By Janusz Bugajski, for CEPA

As the Russia-Ukraine war enters its fifth year, two recently published books illuminate the fundamental motives for Moscow’s ongoing offensive. They make a compelling case that the armed conflict is intended to demonstrate and perpetuate Russia’s dominance through the usurpation of Ukraine’s history, territory, and identity.

In a masterful dissection of Russian history (Lost Kingdom: The Quest for Empire and the Making of the Russian Nation, 2017) Harvard professor Serhii Plokhy focuses on the sources of identity adopted by Russia’s rulers since the Principality of Moscow launched its drive for territorial expansion in the 15th century.

Plokhy asserts that Russia’s “myth of origin” was the medieval state of Kyivan Rus—a multi-Slavic kingdom centered in modern-day Ukraine and established 200 years before Moscow appeared as a small town located in an outlying province. The Rus were a Norse tribe that founded the ruling Rurik dynasty in Kyiv, but the “Rus” name was subsequently appropriated by Moscow in one of the earliest recorded examples of identity theft. Muscovite rulers feigned descent from the Ruriks and claimed Kyiv as the birthplace of the Russian monarchy, state, and church. This fraudulent history became the legitimizing narrative for Russian tsars when the small autocratic Muscovite polity began its imperial adventure in the 15th century.

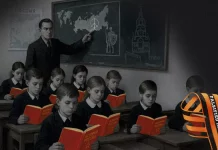

Moscow’s earliest propagandists depicted the three developing East Slavic nations (Belarusian, Russian, and Ukrainian) as “tribes” of one Russian nation. Moscow’s rulers consolidated their claims to dominate all Eastern Slavs by declaring Russia as the “Third Rome” or successor to Christian Byzantium, which was extinguished by the Muslim Turks in the 15th century. For the next 400 years, Muscovy annexed its neighbors’ territories and prevented the emergence of other East Slavic states. Its Russification campaign was crafted to eradicate the distinct identities and languages of neighboring Slavic peoples, particularly the Ukrainians, who had a more direct claim to Kyivan Rus.

Taras Kuzio (Putin’s War Against Ukraine: Revolution, Nationalism, and Crime, 2017), is a fellow at the Center for Transatlantic Relations at Johns Hopkins University. He provides a remarkably detailed assessment of the Kremlin’s current attempt to destroy Ukraine’s statehood. He contends that the root cause of the Russia-Ukraine war revolves around Moscow’s unwillingness to recognize Ukrainians as a distinct nation. For Moscow elites, Ukrainians and Belarusians are branches of a single Russian nation and their statehood cannot exist outside Russia’s “zone of privileged interests.”

The Kremlin cultivated President Viktor Yanukovych as a pro-Moscow satrap, and if not for the Euromaidan Revolution—which lasted from November 2013 to February 2014—his regime may have succeeded. Hence, the verbal venom in official attacks on an independent Ukraine, in which opponents of Russia’s overlordship are denounced as “fascists” and Western puppets. After seizing Crimea, Moscow manufactured a rebellion in Ukraine’s Donbas region to weaken Kyiv and convince international mediators to incorporate rebel held territories in a “federated” structure. The objective was to block Ukraine’s ambitions to join pan-European institutions and to revive Russia’s regional dominance.

Moscow continues to fuel the war in Donbas with weapons and fighters to consolidate the separatist strongholds and cripple the Ukrainian state. Since 2014, at least 30,000 people have perished in the conflict, about a third of them civilians, and millions have been displaced from their homes. Washington finally decided to provide Ukraine with defensive weapons, including anti-tank missiles, to help protect the country against Moscow’s assault. Given Russia’s history, the Kremlin is only likely to withdraw from Ukraine if it faces major resistance and substantial losses. Even then, the withdrawal could be temporary unless Ukraine builds up its military and eventually enters NATO to ensure its long-term security.

Paradoxically, Russia’s attack on Ukraine has had the reverse geopolitical effect of the one intended. It has significantly strengthened the determination of Ukrainians to resist Moscow’s political manipulation and military challenges. And above all, it has helped consolidate Ukrainian identity and statehood despite Russia’s historical and ideological deceptions.

Zbigniew Brzezinski famously asserted that Russia cannot simultaneously be an empire and a democracy, and if it seeks to control Ukraine it will remain an imperial state. For Russian ideologists, the existence of Ukraine negates the mythological constructs in Russia’s history, identity, and imperial statehood. Hence, the Kremlin not only seeks to obstruct Ukraine from joining Western institutions but it also saturates the information sphere with claims that Ukraine is an “artificial” country. At the core of this disinformation offensive is the fear among Kremlin officials that Ukraine will be perceived as a more legitimate state than Russia, both historically and currently.

Russia itself is approaching a crossroads. It can either evolve into a genuine federation or fracture into a dozen or more countries, as its diverse regions struggle for political and economic emancipation. And to be internationally respected and coexist with its neighbors, Moscow needs to disavow its imperial pretensions and historical inventions. To be authentic and durable, Russian identity cannot depend on the denial of Ukraine’s nationhood, statehood, or independence.

By Janusz Bugajski, for CEPA

Janusz Bugajski is a Senior Fellow at the Center for European Policy Analysis (CEPA) in Washington DC and host of the “New Bugajski Hour” television show broadcast in the Balkans.

Europe’s Edge is an online journal covering crucial topics in the transatlantic policy debate. All opinions are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the position or views of the institutions they represent or the Center for European Policy Analysis.