By Sarah Hurst (@XSovietNews), for StopFake

Russian state witnesses used ad hominem attacks and whataboutism – standard tactics by Vladimir Putin’s regime – in a failed attempt to achieve the extradition of Russian businessman Alexander Shapovalov from Scotland. Instead, the sheriff overseeing the case accepted volumes of well-researched evidence from two highly-respected British experts on human rights cases in Russia. He also gave a devastating account of how Russia’s justice system is a sham dependent on politically-motivated decisions and a ruthless FSB that “raids” successful companies.

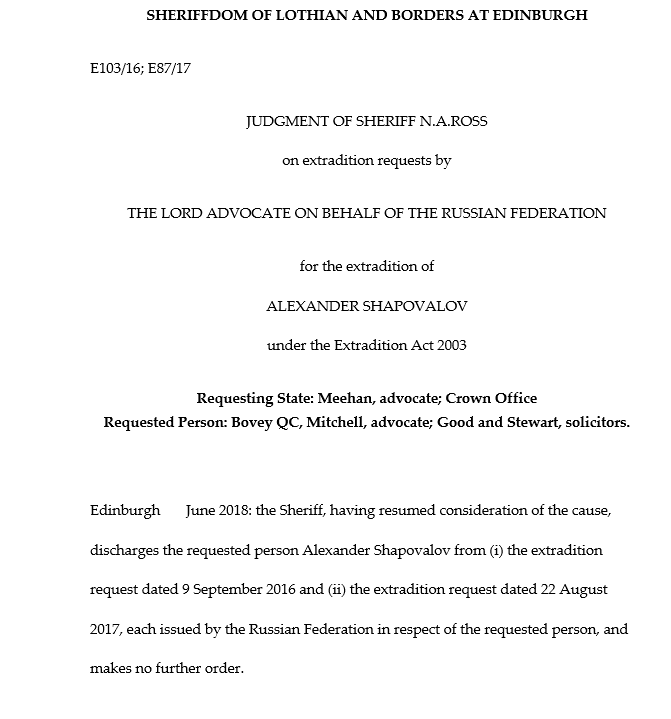

Scottish Sheriff Nigel Ross has refused to extradite 58-year-old Russian businessman Alexander Shapovalov, issuing a decision that is scathing about Russia’s justice system and brutal prisons. Shapovalov fled to Scotland shortly before the end of his trial for fraud in Russia, where he was sentenced to 10 years in prison in August 2015. The amount of the alleged fraud was about £40,663. He had spent two years under house arrest. Shapovalov lives with his partner, Regina Imamutdinova, and their two children aged six and two. The younger child has Down’s Syndrome and the older one may be autistic.

“It was a feature of this case that the Russian Federation provided very little evidence, and the evidence provided was of limited assistance,” Sheriff Ross wrote in his judgment. He describes how Shapovalov’s career flourished thanks to his friendship with Vasily Shestakov and their shared enthusiasm for martial arts. Shestakov is a close friend and judo partner of Putin, and was a Russian MP for 13 years. Interestingly, he was a guest at a UK Conservative Party summer ball for rich donors in June 2013, which then-Prime Minister David Cameron attended, and tried to improve Russia’s image in the UK through the Positive Russia Foundation, now defunct.

FSB decides everything

Under Putin the FSB became “the most powerful body in Russia, and in Dr Shapovalov’s words ‘decides everything’, controlling all political and economic life and taking over economic entities and state enterprises,” the sheriff wrote. “Dr Shapovalov’s first experience of the FSB was in 2000, when he was proposed as an office holder in a large state-owned oil company. The FSB opposed him and succeeded in getting their own nominee appointed, who would run the financial affairs through the FSB,” he continued.

Shapovalov came into conflict with the FSB again after turning a failing chemical plant around. The FSB runs the state-sponsored electronic bidding system for construction contracts. “Dr. Shapovalov’s view is that this system was manipulated to ensure FSB-linked companies win the tenders,” the sheriff wrote. “Such a contractor ‘won’ the tender for the construction of new buildings. It demanded thirty per cent payment in advance, and then demanded the remaining seventy per cent prior to completion, despite the project being unfinished.”

After Shapovalov refused payment to the FSB-linked contractor, police arrived at his door to investigate a complaint against him, but found nothing wrong. Subsequently the FSB brought the fraud charges against Shapovalov. He was held in a two-person cell for 36 hours “with a notorious robber from Central Asia” before being sent into house arrest in his flat, banned from making contact with the outside world and placed under surveillance. After fleeing to Scotland, Shapovalov spent six months in Saughton Prison.

Shapovalov “was clear in his view that his trial verdict was pre-determined,” the sheriff wrote. “He was also given a chance at an early stage to pay a bribe to a judge, but refused as he had not committed any offence. During his trial there were 36 witnesses against him, but all the evidence was poor quality, with no evidence of intention, or gain, or conspiracy. The main witnesses did not appear, but signed similar statements.”

Dire conditions in Russia

If Shapovalov were to be extradited to Russia, his partner Imamutdinova would have difficulty living in Scotland, unable to drive, but could not return to Russia with their youngest child “because Down’s children are very poorly treated,” the sheriff wrote. “She thought not a single Downs person was employed in Russia. Eighty percent of families reject a Downs child after birth, and these children ‘don’t survive’. In the UK, he would get an education and probably a job. In Russia he would face discrimination and would have no prospects for education or employment. Disabled people are not seen on the streets.”

The sheriff praised a 94-page report with 115 annexed documents and two supporting volumes of materials prepared by Bill Bowring, a professor of law at Birkbeck College, University of London, who is also a barrister and expert on human rights in Russia. Bowring’s evidence in court was taken over two days. The sheriff said he considered it “credible and reliable”. According to Bowring, the Russian state abuses the legal system in two ways, prosecutions to order and corporate raiding. “These are assisted by the lack of independence of the judiciary, the excessive influence of the state, in the form of the FSB, in judicial, police, prosecutorial, commercial, political and other areas, and oppressive penal conditions,” the sheriff wrote. “This is set against the traditional Russian view that the courts are not primarily an instrument for individual justice, but rather an instrument for educating the population.” He added that there is “a culture of ‘telephone justice’, when a judge will receive a verbal instruction from a senior colleague, or political figure, as to how to decide a case.”

The laws on fraud in Russia are so vague that any receipt of profit or transfer of ownership can be investigated as a crime, the sheriff said. Nearly all trials in Russia result in a conviction. There were 240,065 economic prosecutions in Russia in 2016, the majority of which were started for the purpose of corporate raiding, which is “no more than organised crime using the weapon and cover of the law,” the sheriff wrote. Examining a large number of news stories about abuse of the legal system in Russia and the murder of Putin critics, the sheriff said, “I accept that all of these sources create a bleak picture of a consistent and increasing refusal by the Russian state to observe either its international obligations, or its domestic obligations toward its own people and the rule of law.”

Judith Pallot, a professor emeritus at the University of Oxford, who has been researching Russian prisons since 2005, gave evidence on the conditions of detention in Russia. The sheriff described her evidence as “authoritative and accurate”. He commented: “The prison system in 1991 was acknowledged as the most inhumane, along with that of Nazi Germany, in the 20th century. The FSIN [Federal Penitentiary Service] has stated that it is committed to modernisation, but has failed to invest sufficiently or bring about a change of culture… The whole thrust of Prof Pallot’s opinion is that the problems are systemic and structural. She could ‘safely say’ that anyone in any penal colony within Russia will suffer inhumane and degrading treatment.”

Russian case inadequate

Russia submitted two written reports to support its case for the extradition of Shapovalov. One was from Sergei Gorlenko, assistant to the prosecutor-general. It called Bowring biased because of his human rights cases and said he had been campaigning to defame the Russian judicial system. “The letter does not address the alleged systemic problems at all,” the sheriff commented. “The tenor of the letter is to rely on the formal legal protections afforded to an accused. These by themselves might be acceptable. It does not, however, provide any reassurance for the point that these legal protections are, in practice, ignored or circumvented,” he added.

The other report was from Alexander Khaliulin, a professor at the Academy of the Prosecutor-General’s Office. Khaliulin referred to Shapovalov’s “negative moral qualities” and called one of Bowring’s arguments “amusing”. “In dismissing Prof Bowring’s conclusions, it relies on corruption being in all countries, not just Russia and the inappropriateness of reference to other cases,” the sheriff wrote. “The report amounts to a judgment both on Prof Bowring’s evidence and on Mr Shapovalov, rather than a source of positive evidence to allow this court to make favourable findings.” The sheriff added that he was not able to accept the report as a source of independent, fair or informative evidence.

A formal request by the court to allow live evidence by video link of Gorlenko or Khaliulin was ignored, and representatives of the Russian consulate failed to show up at scheduled meetings about Shapovalov’s case. The lack of cooperation by the Russian side coincided with the deterioration in UK-Russia relations after the poisoning of Sergei and Yulia Skripal, the sheriff said. “The evidence for the Russian Federation was poor quality, inadequate and misdirected, and I reject it as any reliable source of information,” he concluded.

The sheriff rejected the extradition request on the grounds that Shapovalov did not have the right to a fair trial, the extradition process was being abused by Russia because they prosecuted him without sufficient evidence, and he would be subjected to torture or inhuman or degrading treatment if sent to prison in Russia. If Shapovalov’s partner and their children had to return to Russia their human rights would also be breached, the sheriff said. Even if they remained in the UK, the loss of one parent would severely diminish the quality of the children’s care.

Hope for others

Commenting on the judgment to Stop Fake, Bill Bowring said, “It isn’t binding, and is in the Scottish jurisdiction – I think the first extradition case to be heard in Scotland. In fact, since 2003 when I first aced as an expert in Chechen War and YUKOS-related extradition requests by Russia, there have been quite a number of very hard-hitting judgments in the London magistrates court against Russia. Indeed, Russia has succeeded in securing the extradition of very few of the people it has requested. But this is a very pithy judgment! For which I take some credit – as does Prof Judith Pallot.”

The sheriff’s assessment of prison conditions in Russia contradicts that of a judgement in an asylum claim from 2015 seen by Stop Fake. A Russian businessman in the UK who feared being sent back to prison in Russia had his claim rejected, and was told: “Whilst this evidence does not paint the Russian Federation’s prison system or conditions in a good light, it is noted that the authorities are doing all they can to make them better, also the conditions and treatment are not evident in all institutions nor are they experienced by all prisoners… As it is not considered that the prison conditions in the Russian Federation would breach your rights under Articles 2 or 3 of the Immigration rules you do not qualify for Humanitarian Protection.”

Whether more UK judges and Home Office officials will in future agree with the Scottish sheriff or the earlier ruling remains to be seen. But now at least, any Russian fearing prosecution in the UK can refer to the evidence submitted in Shapovalov’s case and the sheriff’s indictment of the Russian system, and they may have a far stronger case. Russia might want to think about taking British justice more seriously. Their lies don’t work in our courts.

By Sarah Hurst (@XSovietNews), for StopFake