very simple language, largely consisting of only a few syllables, these messages spread very fast across the internet and were often reinforced with amusing memes, instead of rigorous expert opinions or statistics.

Polarization as a driver of populism

In light of these recent developments, right-wing populist sentiments have been growing in strength and popularity across both Europe and the US. These movements are fuelled by populist anger, resurgent nationalism, and a deep-rooted hostility towards immigrants.

People who have long entertained right-wing populist ideas, but were never confident enough to voice them openly, are now in a position to connect to like-minded others online and use the internet as a megaphone for their opinions. They become more confident and vigorous, because they see that others share their beliefs. This is concerning, because we know from previous research that increased contact with people who share our views makes our previously held beliefs more extreme. It grants us new group identities that permit us to do things we deemed inconceivable before. In this way, one could argue that the Brexit vote was as much a vote to reclaim one’s political independence as it was a vote to reclaim one’s lost national identity.

The greater diversity and availability of digital content implies that people may choose to only consume content that matches their own worldviews. We choose who to follow and who to befriend. The resulting echo chambers tend to amplify and reinforce our existing opinions, which is dysfunctional for a healthy democratic discourse. And while social media platforms like Facebook and Twitter generally have the power to expose us to politically diverse opinions, research suggests that the filter bubbles they sometimes create are, in fact, exacerbated by the platforms’ personalization algorithms, which are based on our social networks and our previously expressed ideas.

This means that instead of creating an ideal type of a digitally mediated “public agora”, which would allow citizens to voice their concerns and share their hopes, the internet has actually increased conflict and ideological segregation between opposing views, granting a disproportionate amount of clout to the most extreme opinions.

The disintegration of the general will

In political philosophy, the very idea of democracy is based on the principal of the general will, which was proposed by Jean-Jacques Rousseau in the 18th century. Rousseau envisioned that a society needs to be governed by a democratic body that acts according to the imperative will of the people as a whole.

However, Rousseau foresaw in Book IV of the Social Contract that “when particular interests begin to make themselves felt […], the common interest changes and finds opponents: opinion is no longer unanimous; the general will ceases to be the will of all; contradictory views and debates arise; and the best advice is not taken without question.”

The internet, in particular, intensifies the fragmentation of opinions, allowing people who are most passionate, motivated and outspoken to find likeminded others and make themselves heard – as we have seen on social media in the EU referendum.

In a similar vein, sudden attention-grabbing focusing events, such as natural disasters, terrorist attacks or external shocks to the environment, could also sway public opinion and trigger hasty political decisions with potentially unsustainable repercussions. Politicians run the risk of making important policy-decisions based on current emotional bursts in the population or momentary popular opinions, rather than what is best for the country. For instance, important and far-reaching decisions, such as leaving the EU, would need to be approved by qualified two-thirds majorities in multiple plebiscites over several years.

The critical challenge for policy-makers is, therefore, to learn to distinguish when a seemingly popular movement does actually represent the emerging general will of the majority and when it is merely the echo of a loud, but insignificant minority.

Prospects for a future-proof democracy

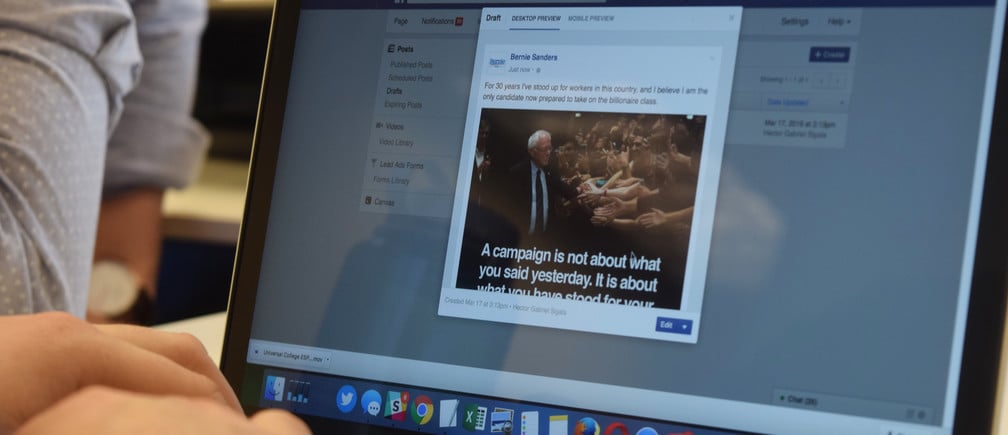

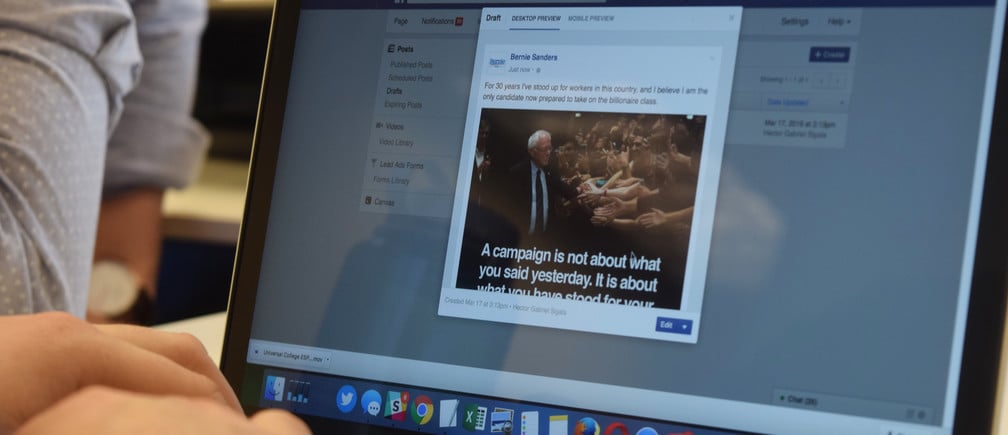

There can be no doubt that a new form of digitally mediated politics is a crucial component of the Fourth Industrial Revolution: the internet is already used for bottom-up agenda-setting, empowering citizens to speak up in a networked public sphere, and pushing the boundaries of the size, sophistication and scope of collective action. In particular, social media has changed the nature of political campaigning and will continue to play an important role in future elections and political campaigns around the world.

However, this technology can also be a platform for conflict and malicious agitation by right-wing populists that are dysfunctional for a healthy democratic discourse, while our current governance systems are susceptible to emotional bursts and populist movements that unfold on the internet. What the EU referendum has taught us is that this accelerating technology is open to all and can be used to influence the public agenda in many different ways. Intimated by the power of internet users, our current governance institutions are, however, incapable of handling the dynamism and diversity of digitally-mediated citizen opinions.

We are thus not ungovernable in the long term, but need to govern ourselves in radically new ways. The only way to accomplish that is by re-imagining the institutions that would allow citizens to engage in enlightened debate in an active and inclusive public sphere.

Written by Vyacheslav Polonski

Network Scientist, Oxford Internet Institute

Source: The World Economic Forum