Social media are dominant drivers in the spread of diverse narratives. The importance of marketing, algorithms, epistemic loops, and the impetus to participate digitally, through user‐generated content, liking, and sharing, is shown in the ways they influence news value, politics and democracy. Was this the case in Ukraine in the pre-election period of 2019?

The following research project was pitched by StopFake’s Maria Zhdanova for the Digital Methods Winter School 2019. It was carried in the University of Amsterdam by a team of researchers, including Elena Aversa, Franziska Martini, Mariia Zhdanova, Rasa Kasperiene, Rémy Baurichter, Sander Salvet, Luisa Zap, Maria Naum and Zhen Ye under the supervision of professor Richard Rogers. With the permission from DMI we are republishing this report, with edits conducted by Maria Zhdanova specially for stopfake.org.

NOTE: In June 2019, Facebook has banned Graph.tips and other tools that were used to search and scrape information for the research, making further investigation impossible.

As part of the Winter School data sprint, the research team looked into the extent to which disinformation has penetrated popular discourse on Facebook by analysing how posts from specific pages mention Ukrainian elections in English, Russian and Ukrainian language. The research focus on the 6 months period (July 2018 – January 2019) prior to the start of the presidential elections campaign in Ukraine and provides a starting point for a further research which is carried on by StopFake’s team throughout the 2019 – a politically decisive year for Ukraine, since both presidential and parliamentary elections will be held.

The aim of the research is to assess the quality of Facebook based discussions on about Ukraine’s political sphere, determine the signs of inauthentic behaviours and define the scale of disinformation campaigns online.

Research Questions

- To what extent has the ‘post-truth regime’ taken hold in the top posts on Facebook about the Ukrainian elections within the last 6 months?

- To what extent are the leading narratives anchored in the post-truth media infrastructure?

- How is engagement achieved for spreading the post-truth content (case studies)?

Data Collection

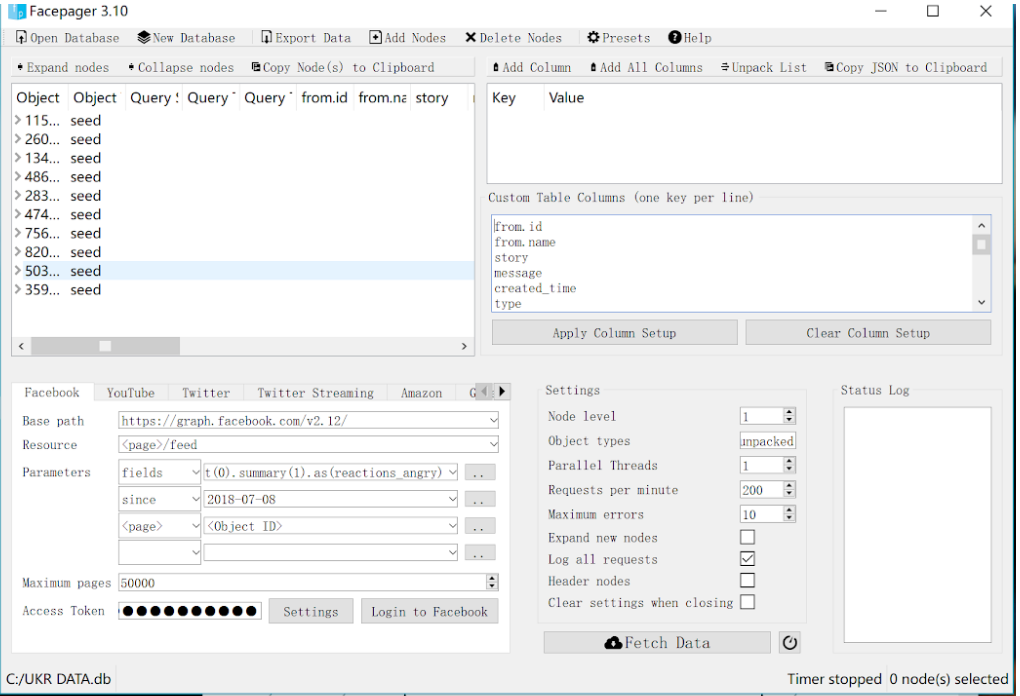

The data extraction was conducted in two steps. First, a list of relevant Facebook pages that contain the discussion of Ukraine election was created. The second step was to extract all posts from these Facebook pages using Netvizz and Facepager. We used “page posts” module within Netvizz to analyze the activities around the posts on certain pages by entering the page ID manually. However, due to a huge number of the selected Facebook pages, extracting posts from Netvizz per page becomes a limitation of effectiveness. We turned to another tool called Facepager, which “was made for fetching public available data from Facebook and other JSON-based APIs” (Jünger, 2012/2019). Similar to Netvizz, this tool allows us to add multiple Facebook IDs and extract information about the posts including page names, types of posts and other information at once.

Findings

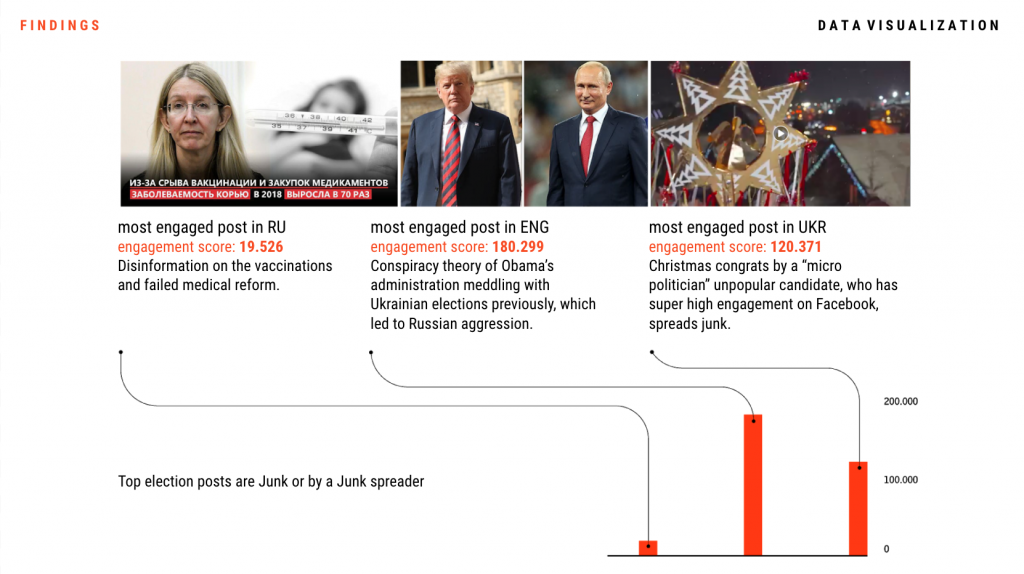

Among the 50 most engaged English Facebook posts we analyzed, 18 are posted by official media, 26 are posted by official political/organisational actors, 6 by unofficial pages such as “Russia Cybergate”, a page that mainly focuses on the Russian intervention in the U.S. presidential elections, and a page named after a fictional character Tom Joad (from John Steinbeck’s novel ‘The Grapes of Wrath’) that is critical towards the U.S. president Donald Trump. These informal and alternative media pages stand out from the others by their more emotional and visual (photos and memes) content. The most engaged post in English data has an engagement score of 180,299 and is posted by “Elbert Lee Guillory”, a former politician who distributed conspiracy theory of Obama’s administration meddling with previous Ukrainian election. The narrative generated from English pages is predominantly U.S./Russia/Ukraine relationship, while other narratives about MH17 or Russia’s aggression towards Ukraine have lower engagement scores, which means that they are not gaining as much attention as the conspiracy theory.

In the case of Top 50 posts from Ukrainian pages, generally speaking, election content on junk sites have a much higher engagement scores than on official Ukrainian media or sites. Diversified narratives can be generated from Ukrainian pages, while the dominating two is fake narratives and junk content. For instance, one of the most popular pages is “Pseudo-patriotic”. It’s using junk content not related to elections like ‘how to tie a tie’ video, to spread political methods. Sophisticated fake news, some messages criticizing Ukrainian government are not from opposition parties, but from individual micro-politicians with little affiliation with political parties. However, these micro-politicians are highly active on Facebook, using tactics such as asking people to repost in order to win something in return. Election related promotional content and holiday greetings from politicians also gathered engagements on Facebook, with the engagement scores at 28,110 and 93,720 separately.

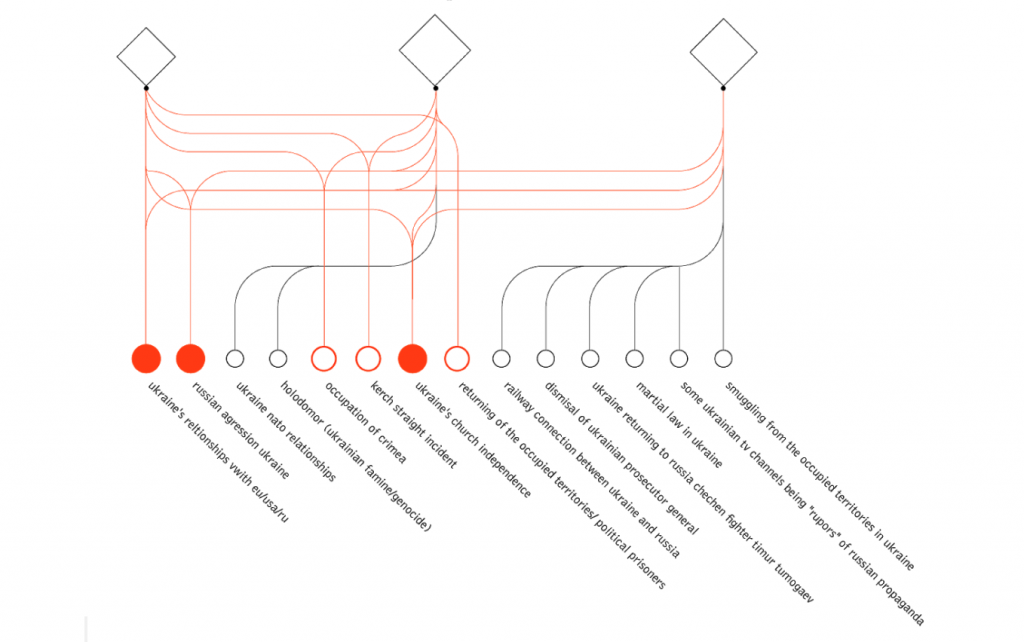

Visualization of the recurring themes in all three languages samples

By using topic modeling method we were able to identify the most popular themes that occured in all three samples. We identified three narratives that were highly discussed in Ukrainian, Russian and English language groups together. The first one included different aspect of Ukraine’s relationships with the EU, US and Russia. The second concerned Russian aggression, while the last one was focused on the independence of Ukrainian Orthodox Church.

Overall the research has shown that in each of our examined languages, the posts with the highest engagement score mostly spread unreliable content – a conspiracy theory in the English language, disinformation in the post written in Russian, and a fake narrative in the Ukrainian language. The most apparent finding when comparing the languages was that Ukrainian and Russian posts generally do not link to any sources whereas English Facebook pages predominantly use reliable news sources to reference their posts.

Read also:

- Analisys of the Russian Information Manipulation DSet Storm-1516

- 3rd EEAS Report on Foreign Information Manipulation and Interference Threats

- Disinformation Resilience Index in Central and Eastern Europe in 2024

- Sanctioned but Thriving: How Online Platforms Fail To Address the Widespread Presence of Entities Under EU Sanction