Plus: A lot of junk news on Election Twitter in Michigan, the AP pushes for clarity, and fifth graders get better at B.S. detection.

The growing stream of reporting on and data about fake news, misinformation, partisan content, and news literacy is hard to keep up with. This weekly roundup offers the highlights of what you might have missed.

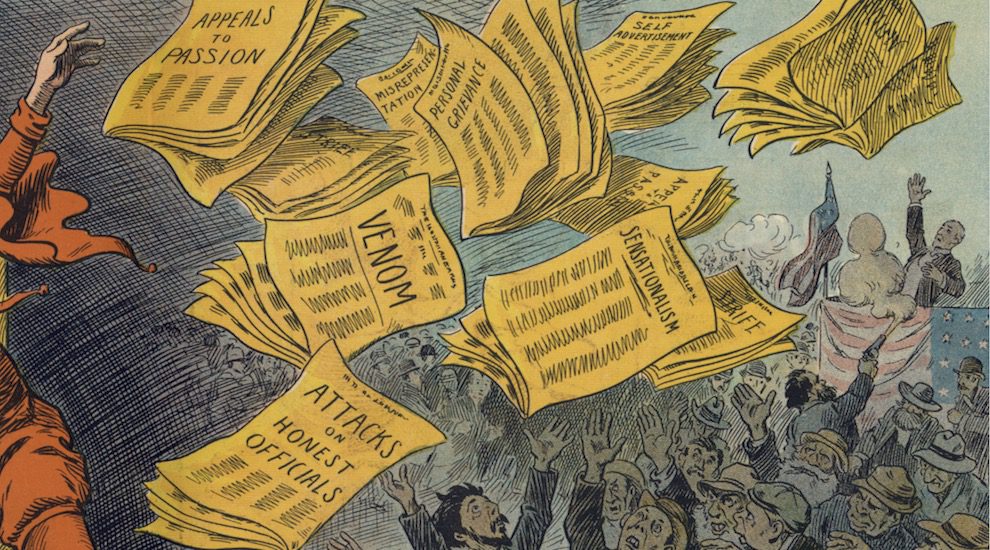

A reminder that fake news is also a problem on Twitter: Facebook gets a lot of the blame, but Twitter users in swing state Michigan shared more “junk news,” “links to unverified WikiLeaks content, and Russian-origin news stories” from November 1–10, 2016 than they did professional news content, according to an Oxford study out this week. (One limitation: The 138,686 tweets by Michigan-based users that the researchers looked at all included some relevant hashtag, and “tweets about the US Presidential Election by individuals in Michigan who did not use one of these hashtags would not have been captured.” Trump-related hashtags, like #CrookedHillary, #DrainTheSwamp, and #lockherup, were used more than twice as often as Clinton-related hashtags like #Clinton, #ImWithHer, and, uh, #factcheck.) Here’s a handy chart from the Financial Times, which covered the research:

“Not only did such junk news ‘outperform’ real news, but the proportion of professional news content being shared hit its lowest point the day before the election,” the study’s authors write.

“All news media outlets are now eyed with suspicion.” A Monmouth University poll of 801 U.S. adults, conducted by phone from March 2–5 found that 27 percent think “traditional major news sources like TV and newspapers” report fake news stories “regularly” and 36 percent say they do so “occasionally”; earlier questions in the survey do not refer to any newspapers by name but specifically mention Fox, MSNBC, and ABC (I wonder if that primed people to think about cable news when answering this question.) Monmouth broke out the results by political party; those who identified as Republicans were significantly more likely to say that traditional news sources “regularly” report fake news (37 percent) than those who identified as Democrats (11 percent).

It’s not Facebook that’s the problem, it’s us: Your thinkpiece of the week comes from danah boyd, principal researcher at Microsoft Research, who argues at Backchannel that the efforts from platforms like Google and Facebook to combat fake news add up to “rounding errors in the ecosystem,” not only because they don’t go far enough but also because the problem is far bigger than some technical challenge. “We’re all trapped up in a larger system that’s deeply flawed…imagine if VCs and funders demanded products and interventions that were designed to bridge social divide. How can we think beyond the immediate and build the social infrastructure for the future? I’m not sure that we have the will, but I think that’s part of the problem.” (You know who else has talked about this: former President Barack Obama.)

But “disputed reports” doesn’t have the same ring to it: The AP updated its stylebook with info on fake news and fact-checking, T. Becket Adams notes at Washington Examiner. You’ll be shocked, shocked to learn that Trump’s tweets do not conform to AP guidelines, which recommend, “Do not label as fake news specific or individual news items that are disputed. If fake news is used in a quote, push for specifics about what is meant. Alternative wording includes false reports, erroneous reports, unverified reports, questionable reports, disputed reports or false reporting, depending on the context.”

How to teach kids about fake news. Fifth-grade teacher Scott Bedley, who was a finalist for California State Teacher of the Year and cohosts an education podcast, wrote in Vox about how he teaches his students to identify fake news. (He pulls material from Newsela, an education technology startup that takes news stories from multiple sources and makes them accessible at different reading levels.) As the students have gotten better at it, Bedley has made the game more complex: “Now that my students have a greater understanding of fake news, our new game for the end of the year will be ‘Fake or Opinion’ instead of ‘Fact or Opinion.’”

Everyone hates April Fool’s Day. “In the era of fake news, it’s best to tread carefully when you and your organization are considering an April Fools’ prank,” Agility PR Solutions advises. In the spirit of the season, here’s a look at the FCC’s rules on broadcast hoaxes and how they might apply to Pizzagate.

Hot take: Fake News Killed April 1st News Gags h/t @mccanner

— emily bell (@emilybell) March 29, 2017

You can also be thankful that it’s on a Saturday this year (followed by International Fact-Checking Day, which comes complete with trivia night questions, on Sunday!)