By Urve Eslas, for CEPA

Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov, in a 17 February speech at the Munich Security Conference, described as “Russophobic” neighboring countries that oppose Russia’s core interests. The media’s use of this term has increased remarkably since Russia’s 2014 annexation of Crimea. The Kremlin’s weaponization of the word has also been applied in recent years to Estonia. Unfortunately Estonia itself seems to have adopted this label as well.

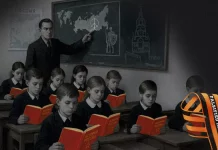

On 8 February, TVC—a Russian state-run TV broadcaster with the country’s fourth-largest coverage area—aired a talk show, Pravo Golosa [Right to speak/vote] that focused on the “Russophobic Baltic states.” Among other falsehoods, the program claimed that Estonia belongs to the “mental space” of the Russian Empire; that it is ruled by a U.S.-influenced regime; that it’s on the verge of economic and demographic collapse; that it supports Nazi movements; and that it discriminates against the Russian language and those who speak it. The show’s host presented the most significant narrative: that the Baltic states have signaled their desire to normalize relations with Russia, but that it’s questionable whether Russophobes can become Russia’s partners.

This narrative contains three misleading aspects: first, that the Baltic states want to normalize relations with Russia, as if the decision is up to them; second, that they have given signals confirming that intention; third, that the Baltics, including Estonia, are Russophobic; and fourth, that Russia may condition such normalization on the Baltics no longer being Russophobic.

First, Russia’s conflict with the West can never benefit its small neighbors. Unfortunately, lowering tensions does not depend on Estonia, on the other two Baltic states, or on the West in general. It depends on Russia. By organizing cyber attacks in Estonia in 2007, annexing Crimea in 2014, waging war in Ukraine and information war in the West, and using hacking, doxing, bots and dark ads to meddle in elections in the United States, France, Germany and elsewhere since 2016, Russia has changed the global security situation and the West has reacted accordingly. Nevertheless, Russia keeps presenting Western sanctions and additional NATO troops in the Baltics as proof that the West is the aggressor. The Kremlin has failed to see the West’s reaction as a result of its own deeds. It continuously uses the “blame the victim” technique and blames “Russophobic Balts” for turning the West against Russia.

Second, Estonian opinion leaders and decision-makers have indeed started to adopt these Kremlin narratives into Estonian public discourse. Most recently, Yana Toom — a member of the ruling Estonian Center Party (which has official ties with Russia’s ruling United Russia party) — stated in an article that since Estonia’s main priority is to ratify its border agreement with Russia, Estonia should change its Russian policy to “ease tensions” between two countries. This article was a reaction to Lavrov’s 15 January statement that in order to get the border agreement ratified, Estonia should stop its “Russophobic” behavior. In recent months, that narrative has found its way elsewhere into Estonian public discourse, Estonian media and political rhetoric through the use of the term Russophobic to describe Estonia’s policy, society and even identity. On 19 February, the chief editor of Estonia’s biggest daily newspaper, Postimees, described the tendency of adapting Kremlin narratives as a sign of growing “Russification.”

This can be seen from two perspectives. The first is the “gaslighting” technique CEPA has described elsewhere: repeatedly attempting to convince the other party that its memory, perception and everyday experience is false until it starts to believe the alternative version. It also is an example of interpellation—a phenomenon critical theorists have used to explain how ideas get into our heads and affect our lives, to the point that cultural ideas have such a hold on us we believe they are our own.

Imagine a man on the street suddenly hearing someone shout: “Stop the thief!” If that man has not stolen anything, he’ll probably just keep walking since he knows this was not meant for him. If the person has stolen something, he would probably look guilty or even start running. Yet if the man hasn’t stolen anything but acts as if he did, he accepts the “call” and becomes defined by it as a thief.

Similarly, Estonia—reacting to Russia’s narrative of it as a Russophobic country with guilt and acceptance—may become defined by it.Russia employs many narratives, but only those that Estonia responds to and adopts have the power to change its self-perception and eventually its policy. Unfortunately, the Kremlin’s narrative about Estonia as a Russophobic country seems to be the call Estonia has answered.

The Russian narrative on “Russophobic” countries has a long history that has been analyzed by CEPA and others. However, the Russian media’s use of the term has increased remarkably since the annexation of Crimea. Most recently, pro-Kremlin media outlets falsely portrayed recent talks on the future of Tallinn’s Soviet-era World War II monument, Maarjamäe, as a plan to demolish it, and as yet another sign of “Russophobic behavior.”

Fourth, Russia’s attempt to show that the normalization of its relations with Estonia— including ratification of the border agreement—depend on Estonia’s ending its Russophobic behavior should not be taken too seriously.

What should be taken seriously is Russia’s calculation that its relations with the West should improve, though on the Kremlin’s terms. The fact that the West has managed to stay more or less united against Moscow has caused more issues than Russia expected, including sanctions that have hampered economic growth. It should be clear that improved relations can be possible only when Russia stops waging war, both against Ukraine and in information and cyber space.

By Urve Eslas, for CEPA