By @DFRLab

A Russian-based information operation used fake accounts, forged documents, and dozens of online platforms to spread stories that attacked Western interests and unity. Its size and complexity indicated that it was conducted by a persistent, sophisticated, and well-resourced actor, possibly an intelligence operation.

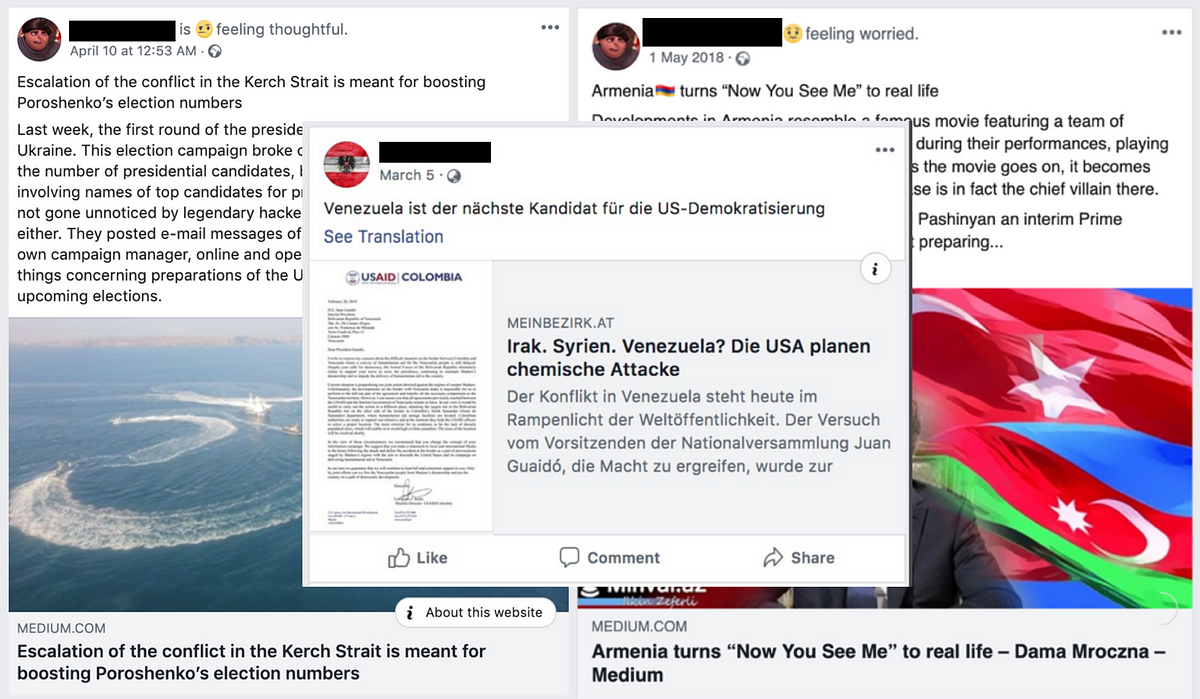

The operation shows online platforms’ ongoing vulnerability to disinformation campaigns. Far more than on Facebook, which exposed it, or Twitter, the operation maintained fake accounts on platforms such Medium and Reddit, and online forums from Australia to Austria and from Spain to San Francisco. Its level of ambition was very high, but its impact was almost always low.

On May 6, 2019, Facebook announced that it had taken down “16 accounts, four pages, and one Instagram account as part of a small network emanating from Russia.” Facebook shared the names (expressed as unique user ID numbers) of the accounts it assessed as involved in coordinated inauthentic behavior shortly before the takedown. Working outwards from those accounts, the DFRLab identified a much larger operation that ran across many platforms, languages, and subjects but consistently used the same approach and concealment techniques.

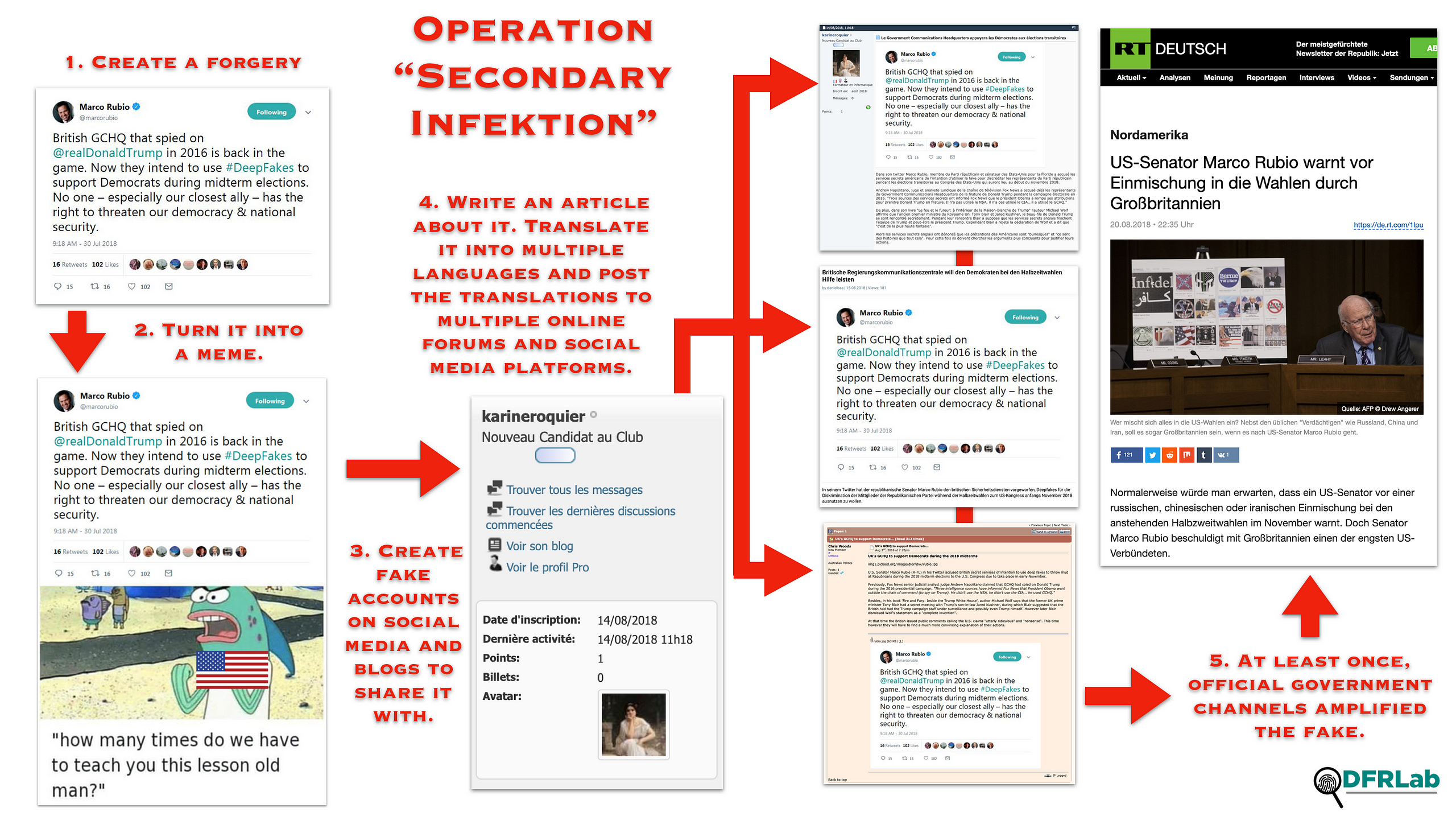

The operation was strongly reminiscent of the Soviet-era “Operation Infektion” that accused the United States of creating the AIDS virus. That operation planted the fake story in distant media before amplifying it through Soviet channels: it ultimately spread through genuine news media around the world and was often reported as fact. The latest operation — which the DFRLab has dubbed “Secondary Infektion” — used a similar technique by planting false stories on the far reaches of the internet before amplifying them with Facebook accounts run from Russia.

The operation’s goal appears to have been to divide, discredit, and distract Western countries. Some of its stories were calculated to inflame tensions between NATO allies, especially Germany and the United States, as well as Britain and the United States. Others appeared designed to stoke racial, religious, or political hatred, especially in Northern Ireland. Few posts gained traction, but one anti-immigrant story penetrated the German far right and continues to circulate online. It appears likely that the Russian operation fabricated the entire story, including its spurious “evidence.” This was a particularly disturbing case of weaponized hatred stemming from a foreign operation.

This article highlights the operation’s most important features. The accompanying posts analyze specific stories on fake assassination plans, Northern Ireland, Russia and Ukraine, Germany and immigration, the European Parliament elections, Venezuela, and a rare account that posted repeatedly.

Operated from Russia

While the DFRLab does not receive access to Facebook’s backend data, contextual and linguistic points helped to corroborate Facebook’s attribution to a likely Russian source.

Many of the operation’s stories focused on geopolitical incidents in Russia’s neighborhood and interpreted them from the Kremlin’s standpoint. Numerous posts attacked Ukraine and its pro-Western government. Some focused on Kremlin allies such as Venezuela and Syria, while others took aim at political events in neighboring countries such as Armenia and Azerbaijan.

One particularly striking story, based on an apparently forged letter, made the remarkable claim that the European Commission had asked a European educational group focused on the crimes of totalitarianism not to award a prize to Russian anti-corruption campaigner Alexei Navalny, calling him an “odious nationalist with explicitly right-wing views.” The letter proposed nominating a Russian Communist instead.

The operation’s content repeatedly featured language errors characteristic of Russian speakers, such as uncertainty over the use of the and a and of the genitive, incorrect word order, and verbatim translations of Russian idioms into non-idiomatic English. For example:

“Current situation is jeopardizing our joint action directed against the regime of usurper Maduro.”

“Why the Democrats collude with Ukraine?”

“As the saying runs, there is a shard of truth in every joke.”

These factors support Facebook’s assessment that the operation originated in Russia.

Far More Than Facebook

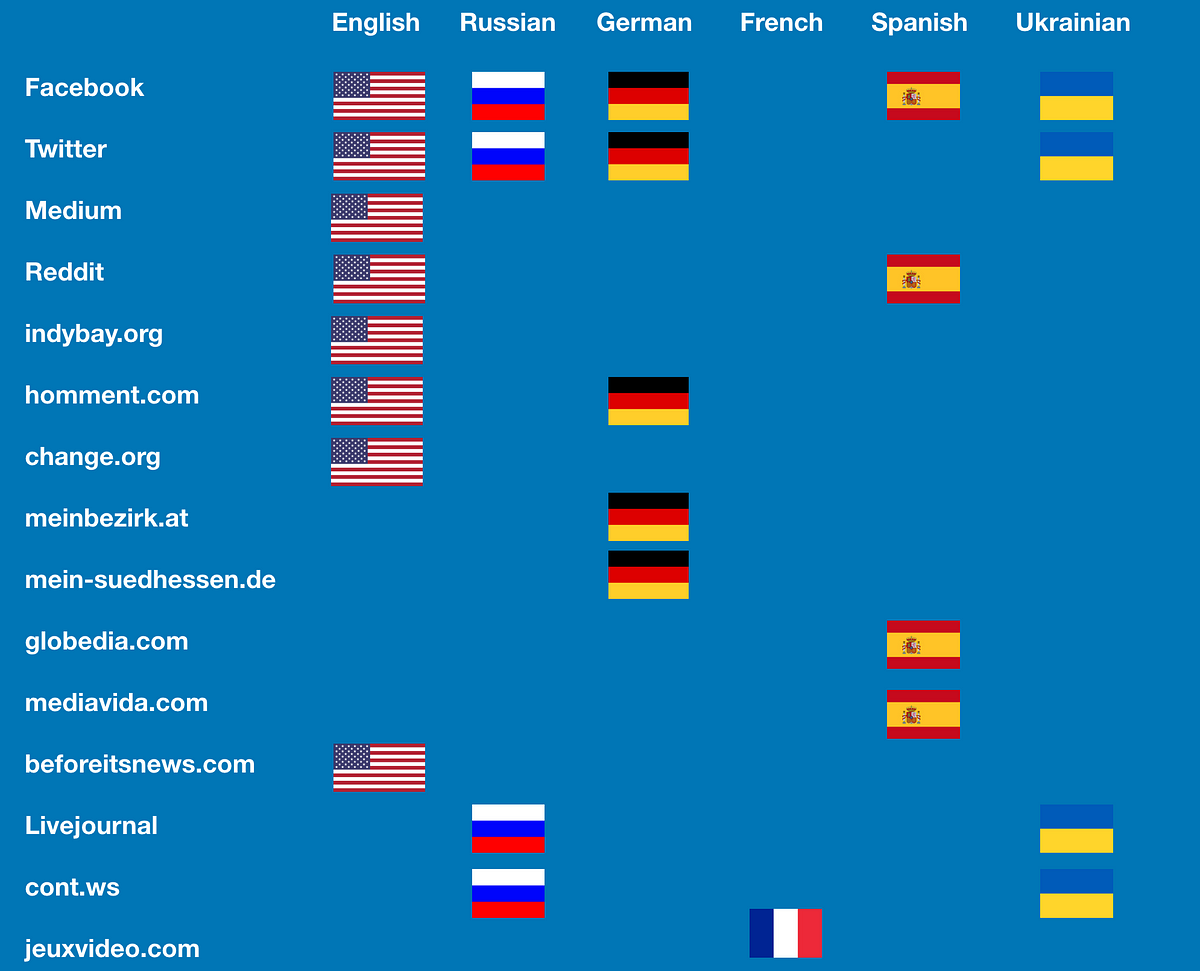

The operation reached far beyond Facebook: it focused on internet platforms around the world. Medium was a particularly frequent target, as were the online forums homment.com (based in Berlin) and indybay.org (based in San Francisco).

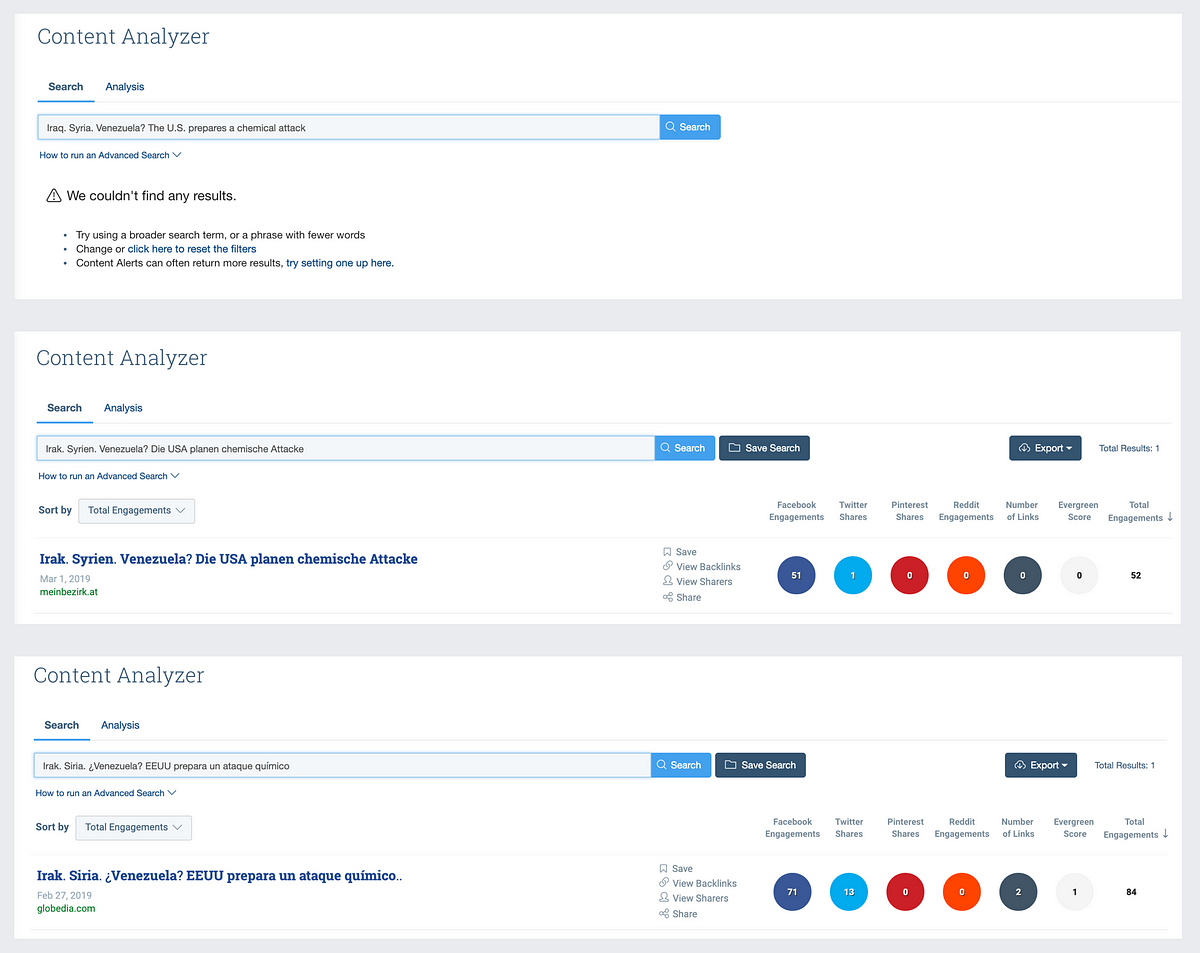

The operation posted articles in at least six languages, including English, German, Spanish, French, Russian, and Ukrainian. It also referenced documents in Arabic, Polish, and Swedish that it probably forged itself. The assets also posted articles about Armenia, Azerbaijan, the European Union, Germany, Ireland, Poland, Ukraine, the United States, and Venezuela.

The following graphic lists a selection of the platforms the operation is known to have used, and the languages deployed on each one.

The use of so many online forums indicates a key online vulnerability: the ease with which throwaway accounts can be created and used to post false content. It also underscores the size and scope of the operation: it would have taken significant resources to craft content in so many languages.

The Tradecraft

The operators used consistent tradecraft. They would create an account on an online platform and use it to post a false story, often incorporating forged documents. A second set of fake accounts would post expanded versions of the same story in multiple languages, using the original posts as their source.

In the third step, additional fake social media accounts amplified the false stories and tried to bring them to the attention of the mainstream media.

This approach resembled the conduct of Operation Infektion. The main difference between the two operations is that Operation Infektion focused on a single story, while New Infektion spread many stories.

High OPSEC

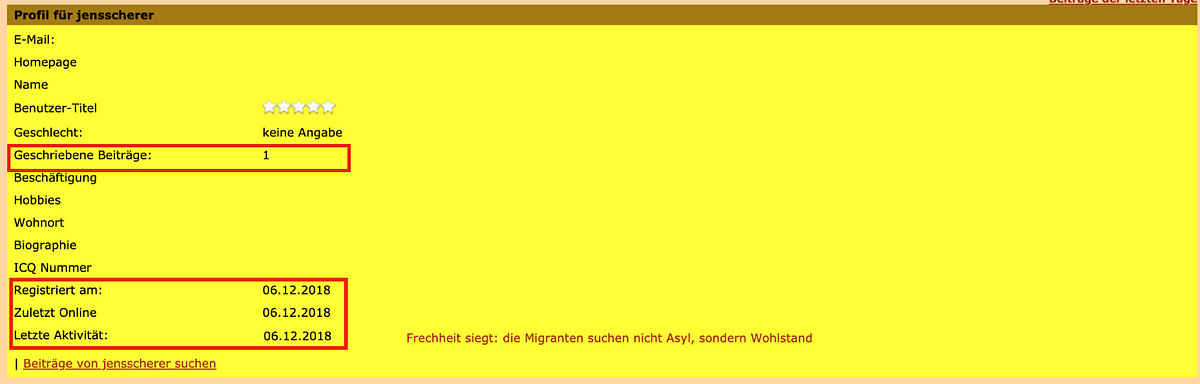

The operation stood out for its attention to operational security (OPSEC): efforts made to keep its activity covert. Most of its posts were made by accounts that were created the same day, posted the one article, and were never used again.

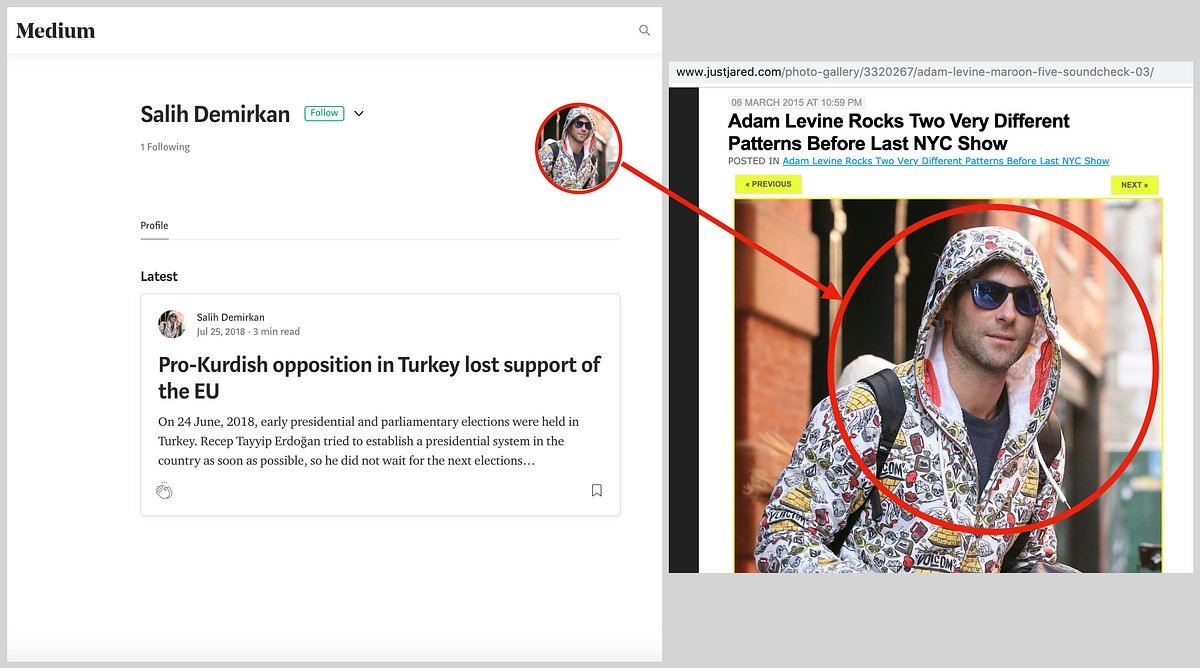

Many of the accounts did not even provide a profile picture, while a few took their images from online sources. This asset on Medium repurposed a photo of celebrity musician Adam Levine:

Paradoxically, this approach became one of the operation’s most common forensic clues. Repeatedly, the DFRLab’s investigation came across articles that, in addition to other clues, were posted by accounts that had been created the same day, used once, and abandoned.

This approach is suggestive of intelligence operators whose mission is to carry out their work undetected, without creating a discernible community; it is uncharacteristic of social media influencers and marketing experts, whose job is to garner as much attention for their work as possible and build as large a community as possible.

Impersonation and Infiltration

On several occasions, the operation impersonated real individuals who were politically active in their home countries. At least twice, the operation published screenshots of tweets that it attributed to leading political figures : then-Defense Secretary Gavin Williamson in the United Kingdom and Senator Marco Rubio in the United States. Open-source evidence indicated that both screenshots were photoshopped in an apparent attempt to stoke tensions between the United States and United Kingdom as well as within the United Kingdom.

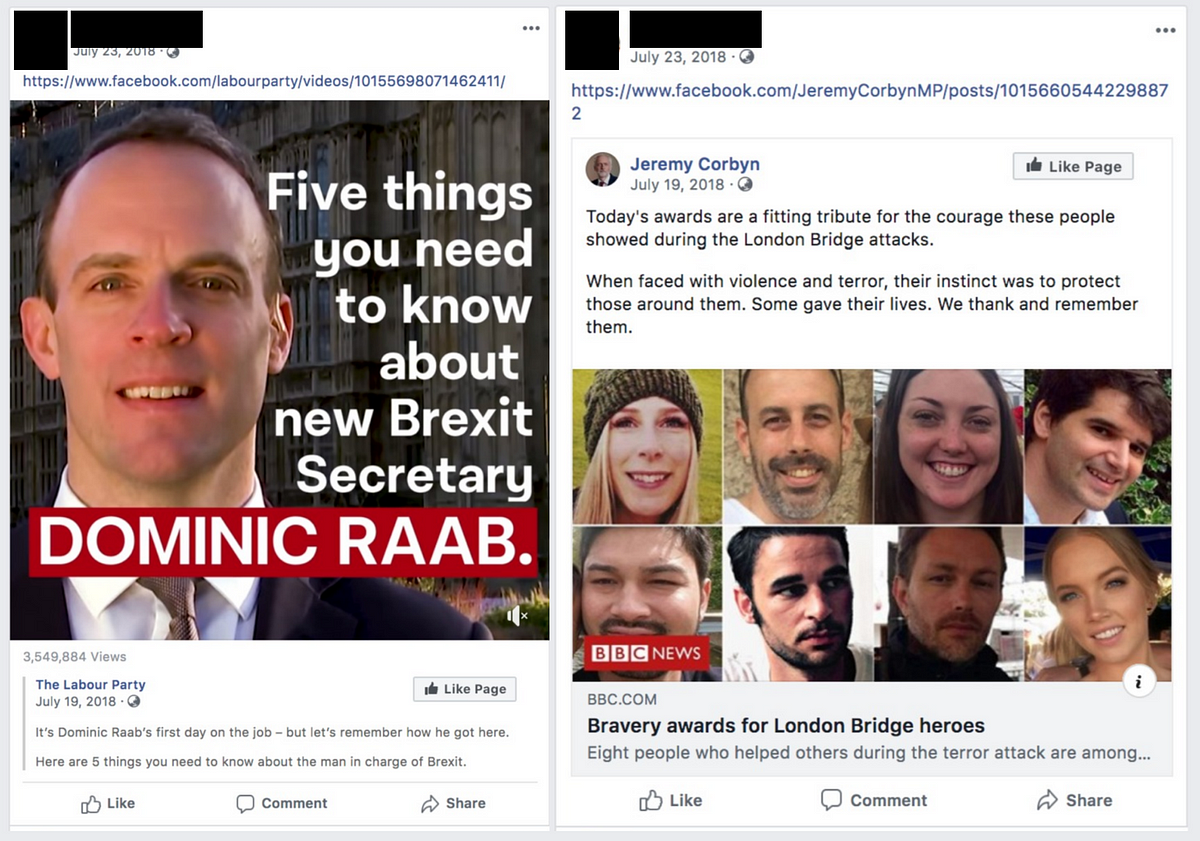

Meanwhile, two Facebook accounts impersonated citizens of the United Kingdom and one impersonated a citizen of another EU country. All were associated with parliamentary work.

In each case, the impersonation account copied its profile picture, banner, and “personal” posts (such as comments on sports and restaurants) from the real person’s profile. To protect the privacy of the real individuals involved, the DFRLab will not share any identifying details.

As an example of these operations’ tradecraft, however, one account posed as a person affiliated with the British Labour Party in Westminster. In between its “personal” posts, this account shared content from the Labour Party and its leader, Jeremy Corbyn. This appears to have been an attempt to establish a credible identity for the impersonation account.

Each of these impersonation accounts shared one story that the operation created. In each case, the story was based on a forgery, and the Facebook account was an early amplifier. Open-source evidence cannot determine whether the sole purpose of these unusually detailed fakes was to plant false stories or whether they were also intended to attract genuine followers for other purposes, such as entrapment or espionage.

High Drama, Low Impact

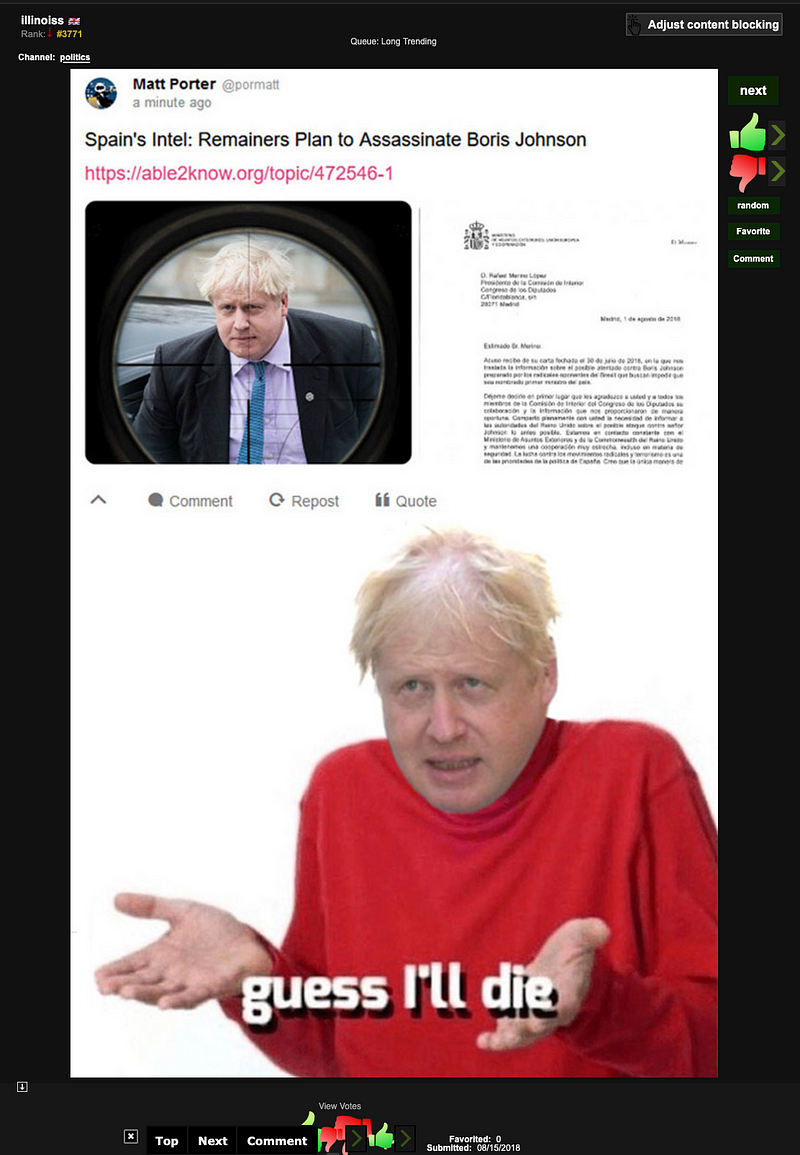

Many of the stories presented dramatic and emotional claims, apparently calculated to generate viral sentiment among conspiracy-minded communities. The most outstanding of these was an allegation in August 2018 that Spanish intelligence had uncovered a plot by opponents of Brexit to assassinate leading Brexiteer — now the favorite to become the United Kingdom’s next prime minister — Boris Johnson.

Despite such sensational content, or perhaps because of it, almost none of the operation’s stories had significant traction. This is likely in part due to the OPSEC measures that made it impossible for individual accounts to build a following.

The Facebook accounts seldom scored any reactions. Typical articles gathered a few dozen or a few hundred views, although some outliers recorded several thousands. Few comments were appended to any story, and those were usually negative.

The one exception was a virulently racist story the operation planted in German that was picked up by a local anti-immigrant news source. This outlet incorporated the fake content into a longer article that was shared over 3,500 times on social media.

Suspect: Russian Intelligence

Facebook attributed the operation to a “small network emanating from Russia.” The content supports that attribution: both the use of language and the choice of subjects were consistent with earlier known Russian operations.

The size of the network is a different question. In terms of the number of assets on Facebook, it was indeed small, but, in overall terms, it was on an industrial scale.

It operated across at least six languages (nine, if the forgeries are included), over 30 platforms, and dozens of fake accounts. It ran for several years, with some Russian-language content dating back to 2014. Its articles in different languages did not appear to be machine translated: they resembled works written by skilled, but nevertheless non-native language, human authors. This suggests a substantial operation with multiple language teams working simultaneously on content generation and translation.

The devotion to OPSEC was remarkable and sets this apart from any other operation the DFRLab has encountered. At the same time, the obsessive secrecy meant that almost all of the operation’s articles failed to penetrate. The use of Facebook accounts to impersonate politically active figures may also have had an intelligence role.

The operation originated in Russia. It was persistent, sophisticated, and well resourced. It prioritized OPSEC over clicks, showed a high degree of skill and consistency in its tradecraft, impersonated politically active European citizens, and often covered issues of direct relevance to Russian foreign policy.

Open sources cannot provide a definitive attribution, but on the basis of the evidence so far, the likelihood is that this operation was run by a Russian intelligence agency.

By @DFRLab

Ben Nimmo is Senior Fellow for Information Defense with the Digital Forensic Research Lab (@DFRLab) and is based in the United Kingdom.

Eto Buziashvili is a Research Assistant with @DFRLab and is based in Georgia.

Michael Sheldon is a Digital Forensic Research Associate with @DFRLab and is based in the United States.

Kanishk Karan is a Digital Forensic Research Associate with @DFRLab and is based in India.

Nika Aleksejeva is a Digital Forensic Research Associate with @DFRLab and is based in Latvia.

Luiza Bandeira is a Digital Forensic Research Assistant with @DFRLab and is based in Colombia.

Lukas Andriukaitis is a Digital Forensic Research Associate with @DFRLab.

Reema Hibrawi is an Associate Director at the Atlantic Council’s Rafik Hariri Center for the Middle East.

Follow along for more in-depth analysis from our #DigitalSherlocks.