No matter who wins the White House race, Russia’s anti-Americanism will eventually exhaust itself,

Not since the Cold War Russia has Russia had so much attention in the US elections, arguably being the “hottest” issue of the 2016 electoral cycle. Throughout the presidential debates, Putin and Russia were mentioned more than any other subject. Still, the US is nowhere near Russia when it comes to “caring” about its respected partner. Indeed, Russia’s “love” for the US is unprecedented.

Over the past few years, anti-Americanism has become an integral part of any debate on foreign and domestic policy in Russia. You could even say that it’s one of the cornerstones of the new quasi-religious conservatism which the Kremlin has constructed since Putin returned for his third presidential term. The “struggle against US hegemony” for the sake of building a “more just” multipolar world is an absolutely dominant discourse. Any Russian foreign policy debate is heavily US focused — whether it is the situation in Russia’s near abroad, the future of Europe, the stability of the Middle East after the Arab Spring or even Russia’s pivot to the east. The United States of America is Russia’s favorite topic — it defines and explains all that you see on the globe today.

Bashing the United States has always been an easy way to get people behind whatever the state was up to

Naturally, what the US did in the past and does today is viewed in a clearly negative light. The US was the first to break international law in Yugoslavia, its opportunism in Iraq lead to the eventual destabilisation of the entire region (and, eventually, the creation of ISIS), the US staged numerous revolutions in neighbouring states during the early 2000s and it promotes decadent and harmful values that destroy nations and bring about the end of the European civilisation as a cultural phenomenon. And of course, Washington was behind the “fascist coup” in Ukraine in 2014 and is now advancing anti-Russian sanctions and propaganda, as well as more “active” measures aimed at reducing Russia’s role in the region and the world — even to the point of regime change or dismantling Russia.

The “US as the worst enemy of Russia” discourse is hardly a new one. A legacy of the Cold War, it was only briefly forgotten in the late 1980s and early 1990s. But since 1995-1996, Russians have started to view the US increasingly as a competitor to Russia. Following the 1999 NATO bombings in Yugoslavia, Russian citizens’ view of the US entered into a downward spiral — this peaked in 2015, with 81% of Russians viewing the US in negative terms.

The “go-to” propagandist move

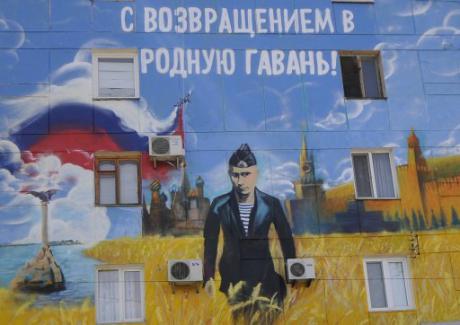

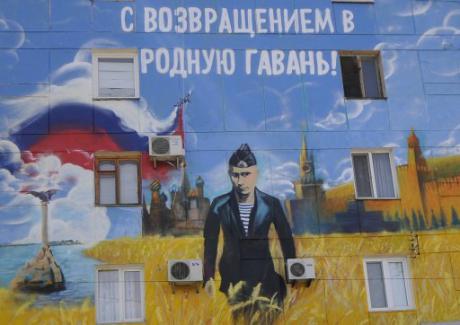

Bashing the United States has always been an easy way to get people behind whatever the state was up to. If you look at Putin’s approval ratings, four of its highest peaks strongly correlate with the heaviest waves of anti-American propaganda in Russia. From NATO actions in Yugoslavia to the war in Iraq, from the 2004 Orange Revolution to the 2008 war with Georgia and after the annexation of Crimea in 2014, anti-Americanism has proven extremely effective in gaining political support for Russia’s leadership.

Contrary to cases when the goal was to prove that some group of people (liberals, for instance) or a nation (Ukraine) are the enemy of the state, it is fairly easy to “discredit” the United States. You only need to refresh existing prejudices by outlining “what awful thing again they are up to now”. As the sole super-power in the world (a fact that Putin confirmed in recently at the St Petersburg International Economic Forum), the United States receive special treatment among Russians.

To some extent, it is both flattering and honourable to be the power that the US is “trying to contain”. Being a target of “US-led conspiracy” confirms one of the main theses of late Putinism that “Russia is back as a big player on the world stage”. And what could possibly be more reassuring than having supposedly the only superpower in the world talking so much about the “Russian threat” and “Putin being always ahead of the game” for making Russia’s return to “USSR” heavyweight status seem credible.

Compensation for the economic hardship that Russian citizens experience can only partially explain such a persistent desire to go along with the anti-American rhetoric. According to the polls, for 59% of Russian surveyed, “great power status” remains one of their primary concerns. In their eyes, the US-Russia confrontation proves that Putin is “making Russia strong again”. Moreover, the explanation that the US is behind all the mess in the world, especially in Ukraine, but also Georgia, Kyrgyzstan and Moldova, is a simple and clear message that “unlocks” all complex processes. By confronting the US, Russia is bringing about a better and more just world which gives Russian citizens some sort of vision of the future — a luxury that they are deprived of when it comes to domestic developments.

How long can Russia’s propaganda play the anti-American card?

This post-Crimean “confrontation” with the US, which is fueled on a daily basis by the propaganda machine, is keeping the Russian public alert and mobilised, although today the anti-Americanism does not produce the same effect as it did in 2014. Over the last two years, negative views of US dropped from 81% (at its highest to 66%) and the number of those who positively view the US rose from 18% to 25%. This shift could be partially explained by exhaustion with the negative TV agenda, general frustration and rebound from the more “emotional” state of response to the developments of 2014-2015 in Ukraine.

The main questions here are: how long can Russia’s propaganda play the anti-American card? Will we see the repetition of the Soviet experience, when, at the end of the USSR’s lifetime, America became the “desired destination” — a place and a system that represented the most desired configuration for Russian citizens themselves.

Better stick to geopolitics

It would be safe today to exclude the possibility of a “foreign policy revolution” that would turn Russia’s overall anti-American agenda around. As a cornerstone of Putin’s foreign policy and promoted worldview, treating the United States as the “cause of all problems” is essential. Thus, the propaganda messaging with regards to the US will remain more or less in the existing framework, no matter who becomes the next US president.

Moreover, contrary to the assessments that came in late 2014 and early 2015, Russia’s economy is not collapsing, but experiencing a slow and manageable decline. To put it simply, there is little chance for a crash that could drastically change the attitudes of the population.

As long as the United States is used to explain the big picture and foreign affairs, Russia’s propaganda machine is in the safe zone

So, there are no considerable reasons to see a drastic decline in negative attitudes towards the United States in Russia. But, there is one nasty detail that could significantly damage the almost perfect anti-American propaganda today.

As long as the United States is used to explain the big picture and foreign affairs (even the decline of oil prices and sanctions), Russia’s propaganda machine is in the safe zone. Sixty percent of Russians believe foreign policy coverage on TV to be the most objective. But what we are noticing now is the growing temptation by various state officials to blame their failures on the US.

Take the case of Samara governor Nikolai Merkushkin, who, when answering the questions about a months-long delay of wages, blamed the US Ambassador to Russia for “heating up” discontent among workers at the Avtovazagregat car plant. This absurdity caused a nationwide reaction, prompting heavy criticism in the media and puzzlement among the majority of social media users. So did the cases of Duma deputy Vadim Soloviev, who blamed the USA for flu epidemics in Russia, or Evgeniy Fedorov, who claimed that the US State Department is responsible for cancellation of reduced fares on transports for Moscow region.

In addition to the mockery of idea that “it is all America’s fault” that is already alive and well on Russian social media and popular Youtube bloggers, some professional groups who protest the economic policies of the state, such as Russia’s truck drivers, reference the absurdity of the idea of pinning all the domestic problems on the USA.

Despite the fact that economic hardship is distributed unevenly in Russia today, it is fair to assume that in the near future we will witness more non-politicised social protests, the participants of which would be less inclined to blame the US for unpaid wages, tax hikes and cuts to benefits. Already today, only 27% of Russians believe TV coverage of domestic affairs — trying to sell the idea that their struggles are America’s fault will not find much support.

By diluting the image of the US as a foreign policy foe that is doing its worst in Syria, Ukraine or anywhere else and making it responsible for ever-growing social concerns at home, Russia’s propaganda machine risks damaging Russians’ belief in the validity of Putin’s foreign policy.

Clearly, this transformation is a question of time. But it may very well warp the propagandists’ favourite topic, as well as make Russians question the worldview that, back in 2014, united 86% of the nation with its leader.

By

Anton Barbashin is a managing editor at Intersection. He writes about Russian foreign and domestic politics, and his articles have appeared in Foreign Affairs, The American Interest, The National Interest and Forbes Russia among other publications