If we know lots of people on social will only glance at our headlines and not tap through, why can’t we bring better information to them where they are?

This is a great idea: In order to reduce the number of its old stories that get recirculated as new, The Guardian is making a story’s age more prominent, both to readers and to those who might only see a link on social media without clicking through. Here’s Chris Moran:

For some time now we’ve been aware of certain issues around social sharing in particular. Shorn of context like the date, accurate and responsible reporting can mislead. As an example, almost every February we see a sudden spike in referral from Facebook to a six-year-old story about horsemeat in a supermarket’s meat products. Originally published in February 2013, it’s generally discovered via search, the reader notices the month of publication but not the year and kicks off an annual, minor viral moment.

I wrote about this problem back in 2015, when my Twitter feed was filled with RIPs and memoriams to the Nigerian author Chinua Achebe — despite the fact that he’d actually died two years earlier. Back to Moran:

As a direct result of this, and in a drive to improve transparency and contextualise our journalism accurately even off platform, we’ve introduced two specific changes. Firstly, all older news articles on our site will signpost their age even more emphatically. We hope that even readers who are only briefly clicking through will immediately understand that the piece is from the archive rather than recent reporting.

This feels like a crucial and sensible step, but in the age of social sharing it’s also not quite enough. We’ve therefore built on earlier work responding to data showing that many people are unaware of the source of the journalism they read on social media. So now, along with adding our logo to trail pictures used by social and search platforms, we are also clearly featuring the year of publication on any article more than 12 months old.

So if you’re reading this 2015 story headlined “Donald Trump: ban all Muslims entering US,” you’ll see This article is more than 3 years old backed with bright yellow, which should hopefully let you know this isn’t fresh news to share.

And if you spot it on social — assuming the story’s metadata isn’t still being cached; the Twitter linter is your friend — it should appear with the year of publication embedded into the image that travels with it.

Words matter. He reads aloud, “Donald J. Trump is calling for a total and complete shutdown of muslims entering The United States until our country’s representatives can figure out what the hell is going on. We have no choice.” https://t.co/HrRVctZ5Cd

— ALTERHAN (@alterhan) March 17, 2019

So again, this is a great idea, one worth replicating elsewhere. But it’s also a reminder of the power publishers have to use their article metadata to improve public understanding — and how little they use it. When one of your old stories is floating around social media in a way that causes confusion, you can do something about it.

Every publisher’s article pages contain a section of code high up that defines various elements of that page’s metadata — essentially, descriptive elements that social networks, search engines, apps, or anyone else can read to know something about the article. Here’s some of the metadata for that Guardian Trump article. (See the nerd sidebar below if you’re interested in their image overlay methods.)

Every one of those bits of metadata can be changed; if you have a decent CMS, many of them can be changed pretty easily. The most frequently useful ones are part of (or descended from) the Open Graph protocol introduced by Facebook in 2010. For our purposes, they define the headline, image, and description a platform will use to represent an article.

Let’s say an old article of yours is being recirculated in a way that’s harmful. To make up an example: Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro really was stabbed while campaigning last year. But let’s imagine that some people, for whatever reasons, are saying he’s just been stabbed again. It’s not hard to imagine that an old Economist or BBC story, with an accurate-at-the-time headline, could be recirculated to negative effect:

Jair Bolsonaro is stabbed at a rallyhttps://t.co/l4zmZERRU1

— merryjun (@merryjun1260) October 1, 2018

BBC News – Brazil’s Jair Bolsonaro ‘lost 40% of blood in stabbing’ https://t.co/M3jOHN5GHr

— Peter Palumbo (@PeterPalumbo1) March 21, 2019

But if a publisher sees this happening, they could follow the Guardian model but on a story-by-story basis — changing the story’s metadata to point to a version of the image with a note of its age added.

Heck, you could do it in another language if that’s where the misinformation is spreading.

Or you could rewrite the metadata headline to emphasize it’s not a new story.

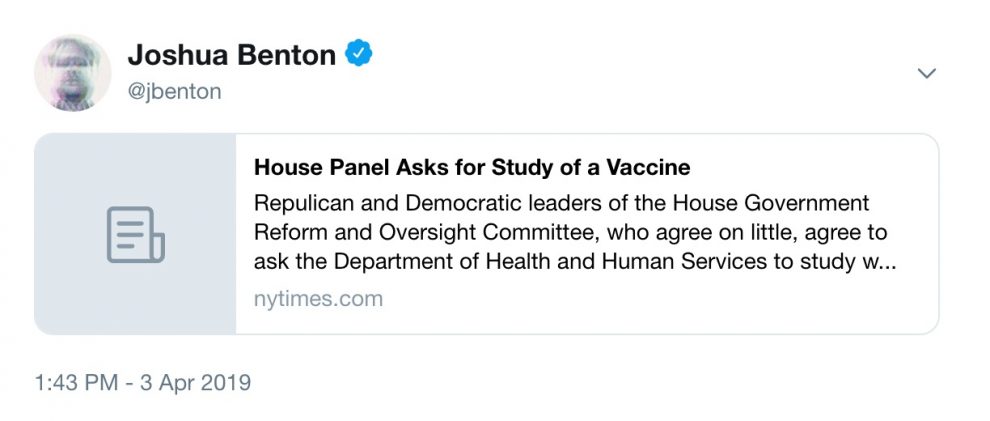

In a more dramatic case, you could go farther. Take this New York Times story from 2000 headlined “House Panel Asks for Study of a Vaccine.” (“After a long and contentious hearing, Republican and Democratic leaders of the House Government Reform and Oversight Committee, who agreed on little else, agreed today to ask the Department of Health and Human Services to study whether vaccination caused a small number of cases of autism.”) Share it on Twitter today and you don’t get an image (there was no Open Graph in 2000!) — but you do get something that could make someone absent-mindedly scrolling think Congress is treating this as an issue that needs more study.

A couple of quick changes to the metadata and you get a forceful rejection of a dangerous piece of health misinformation.

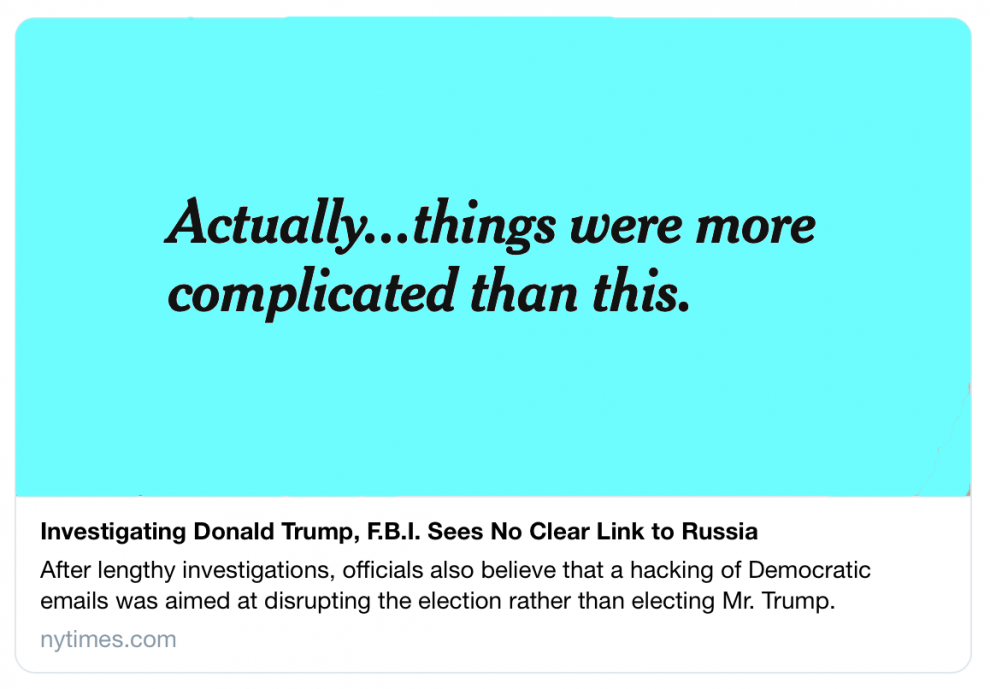

Or imagine a story that turned out to be less than perfectly reflective of reality. You could change the social presentation of it without altering the historical record back at your URL.

Things don’t need to rise to life-or-death stakes for social metadata to provide useful information to an audience. What if a liveblog of a rapidly moving event could indicate how recently it’s been updated?

Or if, on an election night, the image reflected the latest results?

It’s easy to think of other uses. A set of updating bullet points during breaking news. A sports preview story that gets updated with the final score. A tweet pinned to the top of your feed that always lists your site’s current top headlines. A weather or traffic tweet that updates as conditions change. And the great thing is that, unless your CMS is garbage, you should be able to update any of these elements for social while keeping them distinct from what people visiting your site see.

Is this the sort of thing that should be at the core of publisher’s toolbox? Nope. Publishers are generally reducing their investment in social, not increasing it; swapping out JPGs is probably not the most productive way to spend your day. But for special occasions — or for the very real cases where a story’s presence on social misinforms more than it informs — it’s worth thinking about.

Journalists complain all the time about how people don’t clickthrough — they just see a headline or a picture in a scrolling feed somewhere and get left with a limited or warped view. Well, that’s true. But that doesn’t mean we can’t do anything about it.