By Sarah Hurst (@XSovietNews)

In Turkey, where an estimated 245 journalists are behind bars and news is dominated by a mix of President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s propaganda and conspiracy theories, it would seem pointless for Russia to spread its own false narratives. But a RAND Corporation report on Russian media in Turkey describes the lengths Russia has gone to in Turkey, and also how Russia’s stance changed dramatically from accusing Erdogan of collaborating with ISIS to boosting his anti-Western message.

In “Russia’s Use of Media and Information Operations in Turkey: Implications for the United States,” Katherine Costello expertly dissects Russia’s activities, motives and goals. Russia has been using the techniques of “Amplification of genuine uncertainty,” “Opportunistic fabrications” and “Multiple contradictory narratives,” according to Costello, which matches with what other analysts have said about Russia’s media and social media operations all over the world.

Costello focuses on Russian reactions to three major incidents: Turkey’s shooting down of a Russian military aircraft in November 2015; the July 2016 coup attempt in Turkey; and the December 2016 assassination of the Russian ambassador in Ankara. Russian policy towards Turkey reversed itself after Erdogan apologised for the shooting down of the Russian jet in June 2016. A fragile alliance has held together since then, despite the assassination of the ambassador, and it is only now starting to fray because of the possibility of a full-scale Russian assault on Syria’s Idlib, which Turkey opposes.

ISIS accusations

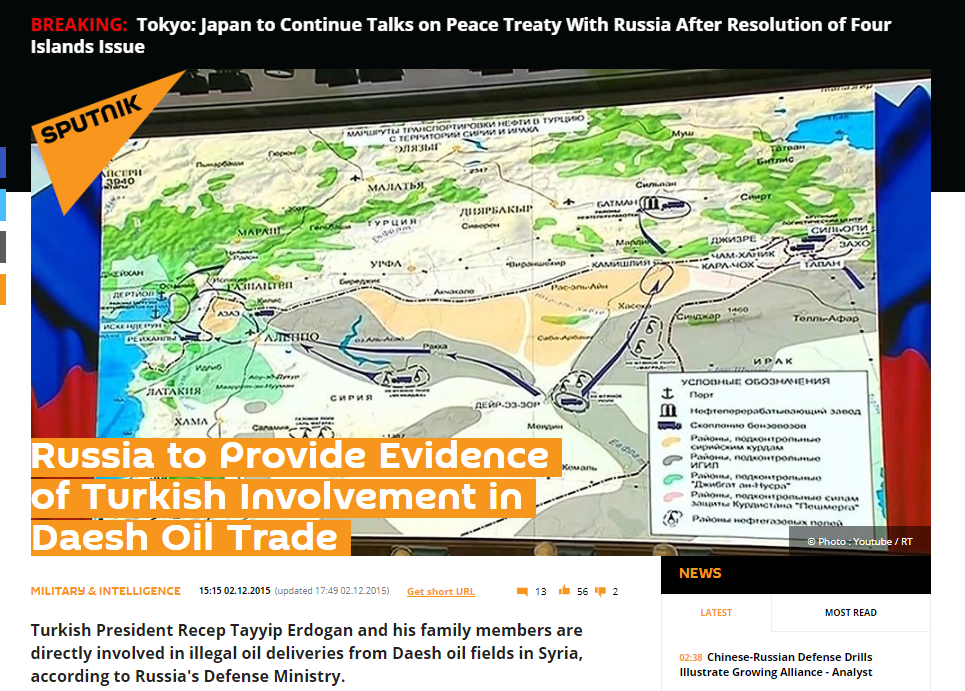

After Turkey shot down the Russian jet, Russian outlets spread claims that Erdogan and his family were buying oil from ISIS. “Russian television programs on state channel Rossiya 1 emphasized the theme that Turkish deceit and sponsorship of terrorism disgraced both Turkey and the NATO alliance as a whole,” Costello writes. Even Turkish fruit and vegetables were attacked as dangerous by Russian state media, and Russian authorities imposed a ban on them.

In December 2015 Turkish-language Sputnik ran an article with the title “Russia: Erdogan and His Family Directly Involved in ISIS’s Illegal Oil Shipment in Syria,” Costello notes. The article covered a Russian Defence Ministry briefing by then-Deputy Defence Minister Anatoly Antonov – who is now the Russian ambassador to the United States. The briefing included videos of Turkish trucks travelling across the borders with Iraq and Syria, and depicting Russian air strikes that allegedly disrupted ISIS’s oil trade. Antonov was quoted as saying “Our goal is not for Erdogan to resign, that is for the Russian people to decide,” and “Russian journalists are brave enough to tell the truth about Turkey’s crimes.” “Nevertheless, neither the article nor the video provided any actual evidence of Erdogan’s family being involved in illegal oil trade with ISIS,” Costello adds.

Some Western media outlets helped Russia by spreading its claims uncritically, according to Costello. While the New Yorker called the ISIS oil smuggling stories “nebulous”, the BBC’s bland style of reporting on the Russian claims gave them further publicity. Ukrainians also have accused the BBC of using terminology that comes straight from Russia – calling Russia’s invasion of Donbass a “civil war”, talking about a “Ukraine crisis,” and referring to Russia’s troops and mercenaries in Donbass as Ukrainian “rebels” and “separatists”. Kremlin spokespeople also frequently appear on the BBC to give Russia’s point of view on a wide range of events, no matter whether there is any truth to it or not. Recently the BBC had to admit that it had been doing the same on the issue of climate change, and issued an instruction to journalists telling them that reports on the devastating effects of climate change do not have to be “balanced” by climate change deniers. A similar problem can be seen with Brexit coverage.

Gülenists and the CIA

The attempted coup in Turkey took place just one month after Erdogan’s apology to Putin, which had drastically improved relations between Turkey and Russia. There were no more accusations about buying oil from ISIS. The story of the coup itself is highly questionable: Erdogan used it as an excuse to round up tens of thousands of people he claimed were “Gülenists” – followers of exiled preacher Fethullah Gülen – and to expand his powers in a referendum, and it can’t be ruled out that Erdogan himself staged the coup. Erdogan also intensified his anti-Western rhetoric, and Russian media simply joined in with that.

“Russian media disseminated conspiracy theories alleging US involvement in Turkey’s coup attempt. These conspiracy theories also suggested that the coup may have been related to a desire to undermine Turkish-Russian reconciliation,” Costello writes. She gives the example of an article published on the Moscow-based website Oriental Review that falsely claimed to have been authored by Arthur Hughes, a former US ambassador to Yemen. The article was later removed, but it inspired a piece in a Turkish pro-government newspaper with the headline “The Patriarchate-CIA-Gülen Alliance.” The attempt to associate Istanbul-based Patriarch Bartholomew with the coup is also interesting in the light of Russia’s current rift with Bartholomew over his recognition of the Ukrainian Church’s split with the Russian Orthodox Church. Russia can be expected to continue its efforts to spread negative stories about Bartholomew for the foreseeable future.

A second coup-related example given by Costello was an August 2016 article in the Moscow-based website New Eastern Outlook which falsely reported that the late former US National Security Adviser Zbigniew Brzezinski had acknowledged US backing of the coup attempt. Costello describes the article’s author, F. William Engdahl, as “a frequent RT commentator and anti-US conspiracy theorist.” The website listed his academic and professional qualifications below the article “as if to suggest the credibility of the article’s content and to resemble the format of legitimate commentary columns.”

Multiple narratives

Soon after the failed coup, Russian media also spread disinformation that thousands of Turkish forces were surrounding Incirlik Air Base amid rumours of a second coup attempt. The forces were actually working to secure the area for a visit by Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General Joseph Dunford. Stories on RT and Sputnik with “panic-inducing” headlines were “picked up by a popular online aggregator of breaking news and prompted an hours-long storm of activity from a small, vocal circle of users,” analysts noted later. “Russian objectives may have included provoking both Turkish and Western anxiety. Other aims may have included sowing general confusion and distrust in the post-coup environment,” Costello writes.

Turkish-Russian relations could have suffered a heavy blow in December 2016 with the assassination of the Russian ambassador, but the Kremlin didn’t want to lose Erdogan and its propaganda machine swung into action with multiple narratives blaming Gülenists, Islamic terrorists and the West. Contradictions are not necessarily detrimental to the persuasive ability of propaganda, Costello notes. As a previous RAND report, “The Russian ‘Firehose of Falsehood’ Propaganda Model” stated, “When a source appears to have considered different perspectives, consumer attitudinal confidence is greater.”

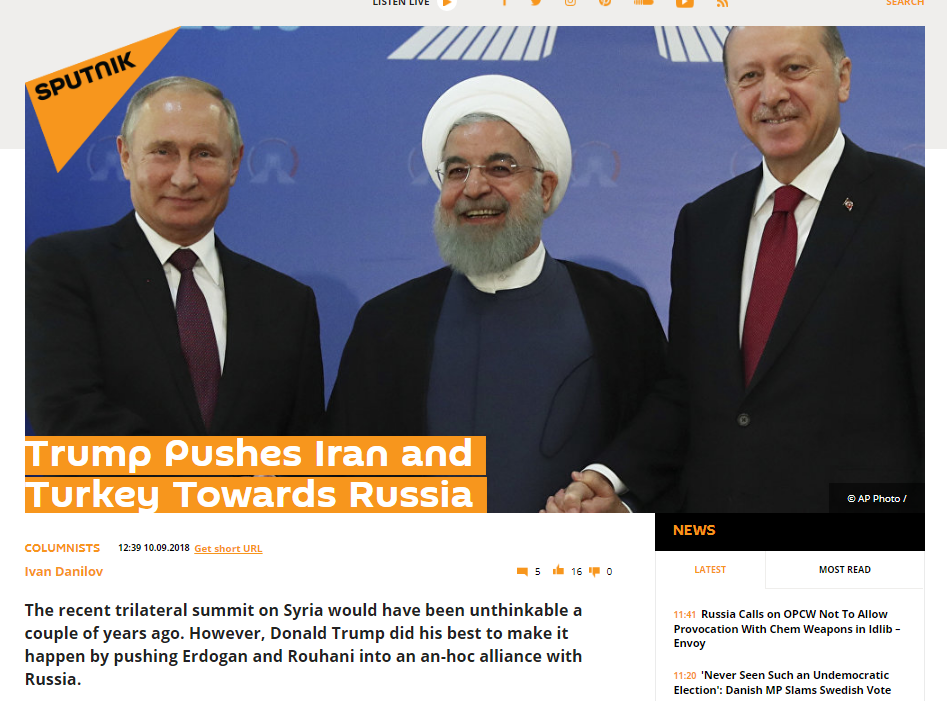

Today Turkey is intentionally moving away from its NATO partners, while Russia offers encouragement. As Costello points out, “trends in Turkish media itself are potentially as concerning as the Russian efforts… The Turkish government is also developing its own propaganda arm, TRT World.” TRT World resembles RT in a number of respects, Costello says, and Russia’s TASS is also exchanging information and photos with Turkish official news agency Anadolu. Getting facts heard above the din of this growing propaganda alliance will be a challenge – even without considering the impact of Iran, the third party power-broking in Syria with Russia and Turkey.

All three will continue trying to expand their geopolitical influence to compensate for severe domestic economic problems. Media is one of the key fronts in that battle.

By Sarah Hurst (@XSovietNews)