By Artem Zakharchenko 1,Tomáš Peráček 2,Solomiia Fedushko 3,*,Yuriy Syerov 3 and Olha Trach 3, for MDPI

1Institute of Journalism, Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv, 02000 Kyiv, Ukraine

2Department of Information Systems, Faculty of Management, Comenius University in Bratislava, 820 05 Bratislava, Slovakia

3Department of Social Communication and Information Activities, Institute of the Humanities and Social Sciences, Lviv Polytechnic National University, 79007 Lviv, Ukraine

*Author to whom correspondence should be addressed.

Sustainability2021, 13(2), 573; https://doi.org/10.3390/su13020573

Received: 15 December 2020 / Revised: 4 January 2021 / Accepted: 7 January 2021 / Published: 9 January 2021

(This article belongs to the Special Issue Entrepreneurship and Business Sustainability)

Abstract

Fact-checking and journalists professional standards usually are considered to be the best fail-safe against manipulations in media. However, we found that newsmakers are able to manipulate even the audience of so-called ‘high-quality media’ who practice all mentioned approaches. To prove this we have refined the concept of ‘pseudo-event’, introduced by D.J. Boorstin, by defining the term ‘fake newsworthy event’ as an event created by newsmakers, that is high-profile and attractive for media, but the only or particular aim of these actions is an agenda-setting, and this aim is not obvious from the origin of the action. Namely, the member of parliament may file some bill realizing that it cannot be adopted and trying just to shape the public opinion. Or some person may claim against a celebrity or businessman having no chance to win at trial. On the example of Ukrainian ‘high-quality media’ we showed that journalists usually do not take into account whether some topics are launched just for manipulating agenda-setting. To prove that we gathered the data about publications focused on such topics in Ukrainian ‘high-quality media’, we provided their discourse analysis, and compared the result with experts’ evaluations of ‘media quality’ and ‘artificiality rate’ of the topic. We have not found correlations between ‘artificiality’ of the topic and the number of publications. Recommendations were elaborated for the media workers if they want to avoid this type of manipulation.

Keywords: manipulations in media; fake news; agenda-setting; high-quality media; newsmakers; newsworthy events; Ukrainian media

1. Introduction

In the era of post-truth fact-checking is assumed as a reliable cure for media to remain truthful and maintain their proficiency. Keeping up the standards of accuracy, impartiality, diversity of views, also receive due attention of the scientists. In this study, which is focused on the interactions between newsmakers and media in Ukraine, we found that newsmakers are able to manipulate even the audience of so-called ‘high-quality media’ engaged in all these practices.This research focused on a special case of politicians’ manipulations in media named «pseudo-event». This concept was introduced by D. Boorstin in 1962 [1]. He defined it as ‘ambiguous truth that appeals to people’s desire to be informed’. We focused on some particular type of pseudo-events that may be named a fake newsworthy event or a fake peg. The intention is to separate cases when newsmakers take some actions that are high-profile and attractive for the media, but the only or particularly aim of these actions is agenda-setting of first, second, or third level (see below in the section ‘Agenda setting and manipulations’), and this aim is not obvious from the origin of the action.Researchers and media literacy teachers usually do not consider manipulations with agenda. It is assumed that agenda-setting is undisguised, and therefore a ‘legitimate’ influence. Therefore, fake newsworthy events are intrinsically manipulative agenda-setting actions. For example, when the member of parliament files a bill realizing that it cannot be adopted and aiming only at making an impact on public opinion. Or, when a person claims against a politician or celebrity having no chance to win at trial.This paper aims to reveal, whether the newsmakers are able to manipulate high-quality Ukrainian media by making fake newsworthy events, and whether these media have a tool to avoid this type of manipulation?Using the material from Ukraine, this article demonstrates that journalists of even ‘high-quality’ Ukrainian media usually do not reflect on the objectives of newsmakers and cannot identify the manipulations with the agenda. In cases like mentioned above, they typically provide fact-checking and the balance of opinions, even though any publication including critical to the newsmaker can have an impact on the agenda.

2. Theory and Background of Research

Agenda-setting and manipulations. In this article, by manipulations, we understand hidden intentional influence that the recipient (be it a journalist or a reader of a news article) usually cannot recognise. From this perspective, for example, value judgments made by politicians in speeches during political campaigning are not manipulation per se, as they are not hidden. The same applies to the bias of partisan media unless it is not concealed.Media watchdogs consider manipulation as a common activity of politicians, other newsmakers, biased media and social media [2]. Ukrainian government even wants to define clearly this term and make it an offense [3]. This is not only a Ukrainian phenomenon, Natalia Roudakova proved that Russian media discourse is manipulative to a great extent, and it is based on media corruption [4]. Wherein common is the situation when communicators, specifically propagandists, newsmakers, PR-managers, have some hidden goals. The legal context [5,6] in the digital society [7] and branding strategy for small and medium enterprises [7,8,9,10,11] is the subject of investigations of many scientists.Journalists usually concern of the simplest and yet very powerful type of manipulations: it is ‘fake news’ as an intentional distortion of facts [12]. Its efficiency rests on the audience’s media ignorance and their unaccustomance to fact-checking. Thus, researchers have demonstrated that people inclined to consume and sharing tabloid content are more likely to share fake news [13]. Scientists rediscovered media ignorance of western countries’ inhabitants after the 2016 American presidential elections and Brexit referendum. Since then, numerous publications have been focused on this problem [14,15], and found that elder people and conservative supporters in the United States and Great Britain were more active in fake news sharing, and people who saw one fake message were likely to view multiple [16]. Definitions and typology of disinformation, misinformation and fake news was thoroughly reviewed by the European Commission [17] as well as by several other researchers [18,19,20].Similarly, Ukraine faced a significant—in its extent and, arguably, consequences—uptake in fake news in late 2013, during the Revolution of Dignity and the subsequent war in the East of the country [21].Since 2016, scientific and media discourse focused on fact-checking, in particular, due to the Facebook and Twitter efforts of combating fake news [22]. Therefore, there were some opinions that this excessive focus is not beneficial for the society [23]. Media relies on fact-checking to control for false statements. However, we need to recognise that other types of influence do not necessarily imply false statements. For example, manipulations with agenda-setting. Political scientists revealed several types of fraud in this field.Researchers distinguish three levels of agenda-setting. The first level is aimed at the idea that the frequency with which media mention issues or public persons defines what objects people consider to be important for the society [24]. So, the media set the public salience for these objects. The second level deals with the attributes of objects: mentioned repeatedly with some ‘labels’, issues or public figures are remembered by the audience in the proper context [25]. Meanwhile, proved, that the second level is crucial for the little-known persons whose public image has not constituted yet, and negative attributes affect the attitude to objects much more than positive [26]. Finally, the third level shows how media establishes connections between objects in some cognitive network-like structure [27]. So, the media may not only define ‘what we have to think about’ and ‘how we have to think about it’, but they can also define ‘what and how we have to associate’ [28].All these levels could be manipulated. The first known type of manipulative agenda-setting is based on fake news agenda-setting power [29]. Even when the fake origin of some message is obvious, the object of news, its attribute, or its connection to the other objects eventually could become more salient.The second type of manipulations results from agenda-ownership theory, which argues that known political parties or candidates ‘own’ some issues of public concern. So, boosting media salience of such an issue allows increasing the support of its owner [30]. Brandenburg and Heinz highlight a specific type of media bias: agenda bias, i.e., frequent mentions of issues owned by some candidates, along with coverage bias (frequent quotation of the candidate) and statement bias (disproportionate positive or negative coverage of candidate) [31]. As we noted above, undisguised bias is not a manipulation, nevertheless, hidden statement bias undoubtedly is.At last, the third type of manipulative agenda-setting is ‘pseudo-events’ [1]. Boorstin did not focus on the agenda-setting at least because this concept was not introduced at the time. He paid attention that pseudo-events are usually pre-scheduled and advertised by media so people believe in their importance on the contrast of spontaneous events. Therefore, other researchers defended prepared events and gave examples of pre-announced events that were essential for the readers [32]. On the other hand, public relations specialists also separate pseudo-events from more effective ‘legitimate events’ that allow direct communication between the company and the public [33].So, to avoid confusion in this article the term ‘fake newsworthy event’ will be used instead of ‘pseudo-event’ to describe the events that are not only prepared but also have no other goal besides the agenda-setting. In other words, it is assumed that there are some newsworthy events made by newsmakers for some declared reasons, but their real aims do not coincide with the declared ones. Usually, the real aims of communicators remain unknown. Therefore, some cases became public because of the hackers who reveal their letters. A good example is a publication of the correspondence of pro-Kremlin propagandist Iskander Hisamov by hacker community ‘MadUkrop$_Crew’ in February 2017 [34]. This correspondence reveals the real aims of several information campaigns made by Russian propaganda in Ukraine in 2009–2017.It is understandable, that when a politician starts to speak about some political issue and make it more salient; when activists make a protest or public person goes on a hunger strike to draw attention to public concern; when somebody writes a book about a problem, all these activities are undisguised in their desire to shape the public agenda. But that is a different story when we have an action with a stated goal that is not to set the agenda, but in fact, this is the only aim. Also, manipulative topics started to divert attention from other issues which are more valuable for the society.Ukraine’s media landscape. The discourse of media manipulations is very advanced in the Ukrainian information space. This situation roots in the informal influence of politicians on media, which is typical in hybrid political regimes and includes clientelism, patronage, rent-seeking [35], self-censorship [36], etc. Therefore, the Ukrainian media system fits into the framework of the Polarized Pluralist model [37] according to the classification by Hallin and Mancini [38]. It has no influential party press which is more common in the Democratic Corporatist model. Therefore, this influence is hidden and strong. Knowing that the Ukrainian audience has a low level of confidence in media—about 31% [39]. Sociologists working in the post-Soviet region have long noted that soon after the fall of the USSR, with the emergence of privately owned media, news audiences developed a heuristic of correcting for the ownership of news outlets [40,41]. This suggests they expected the news to reflect the interests of media owners. It seems that the discourse of ‘media manipulation’, which some note in Ukraine (e.g., [42]), is connected to these structural conditions.Ukrainian media system after the Revolution of Dignity (2013–2014) received a boost towards a democratic model, writes D. Orlova: ‘Some crucial reforms recently launched like the establishment of public broadcasting and privatisation of state and communal media have a substantial potential for democratisation of the Ukrainian media system… indicate the media and journalists’ quest for independence’ [43,44]. Therefore, she notices complex challenges that Ukrainian Journalism faces: oligarchs’ control over the major media became an instrument in achieving their political goals; the economic crisis and a substantial decline in the advertising market; unfinished public broadcasting reform; and, finally, the problem of personal journalists security under the circumstances of the Ukrainian-Russian war. An additional problem is the low ethical level of many Ukrainian media workers and, as a result, the widespread of hidden ads [45]. But Ukrainian media is not the only news source for Ukraine. Russian media content poisoned by propaganda is still available for Ukrainian consumers in spite of legal restrictions of their broadcasting [46]. J. Szostek showed that consuming the content of Russian media is the best predictor of Russian narrative support, much stronger than communications with Russian relatives, living in Russia in the past, etc. [47].On the other side, social media in Ukraine also have a strong political impact. The self-organised communities evolved in 2013–2014 to succeed in countering Russian fakes [48], in meme war with Russian trolls [49], social media activists became influential in the public sphere [50]. This uprise of social network communication activity in the following years formed the strong core of patriotic activists mainly loyal to the former president Petro Poroshenko, while his main competitor in the recent elections, Volodymyr Zelenskyi, targeted the periphery of social network users [51,52].Under such circumstances, it is too hard for the majority of the media to remain unbiased and maintain a high professional level. Therefore, the Ukrainian NGO ‘Institute of Mass Information’ regularly promulgates the ranking of online media in terms of compliance with journalistic standards of credibility, the balance of thoughts and separation of facts from comments [53].Top positions there get media of various funding models, in particular, state media (Ukrinform), commercial (Ukrainska Pravda and Dzerkalo Tyzhnya), donated from business depended on this media brand (Liga and Ukrainskyi Tyzhden).A backdrop for all these processes is a disquieting situation in Ukrainian political life. In the 2019 presidential elections, former comedian Volodymyr Zelenskyi won with 73% support, using a unique non-agenda ownership strategy [54]. Now his struggle with different parts of the old political elite continues. His main opponent is still an incumbent Petro Poroshenko who utilises the patriotic agenda. Also, he confronts Yulia Tymoshenko with social agenda and party ‘Opposition Platform for Life’ with the pro-Russian agenda. This struggle lasts on different battlefields including parliament, ministries and, of course, media and social media [51].

3. Materials and Methods

Hypotheses. Based on the above, this paper aims to reveal whether the newsmakers are able to manipulate high-quality Ukrainian media by making fake newsworthy events and whether these media have a tool to avoid this type of manipulation?This allows us to postulate two hypotheses:Hypotheses 1 (H1).Newsmakers using fake newsworthy events successfully boost their manipulative topics even into the ‘high-quality media’, and the salience of these topics doesn’t correlate with the indicators of media quality and the artificiality rate of the topic, evaluated by the experts.Hypotheses 2 (H2).Other newsmakers may confront the proliferation of topics based on fake newsworthy events by launching their own newsworthy events.It was assumed that the number of publications which mention a certain topic depends on at least three parameters: First, how many newsworthy events appeared in this topic; second, how significant are the actors of the topic to this media; and third, how significant changes occur with these actors.Apparently, when a journalist feels that the aim of the topic starter is phony, and his or her main goal is the public opinion influence, it should decrease the third parameter.Research design. The general pattern of the research was as follows:

- Single out topics that were mentioned in the media as probably started for the agenda manipulations and evaluate their ‘artificiality rate’ by the expert survey.

- Single out Ukrainian high-quality media and evaluate their ‘quality’ by the expert survey.

- Count publications that each media has dedicated to each topic.

- Count the average number of publications that each media published while covering topics like these.

- Provide a discourse-analysis of all these publications to indicate specific categories and calculate their number.

- Establish a correlation between all these indicators.

So, in broad strokes, the research rests on the comparison of two types of indicators. The first type is measured parameters, and the second—evaluated by experts.The expert survey was conducted in October 2019 and covered 7 professionals well-versed in the current communication situation in Ukraine. This number includes one PR-manager, one media manager, one political analyst, one fact-checker, one media editor and two media analysts. All respondents work with Ukrainian communication campaigns and know well the newsmakers’ decision-making process.Everyone has at least 10 years of experience in this area including leadership in nationwide communication projects. So, they can judge their goals. They had never worked with each other in the same organisation, so, their thoughts are quite independent.The list of topics was composed of those evolved in media space in January–October 2019, were started by real, intentional, non-spontaneous actions and were mentioned in Ukrainian media as ‘launched just for PR reason’ or ‘to divert attention’. In doing so, topics that were started with actions that are undisguised in their desire to shape the public agenda, including protests, hunger strikes and so on, were excluded.The final list of selected topics is indicated in Table 1.Table 1. Topics selected for analysis.

Our sample of media whose ‘quality’ was evaluated by experts is based on the Institute of Mass Information ranking, complemented by adding several media with western funding (BBC Ukraine, Deutsche Welle, Radio Liberty). We meant by the ‘quality’ not only compliance with journalistic standards, so we used in our expert survey the following question: ‘To what extent this media corresponds to the term “high-quality media” (provides balanced, impartial and complete information, first of all, covering topics vital to the society, does not fall under any significant external influence on the editorial policy)’. Experts were asked to assess the Rm indicator by estimating the quality of media from the sample on a scale of 1 (Sure it is not a ‘high-quality media’) to 5 (It completely corresponds to ‘high-quality media’). The final list of media and their assessments is presented in Table 2, in the two first columns.Table 2. The features of the media’s coverage of investigated topics.

All topics were evaluated by experts from 1 (The only aim of starting the topic is influencing the public agenda) to 5 (topic was not started for influencing the public agenda at all), it is the Rt indicator.It can be seen that experts often make claims that some topics were started ‘just for PR reasons’, and these claims by itself may be used by communicators as messages of PR campaigning, regardless of whether this claim is true or false. That is why it was necessary to make an expert survey. Participating in it, experts understood that their answers will not be used in the media space, so they did not have any reason to lie.Then the Ukrainian media monitoring system Mediateka was used to count the number of publications on each topic for each media under research. This system provides full-text search of media publications including Ukrainian online news websites, printed press and news outlets on TV and radio, so it covers all types of media we have in the sample.Then we provided the discourse analysis of this set of publications. They were divided into three categories.The first one includes regular mentions of a topic, both positive and negative to the topic starter, because both increase the salience of objects, attributes, or connections between them. For example, these first type mentions of the first topic, ‘Civil actions against Petro Poroshenko, filed by Andrii Portnov’, included publications negative to Poroshenko (i.e., with the heading ‘Portnov claims that he is taking a lawsuit against Poroshenko into State investigating bureau’) as well as positive to him (‘Poroshenko named Portnov’s claims political persecution’). Both publications help establish connection ‘Poroshenko–criminal’, despite of their different sentiment. Two indicators are introduced: N1m—the number of this type of mention of all investigated topics in some particular media, and N1t—the number of this type of mention of some particular topic in all investigated media.The second category includes publications with mentions of topics and with a statement that this topic is launched for ‘PR reason’ or for ‘agenda-setting reason’, that its aim is phony, and the main goal is the public opinion influence. This statement could be a part of the speaker’s quote or the editorial text. For example, in the first topic, the mentions of the second type include the publication with the heading ‘Poroshenko believes that Portnov’s civil actions are just a part of the parliamentary campaign’. This publication devalues agenda setting effect of previous publications on the topic. The numbers of such publications are named N2m and N2t for each media and each topic respectively.The third type of publication was identified only in two investigated topics. Therein the topic starter’s adversaries not just criticised him, but also took asymmetric actions to destroy his aims. Namely, the Ukrainian delegation to the UN used a discussion about Ukrainian language law instigated by Russia to actualise the issue of Ukrainian sailors imprisoned by Russia. This led to headers like: ‘On the session of the UN Security Councile convened by Russia EU countries made reference to the prisoned Ukrainian sailors’. Likewise, Poroshenko’s lawyers filed a counterclaim against Portnov that his crime report is known to be falsified. The headings were: ‘Case file was opened on Portnov concerning its false testimony’. The number of these third type publications was marked N3m and N3t for each media and each topic respectively.Finally, to take into account other parameters affecting the number of publications apart from the Rm and Rt indicators, a comparative sample of topics was created. Given that different media publish a different number of publications per day and pay different attention to different topics. Seven topics were selected, which exactly were not launched for the agenda-setting reasons and which have the same actors as the main investigated topics. For example, comparative topic about Andrii Portnov—it was students protests against his appointment as a professor of Kyiv University, and for SkyUp airlines—launch of domestic flights of this company. Based on these topics, the average attention of each investigated media to this kind of topic was calculated, it is an indicator Cm—the number of publications dedicated to the topics of the comparative sample. That allows calculating how much more or how much less than usually certain media paid attention to the investigated topics: it is the expression N1m/(Cm*∑N1m).Also, the number of newsworthy events (initial action and further statements and comments of speakers, responsive actions, etc., except asymmetric actions described above) in each investigated topic was calculated. For example, in the case of the bill filled by Bohomolets, there were five newsworthy events: the bill filling itself, Bohomolets’s statement for press, comment of Health minister Ulyana Suprun on the topic, comment of the ‘Holos’ party leader Sviatoslav Vakarchuk on the topic and, at last, parliament’s return of the bill for improvement. This number is an indicator I. That allows calculating the average attention to each newsworthy event of a certain topic: it is the expression N1t/I.

4. Results

All indicators described above are shown in Table 2 and Table 3. Also, an interesting qualitative result was received. In the beginning, the share of journalists and news editors in the expert sample was supposed to be more. But many journalists refused to give answers after reading the questions. They claimed that they could not speculate on the newsmakers’ motivation. In other words, many media workers do not set out to ask themselves such questions.Table 3. The features of the coverage of the topics by the investigated media.

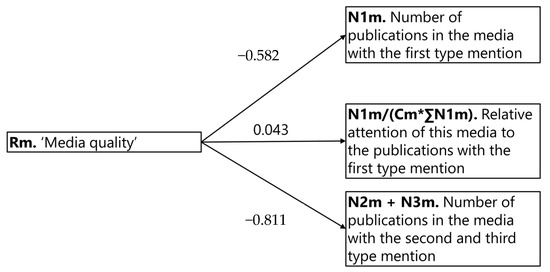

Analysis of the data demonstrates that H1 is true. Namely, the correlation between the ‘Media quality’ (Rm) and the relative attention of media to the publications with the first type mentions (N1m/(Cm*∑N1m)) is insignificant (0.043).Seemingly, in Figure 1, increasing the ‘Media quality’ leads to decreasing the number of publications with the first type mentions (correlation of −0.582). But the number of publications with the second and third type mentions decreases even faster (−0.811).

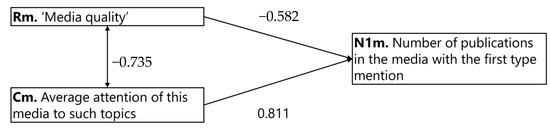

Figure 1. Correlations of ‘quality’ of the media and features of their coverage of investigated topics.Considerable consistency of Rm and N1m can be attributed to the fact that in our sample media of ‘higher quality’ publish on average less news than ‘lower quality’, this applies to any publications, not only those with the first type mentions (see Figure 2). Indeed, there is an inverse correlation (−0.735) between Rm and the average attention of some particular media to such topics (Cm).

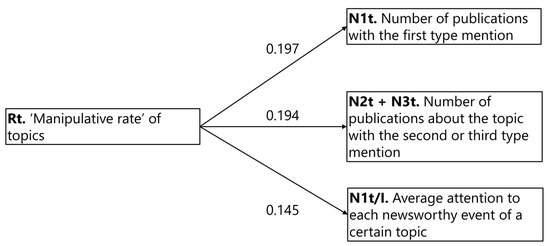

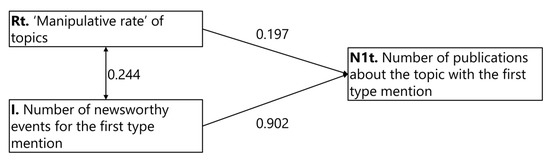

Figure 2. Correlations of a number of publications with the first type mention, ‘quality’ of the media and their average attention to such topics.Similar findings can be made from the evaluation of the topic. In Figure 3 correlations of ‘Manipulative rate’ of topics (Rt) with the number of publications with the first type mentions (N1t) and the second and third type (N2t + N3t) are almost identical and very weak (0.197 and 0.194 respectively). Rt correlation with average attention to each newsworthy event of some particular topic (N1/I) is even weaker (0.145).

Figure 3. Correlation of a ‘manipulative rate’ of topics and features of their coverage by investigated media.Figure 4 shows that the N1t is determined much more by the number of newsworthy events (I, correlation of 0.902) than by the ‘manipulative rate’ of the topic (Rt, correlation of 0.197).

Figure 4. Correlation of a number of publications with the first type mention in a topic, its ‘manipulative rate’, and the number of newsworthy events.It was additionally tested whether correlations are stronger in two circumstances: (a) if taken into account only the media of the ‘highest quality’, with Rm ≥ 4, and (b) if taken into account only the topics with the highest ‘manipulative rate’, Rt ≤ 2. Both calculations gave the findings with almost the same correlations as in the main dataset.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

The confirmation of H1 means that in a case when a newsmaker who is newsworthy enough by himself makes an action, he just needs to create as many pegs as possible, for example, incite answers of his opponents, and he will influence the agenda even of the ‘high-quality media’. This works even in the case of fake newsworthy events starting a topic. Because it seems that at least Ukrainian media workers usually do not take care whether some topics may be started just for the agenda-setting, and communication experts may prove that, or not.On the other hand, when some of the speakers quoted by the media argue that this topic is unworthy and launched ‘just for PR reason’ or ‘just for agenda-setting’, this statement usually spreads well. As well, as the counterattacks: asymmetric actions of opponents also aimed to reshape the agenda. Because N2t/I, as well as N3t/I, exceed N1t/I for most of the topics.Nevertheless, at least in the investigated cases, so-called ‘high-quality media’ do not repeat these statements about the ‘PR nature of topics’ in the backgrounds of the next publications, that are written on the occasion of the next pegs. It may be shown in the example of Andrii Portnov’s civil actions against Petro Poroshenko. A week after filing his first lawsuit, the lawyers of the former president named this civil action ‘a legal trolling’, and then filled a counterclaim that his crime report is known to be falsified. ‘High-quality media’ paid serious attention to both pegs. But then these messages were almost never used in the backgrounds of the news about further Portnov’s lawsuits. This proves, that statements about the ‘PR nature’ of topics are spread by media as ordinary political claims, and usually not taken into account as a real expert conclusion that should impact the topic salience in media.So, H2 is confirmed partially: other newsmakers may actually launch their own newsworthy events and probably get a decent number of publications. But this outcome may be short-lived, at least if the asymmetric answer is not so newsworthy as an initial start of a topic. By all means, this tactic is better than just a criticism of the initial newsworthy event: this criticism just helps the topic starter to set his agenda.The fake newsworthy events manipulation is a good example of the undesirable influence of newsmakers that can be spread even through the so-called ‘high-quality media’. As shown in this paper, this manipulation may be very powerful and result in significant social and political changes. So, the media should have an instrument to avoid an undesirable influence on their agenda. To resist this influence, media may rely not only on the fact-checking and BBC standards but also reflect on the newsmakers’ motivation for starting the topics. Instead, news editors usually do not see it as a problem and ignore the agenda-setting consequences of their work. There may be two explanations. The first one is the lack of news editors’ understanding of agenda setting influence of their media. They may focus on ‘just informing people’ and do not recognise a transparent agenda-setting as indicator of their ‘quality’. The second one is that journalists ignore agenda-setting consequences of the news because of high visibility of such news and audience attraction. They can’t afford to publish fake news for this reason, consider themselves ‘high quality media’, but they do not hesitate to do this with agenda-setting manipulations.In further research it would be useful to explore the overall attitude of journalists to their agenda-setting function to determine whether the case of fake newsworthy events is just a particular example or there is systematic ignorance of media workers in the agenda setting field.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, A.Z., S.F. and Y.S.; methodology, A.Z.; validation, A.Z.; formal analysis, A.Z.; investigation, A.Z.; resources, A.Z., S.F., Y.S. and O.T.; data curation, A.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, A.Z., S.F., Y.S., and O.T.; writing—review and editing, A.Z., Y.S., and S.F.; supervision, T.P.; visualisation, S.F., O.T. and Y.S.; project administration, S.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by National Research Foundation of Ukraine within the project ‘Science for the safety of human and society’, grant number 94/01-2020 ‘Methods of managing the web community in terms of psychological, social and economic influences on society during the COVID-19 pandemic’ and the Slovak Research and Development Agency under the contract No. APVV-19-0581 and by of the Faculty of Management of Comenius University in Bratislava, Slovak Republic.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We would like to offer our special thanks to the head of the Institute of Journalism of Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv Volodymyr Risun, as well to Victoria Shevchenko, the head of the Multimedia Technology and Media Design Department, for the organizational support in getting these results. The same applies to the staff of the Center for Content analysis, which was the base for this analysis. Assistance provided by the head of this company Elizaveta Morozova was greatly appreciated. We would also like to thank all experts who participated in the survey determined the ‘media quality’ and ‘Topic manipulative ranking’. This article is possible because of all this support. Ours special thanks are extended to Taras Fedirko for the fruitful discussion about this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Boorstin, D. The Image: A Guide to Pseudo-Events in America; Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group: New York, NY, USA, 2012; Political Science; p. 336. [Google Scholar]

- TOP-20 Publications about Media Manipulations in 2019. Media Sapience. Available online: https://ms.detector.media/manipulyatsii/post/24001/2019-12-30-top-20-materialiv-pro-mediini-manipulyatsii-u-2019-rotsi-dubinskii-sharii-chornukha-i-boti/ (accessed on 30 December 2019).

- Ministry under Borodyansky Works out Criteria of Manipulation in Journalism. Institute of Mass Information. Available online: https://imi.org.ua/en/news/ministry-under-borodyansky-works-out-criteria-of-manipulation-in-journalism-i30428 (accessed on 13 November 2019).

- Roudakova, N. Losing Pravda; Losing Pravda: Cambridge, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seilerová, M. The Consequences of Psychosocial Risks in the Workplace in Legal Context. Central Eur. J. Labour Law Pers. Manag. 2019, 2, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okanazu, O.; Madu, M.; Igboke, S. A recipe for efficient and corrupt-free public sector. Central Eur. J. Labour Law Pers. Manag. 2019, 2, 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svec, M.; Olsovska, A.; Mura, L. Protection of an “Average Consumer” in the Digital Society-European Context. In Proceedings of the International Scientific Conference on Marketing Identity, Smolenice, Slovak Republic, 7–8 November 2017; Marketing Identity: Digital Life, Pt II. Book Series: Marketing Identity; 2015. pp. 273–282, ISBN 978-80-8105-780-9. [Google Scholar]

- Halasi, D.; Schwarcz, P.; Mura, L.; Roháčiková, O. The impact of eu support resources on business success of family-owned businesses. Potravinarstvo Slovak J. Food Sci. 2019, 13, 846–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korauš, A.; Kaščáková, Z.; Felcan, M. The impact of ability-enhancing HRM practices on perceived individual performance in IT industry in Slovakia. Central Eur. J. Labour Law Pers. Manag. 2020, 3, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musová, Z. Responsible behavior of businesses and its impact on consumer behavior. Acta Oeconomica Universitatis Selye 2015, 4, 138–147. [Google Scholar]

- Graa, A.; Abdelhak, S. A review of branding strategy for small and medium enterprises. Acta Oeconomica Universitatis Selye 2016, 5, 67–72. [Google Scholar]

- Tandoc, E.C.; Lim, Z.W.; Ling, R. Defining ‘Fake News’: A Typology of Scholarly Definitions. Digit. J. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadwick, A.; Vaccari, C.; O’Loughlin, B. Do Tabloids Poison the Well of Social Media? Explaining Democratically Dysfunctional News Sharing. New Media Soc. 2018, 20, 4255–4274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allcott, H.; Gentzkow, M. Social Media and Fake News in the 2016 Election. J. Econ. Perspect. 2017, 31, 211–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guess, A.; Nagler, J.; Tucker, J.A. Less than you think: Prevalence and predictors of fake news dissemination on Facebook. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaau4586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grinberg, N.; Joseph, K.; Friedland, L.; Swire-Thompson, B.; Lazer, D. Fake news on Twitter during the 2016 U.S. presidential election. Science 2019, 363, 374–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Comission. A Multi-Dimensional Approach to Disinformation; TNS Political & Social European Commission: Luxembourg, 2018; Volume 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, B.; Hoang, D.T.; Nguyen, N.T.; Hwang, D. Fake News Types and Detection Models on Social Media A State-of-the-Art Survey. In Proceedings of the Intelligent Information and Database Systems, 12th Asian Conference, Phuket, Thailand, 23–26 March 2020; ACIIDS 2020. pp. 562–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maria, M.; Sundar, S.; Le, T.; Lee, D. ‘Fake News’ Is Not Simply False Information: A Concept Explication and Taxonomy of Online Content. Am. Behav. Sci. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazer, D.; Baum, M.A.; Benkler, Y.; Berinsky, A.J.; Greenhill, K.M.; Menczer, F.; Metzger, M.J.; Nyhan, B.; Pennycook, G.; Rothschild, D.; et al. The science of fake news. Science 2018, 359, 1094–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Göran, B.; Jordan, P.; Ståhlberg, P. From Nation Branding to Information Warfare: Management of Information in the Ukraine-Russia Conflict. In Media and the Ukraine Crisis: Hybrid Media Practices and Narratives of Conflict; Peter Lang: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt, A.; Gentzkow, M.; Yu, C. Trends in the Diffusion of Misinformation on Social Media. Res. Politics 2019, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasodomski-Jones, A.; Smith, J.; Jones, E.; Judson, E.; Miller, C. Warring Songs: Information Operations in the Digital Age; London, UK, 2019. Available online: https://demos.co.uk/project/warring-songs-information-operations-in-the-digital-age/ (accessed on 17 May 2019).

- McCombs, M.E.; Shaw, D.L. The Agenda-Setting Function of Mass Media. In The Public Opinion Quarterly; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1972; Volume 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCombs, M. New Frontiers in Agenda Setting: Agendas of Attributes and Frames. Mass Commun. Rev. 1997, 24, 32–52. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H.D.; Coleman, R. Advancing Agenda-Setting Theory: The Comparative Strength and New Contingent Conditions of the Two Levels of Agenda-Setting Effects. J. Mass Commun. Q. 2009, 86, 775–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Vu, H.T.; McCombs, M. An Expanded Perspective on Agenda-Setting Effects. Exploring the Third Level of Agenda Setting Una Extensión de La Perspectiva de Los Efectos de La Agenda Setting. Explorando El Tercer Nivel de La Agenda Setting. Rev. Comun. 2012, 11, 51–68. [Google Scholar]

- Vu, H.T.; Guo, L.; McCombs, M.E. Exploring “the World Outside and the Pictures in Our Heads”. J. Mass Commun. Q. 2014, 91, 669–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargo, C.J.; Guo, L.; A Amazeen, M. The agenda-setting power of fake news: A big data analysis of the online media landscape from 2014 to 2016. New Media Soc. 2017, 20, 2028–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bélanger, É.; Meguid, B.M. Issue Salience, Issue Ownership, and Issue-Based Vote Choice. Elect. Stud. 2008, 27, 477–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandenburg, H. Political Bias in the Irish Media: A Quantitative Study of Campaign Coverage during the 2002 General Election. Ir. Political Stud. 2005, 20, 297–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, E. Daniel Dayan, and Pierre Motyl. Communications in the 21st Century: In Defense of Media Events. Organ. Dyn. 1981, 10, 68–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallahan, K. Strategic Media Planning: Towards an Integral Public Relations Media Model; Public Relations; Heath, R.L., Ed.; Sage: HeathThousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2001; pp. 461–470. [Google Scholar]

- Media Iscanders Don’t Laugh: «Vesti», «UBR», «Strana.UA» and «Ukraina.RU» as the Moscow Lobby. InformNapalm. Available online: https://informnapalm.org/ua/media-iskandery/ (accessed on 12 February 2017).

- Ryabinska, N. Ukraine’s Post-Communist Mass Media: Between Capture and Commercialization; ibidem: Hannover, Germany, 2017; p. 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedirko, T. Liberalism in fragments: Oligarchy and the liberal subject in Ukrainian news journalism. Soc. Anthropol. (under review).

- Voltmer, K. How Far Can Media Systems Travel? Comparing Media Systems Beyond the Western World; Hallin and Paolo Mancini; Daniel, C., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2012; pp. 224–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallin, D.; Mancini, P. Comparing Media Systems; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ukrainians Most of All Trust Ordinary People, Volunteers, Churches and Army. Kyiv Post. Available online: https://www.kyivpost.com/ukraine-politics/ukrainians-most-of-all-trust-ordinary-people-volunteers-churches-and-army.html?cn-reloaded=1 (accessed on 29 January 2018).

- Koltsova, O. News Media and Power in Russia; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mickiewicz, E. Television, Power, and the Public in Russia; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedirko, T. Self-censorships in Ukraine: Distinguishing between the silences of television journalism. Eur. J. Commun. 2020, 35, 12–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlova, D. Ukrainian Media after the EuroMaidan: In Search of Independence and Professional Identity. Publizistik 2016, 61, 441–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoma, I.; Fedushko, S.; Kunch, Z. Media Manipulations in the Coverage of Events of the Ukrainian Revolution of Dignity: Historical, Linguistic, and Psychological Approaches. CEUR Workshop Proceedings. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Workshop on Control, Optimisation and Analytical Processing of Social Networks (COAPSN-2020), Lviv, Ukraine, 21 May 2020; Volume 2616, pp. 25–38. Available online: http://ceur-ws.org/Vol-2616/paper3.pdf (accessed on 3 June 2020).

- Zakharchenko, A.; Malynka, V. Methods for Determination of Internet Media Funding Models by Observing Its Content. Civitas et Lex 2016, 2, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peisakhin, L.; Arturas, R. Electoral Effects of Biased Media: Russian Television in Ukraine. Am. J. Political Sci. 2018, 62, 535–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szostek, J. The Power and Limits of Russia’s Strategic Narrative in Ukraine: The Role of Linkage. Perspect. Politics 2017, 15, 379–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sienkiewicz, M. Open Source Warfare: The Role of User-Generated Content in the Ukrainian Conflict Media Strategy. In Media and the Ukraine Crisis: Hybrid Media Practices and Narratives of Conflict; Peter Lang: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 19–70. [Google Scholar]

- Makhortykh, M.; Sydorova, M. Social Media and Visual Framing of the Conflict in Eastern Ukraine. Media War Confl. 2017, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronzhyn, A. Social Media Activism in Post-Euromaidan Ukrainian Politics and Civil Society. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference for E-Democracy and Open Government, CeDEM, Krems, Austria, 18–20 May 2016; pp. 96–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakharchenko, A. Social Actions of Social Networks Users Triggered by Media Posts Content. Soc. WELFARE Interdiscip. Approach 2019, 2, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anisimova, O.; Lukash, H.; Syerov, Y. Formation of the Image of the Specialist in Social Networks. CEUR Workshop Proceedings. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Workshop on Control, Optimisation and Analytical Processing of Social Networks (COAPSN-2020), Lviv, Ukraine, 21 May 2020; Volume 2616, pp. 39–52. Available online: http://ceur-ws.org/Vol-2616/paper4.pdf (accessed on 3 June 2020).

- Monitoring into Professional Standards in Online Media. 1st Wave in 2020 | Institute Mass Information. Institute of Mass Information. Available online: https://imi.org.ua/en/monitorings/monitoring-into-professional-standards-in-online-media-1st-wave-in-2020-i31706 (accessed on 13 February 2020).

- Zakharchenko, A.; Maksimtsova, Y.; Iurchenko, V.; Shevchenko, V.; Fedushko, S. Under the Conditions of Non-Agenda Ownership: Social Media Users in the 2019 Ukrainian Presidential Elections Campaign. In Proceedings of the International Workshop on Control, Optimisation and Analytical Processing of Social Networks (COAPSN-2019), Lviv, Ukraine, 16–17 May 2019; pp. 199–219. Available online: http://ceur-ws.org/Vol-2392/paper15.pdf (accessed on 29 June 2019).

| Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

By Artem Zakharchenko 1,Tomáš Peráček 2,Solomiia Fedushko 3,*,Yuriy Syerov 3 and Olha Trach 3, for MDPI

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open-access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).